You’ve built a microservice that saves orders to a database and publishes events to Kafka. Everything works great—until Kafka goes down for five minutes. Now you have orders in your database but no events published. Your downstream services never learn about these orders. You have inconsistent state.

This is the dual-write problem, and the Transactional Outbox pattern solves it elegantly. Chris Richardson documented this pattern in his Microservices.io pattern catalog, and it’s become a foundational technique for reliable event-driven systems.

A Pattern I’ve Encountered Throughout My Career

Before we dive into implementation, I want to share how I’ve encountered variations of this pattern throughout my career—often before it had a formal name.

Early 2000s: Oracle AQ and Stored Procedures

Early in my career, I worked on projects that needed to track usage data. The process involved opening a ticket to have a DBA write a stored procedure that would insert XML into a database table. On the server side, we’d insert tracking data into this table, and then database triggers would fire events to Oracle Advanced Queuing (AQ) for downstream processing. We didn’t call it an “outbox”—it was just “the tracking table”—but it was exactly this pattern: write to a table atomically with business data, then a separate mechanism handles delivery.

The RabbitMQ Incident: Learning the Hard Way

Later, while building a system that ingested webhooks from third-party services, we published directly to RabbitMQ. It worked great until RabbitMQ went down during a traffic spike. We lost webhooks—events that our partners expected us to process. The fix? We built a simple journal on the HTTP ingestion servers that persisted incoming webhooks to local SQLite files, then a background process that would read the journal and push records to RabbitMQ once it recovered. Classic outbox, implemented under pressure at 2 AM.

RabbitMQ Sidecars

On another project, each web service ran a RabbitMQ “sidecar”—a local broker instance that shoveled messages to a central broker. The application wrote to the local broker (fast, always available), and the shovel handled the unreliable network to the central cluster. This is essentially an outbox where the “table” is a local message queue.

CDC to Kafka

More recently, I’ve worked on systems where synchronous REST APIs buffer events to a database table, and Debezium’s Change Data Capture streams those changes to Kafka. The API returns success as soon as the database write commits—no waiting for Kafka. The CDC pipeline handles eventual delivery with exactly-once semantics.

The point is: this pattern keeps showing up because the dual-write problem is fundamental. Whether it’s Oracle AQ triggers, local journals, sidecar brokers, or CDC pipelines, the solution is always the same: make the write atomic and local, then handle delivery asynchronously.

The Dual-Write Problem

Here’s the naive approach to publishing events:

async def create_order(order: Order):

# Step 1: Save to database

await db.execute(

"INSERT INTO orders (id, customer_id, total) VALUES ($1, $2, $3)",

order.id, order.customer_id, order.total

)

# Step 2: Publish event

await kafka.publish("orders.created", OrderCreated(order_id=order.id, ...))

return order

What could go wrong?

- Kafka fails after DB commit: Order saved, but event never published

- Service crashes between steps: Same result

- Kafka succeeds, DB fails on commit: Event published for non-existent order

- Network partition: Timeouts, retries, duplicates

You can’t make both operations atomic without distributed transactions (2PC), which are slow and complex. The outbox pattern sidesteps this entirely.

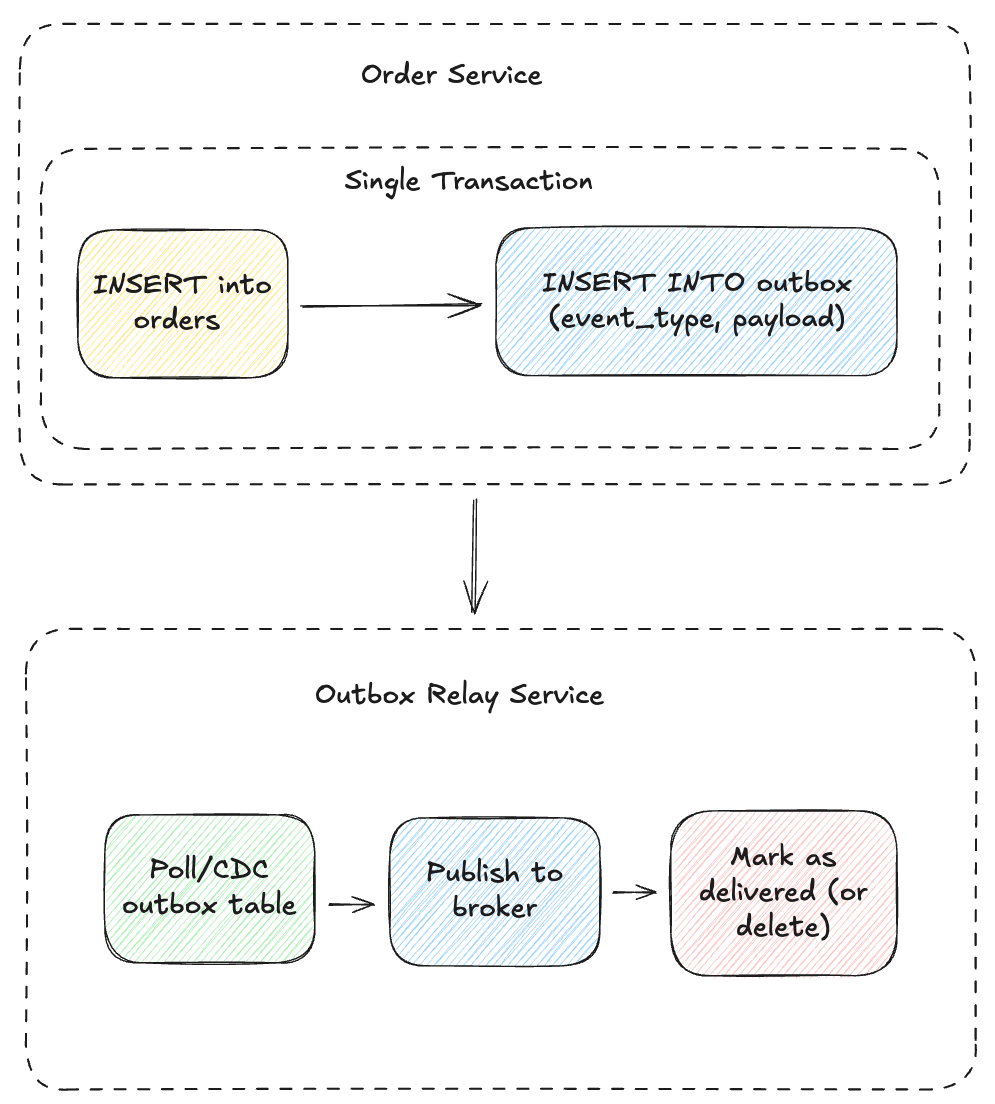

The Transactional Outbox Pattern

Instead of publishing to Kafka directly, write the event to an outbox table in the same database transaction as your business data:

Now your code looks like:

async def create_order(order: Order):

async with db.transaction():

# Save order

await db.execute(

"INSERT INTO orders (id, customer_id, total) VALUES ($1, $2, $3)",

order.id, order.customer_id, order.total

)

# Save event to outbox (same transaction!)

await db.execute(

"""INSERT INTO outbox (id, event_type, topic, payload, created_at)

VALUES ($1, $2, $3, $4, NOW())""",

uuid4(), "OrderCreated", "orders.created",

json.dumps({"order_id": order.id, "customer_id": order.customer_id, ...})

)

return order

Either both writes succeed, or neither does. Database ACID guarantees handle the atomicity. This is just a very naive example, there are many different ways one could implement this approach.

The Outbox Table

A typical outbox table can be designed however you see fit, but the basic example below to capture all of the details and be flexible for kafka specific features.

CREATE TABLE outbox (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

sequence_id BIGSERIAL NOT NULL,

event_type TEXT NOT NULL,

topic TEXT NOT NULL,

partition_key TEXT,

payload JSONB NOT NULL,

headers JSONB DEFAULT '{}',

aggregate_type TEXT,

aggregate_id TEXT,

aggregate_version INT,

created_at TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT NOW(),

published_at TIMESTAMPTZ,

CONSTRAINT chk_aggregate_complete CHECK (

(aggregate_type IS NULL AND aggregate_id IS NULL) OR

(aggregate_type IS NOT NULL AND aggregate_id IS NOT NULL)

)

);

CREATE INDEX idx_outbox_unpublished ON outbox (sequence_id)

WHERE published_at IS NULL;

CREATE UNIQUE INDEX idx_outbox_aggregate_ordering

ON outbox (aggregate_type, aggregate_id, aggregate_version)

WHERE aggregate_version IS NOT NULL;

A few things worth noting:

sequence_idprovides reliable ordering for the relay. Using created_at seems intuitive but concurrent transactions can produce identical or out-of-order timestamps.partition_keyensures related events land on the same Kafka partition, preserving ordering where it matters.aggregate_type/id/versiongroups events by domain entity—useful for CDC-based approaches and for enforcing per-aggregate ordering when multiple events are written in a single transaction.published_attracks delivery status; NULL means pending. The partial index on sequence_id WHERE published_at IS NULL keeps relay polling efficient even as the table grows.

The check constraint ensures aggregate fields are used consistently—you either track the aggregate or you don’t, but not halfway.

Relay Strategies

You have two main options for the relay that publishes events from the outbox to Kafka:

1. Polling Publisher

A simple background worker that polls the outbox:

async def outbox_relay():

while True:

async with db.transaction():

# Fetch unpublished events (with lock to prevent duplicates)

events = await db.fetch(

"""SELECT * FROM outbox

WHERE published_at IS NULL

ORDER BY created_at

LIMIT 100

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED"""

)

for event in events:

try:

await kafka.publish(

topic=event["topic"],

key=event["partition_key"],

value=event["payload"],

headers=event["headers"],

)

# Mark as published

await db.execute(

"UPDATE outbox SET published_at = NOW() WHERE id = $1",

event["id"]

)

except Exception as e:

logger.error(f"Failed to publish event {event['id']}: {e}")

# Will retry on next poll

await asyncio.sleep(1) # Poll interval

Pros: Simple, no additional infrastructure Cons: Polling delay, database load

2. Change Data Capture (CDC)

Tools like Debezium read the database’s transaction log and stream changes to Kafka in near real-time:

# Debezium connector configuration

{

"name": "outbox-connector",

"config": {

"connector.class": "io.debezium.connector.postgresql.PostgresConnector",

"database.hostname": "postgres",

"database.port": "5432",

"database.user": "debezium",

"database.password": "secret",

"database.dbname": "orders",

"table.include.list": "public.outbox",

"transforms": "outbox",

"transforms.outbox.type": "io.debezium.transforms.outbox.EventRouter",

"transforms.outbox.table.field.event.type": "event_type",

"transforms.outbox.table.field.event.key": "aggregate_id",

"transforms.outbox.table.field.event.payload": "payload",

"transforms.outbox.route.topic.replacement": "${routedByValue}"

}

}

Debezium’s Outbox Event Router is purpose-built for this pattern.

Pros: Near real-time, no polling, lower database load Cons: Additional infrastructure (Kafka Connect, Debezium)

Handling Duplicates

The outbox guarantees at-least-once delivery, not exactly-once. If the relay publishes an event but crashes before marking it delivered, it will republish on restart. Consumers must be idempotent.

Strategies for idempotency:

1. Idempotency Key in Event

Include a unique key consumers can use for deduplication:

event = {

"event_id": str(uuid4()), # Unique per event

"idempotency_key": f"order:{order.id}:created", # Business-level key

"order_id": order.id,

...

}

Consumers track processed event_ids:

async def handle_order_created(event):

# Check if already processed

if await redis.sismember("processed_events", event["event_id"]):

logger.info(f"Skipping duplicate event {event['event_id']}")

return

# Process the event

await process_order(event)

# Mark as processed (with TTL)

await redis.sadd("processed_events", event["event_id"])

await redis.expire("processed_events", 86400 * 7) # 7 days

2. Idempotent Operations

Design operations to be naturally idempotent:

# Instead of: UPDATE inventory SET quantity = quantity - 1

# Use: UPDATE inventory SET quantity = $1 WHERE order_id = $2

# (Setting absolute value is idempotent)

# Instead of: INSERT INTO notifications (...)

# Use: INSERT INTO notifications (...) ON CONFLICT (order_id) DO NOTHING

3. Database Constraints

Use unique constraints to prevent duplicate processing:

CREATE TABLE processed_events (

event_id UUID PRIMARY KEY,

processed_at TIMESTAMPTZ DEFAULT NOW()

);

-- In consumer:

INSERT INTO processed_events (event_id) VALUES ($1)

ON CONFLICT DO NOTHING

RETURNING event_id;

-- If returns NULL, event was already processed

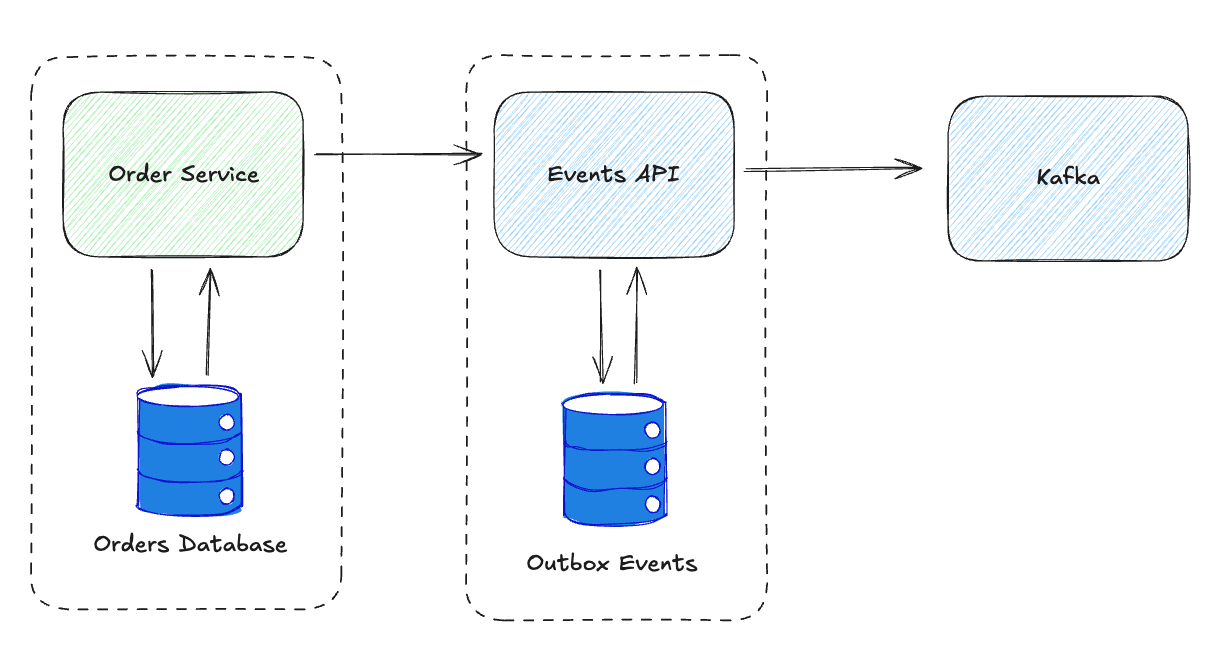

API-Based Outbox

Instead of sharing a database, some architectures expose the outbox as a centralized Events API:

The Order Service calls the Events API instead of writing to Kafka:

async def create_order(order: Order):

# Save order to local database

await db.execute("INSERT INTO orders ...")

# Submit event to centralized Events API

async with httpx.AsyncClient() as client:

response = await client.post(

"http://events-api/events",

json={

"event_type": "OrderCreated",

"topic": "orders.created",

"partition_key": order.customer_id,

"payload": {

"order_id": order.id,

"customer_id": order.customer_id,

"total": str(order.total),

},

"idempotency_key": f"order:{order.id}:created",

},

headers={"Idempotency-Key": f"order:{order.id}:created"},

)

response.raise_for_status()

The Idempotency-Key header is an emerging standard (IETF draft, widely adopted by Stripe, Increase, and others) that lets clients safely retry requests—the server deduplicates based on this key.

Wait… doesn’t this have the same dual-write problem? Yes, but the Events API can provide:

- Idempotency: Deduplicates based on

idempotency_key - Durability: Stores events before returning success

- Retries: Client can safely retry on failure

- Centralized management: One place for schemas, routing, monitoring

The trade-off is eventual consistency between order creation and event publishing. For many use cases, this is acceptable.

When to Use the Outbox Pattern

Use it when:

- You need guaranteed event delivery

- Events must be consistent with database state

- You’re already using a relational database

- Downstream services depend on your events

Skip it when:

- Events are best-effort (analytics, logging)

- You’re using an event store as your primary database

- The added complexity isn’t worth the guarantee

Implementation Checklist

Here’s what you need to implement the outbox pattern:

- Outbox table: Schema with event metadata and payload

- Application changes: Write to outbox in same transaction

- Relay mechanism: Polling worker or CDC pipeline

- Idempotency handling: In consumers or centralized

- Monitoring: Track outbox lag, failed publishes

- Cleanup: Archive or delete old published events

And on top of all of it, you will need monitoring and alerting around this just like you would any other piece of infrastructure in a production environment.

Libraries and Tools

Debezium (CDC) is the gold standard for CDC-based outbox that I have seen a few times in my career. Works with PostgreSQL, MySQL, SQL Server, MongoDB.

Most language centric implementations tend to be tailored to the environment they are deployed in so I have not seen many framework based implementations of outbox. Any of the frameworks we mentioned around enterprise integration patterns could be suitable for implementing outbox. For example, Redpanda Connect provides connectors that make implementing the relay straightforward.

Redpanda Connect: CDC Approach

Using the postgres_cdc input, changes to the outbox table are streamed in real-time via PostgreSQL’s logical replication:

input:

postgres_cdc:

dsn: "postgres://user:pass@db:5432/outbox?sslmode=disable"

schema: public

tables:

- outbox

stream_snapshot: false # Only stream new changes

temporary_slot: false

pipeline:

processors:

# Filter to only INSERT operations on outbox

- mapping: |

root = if this.operation != "insert" { deleted() }

# Transform CDC envelope to clean event

- mapping: |

root.key = this.payload.after.partition_key

root.value = {

"event_type": this.payload.after.event_type,

"payload": this.payload.after.payload.parse_json(),

"timestamp": this.payload.after.created_at,

"idempotency_key": this.payload.after.id

}

output:

kafka_franz:

seed_brokers:

- kafka:9092

topic: '${! this.payload.after.topic }'

key: '${! this.key }'

partitioner: manual

metadata:

include_patterns:

- ".*"

Redpanda Connect: Polling Approach

For simpler setups without CDC infrastructure, poll the outbox table directly:

input:

sql_select:

driver: postgres

dsn: "postgres://user:pass@db:5432/mydb?sslmode=disable"

table: outbox

columns:

- id

- event_type

- topic

- partition_key

- payload

- created_at

where: published_at IS NULL

args_mapping: ""

init_statement: ""

pipeline:

processors:

- mapping: |

root.key = this.partition_key

root.topic = this.topic

root.value = {

"event_type": this.event_type,

"payload": this.payload.parse_json(),

"timestamp": this.created_at,

"idempotency_key": this.id

}

meta outbox_id = this.id

output:

broker:

outputs:

# Publish to Kafka

- kafka_franz:

seed_brokers:

- redpanda:9092

topic: '${! this.topic }'

key: '${! this.key }'

# Mark as published

- sql_raw:

driver: postgres

dsn: "postgres://user:pass@db:5432/mydb?sslmode=disable"

query: "UPDATE outbox SET published_at = NOW() WHERE id = $1"

args_mapping: 'root = [ meta("outbox_id") ]'

The CDC approach offers lower latency and less database load, while polling is simpler to set up and debug. Both provide at-least-once delivery—your consumers must be idempotent.

Simple Reliability

This pattern works well because it has a very simple approach to and buffers well against messaging infrastructure issues. Of course, you will always have different areas to failproof, for example what happens if the table gets too large? How do you handle heavy write contention on the outbox? There’s still many reliability issues to consider with some just being an acceptable tradeoff.

Whether you use a shared database, an API, local kafka journals or whatever, the core principle is always the same: make the write atomic and local, handle delivery asynchronously. Pick the implementation that fits your infrastructure and operational capabilities.

References

Canonical Pattern Documentation:

- Microservices.io: Transactional Outbox - Chris Richardson’s definitive pattern description

- Microservices.io: Polling Publisher - The relay pattern for polling-based outbox

- Microservices.io: Transaction Log Tailing - CDC-based approach

Implementation Guides:

- Debezium: Reliable Microservices Data Exchange - Excellent deep dive

- Debezium Outbox Event Router - Production-ready CDC implementation

- Confluent: Transactional Outbox Pattern - Kafka-specific guidance

Books:

- Microservices Patterns by Chris Richardson - Chapter on managing transactions

- Designing Data-Intensive Applications by Martin Kleppmann - Background on distributed systems challenges

The outbox pattern pairs well with AsyncAPI for documenting the events that flow through your system.