Happy New Years for my APAC friends! In my previous post we traced the evolution from synchronous request-reply to enterprise event delivery platforms. We built recipient lists, webhook registrations, and bundled integrations. But we glossed over a critical question: what happens when delivery fails?

In production, failure isn’t exceptional. It’s constant. Endpoints go down. Networks partition. Rate limits trigger. Servers restart. A webhook platform that doesn’t handle failure gracefully isn’t a platform at all.

The telephone network solved these problems decades ago. When you dialed a number and got a busy signal, the network didn’t keep hammering the line. When trunk lines overloaded, calls were routed to overflow groups. When entire exchanges failed, traffic was isolated so one neighborhood’s outage didn’t take down the city.

Today we’re building the reliability layer using patterns the telecom industry perfected: retry with exponential backoff, dead letter queues, circuit breakers, bulkheads for tenant isolation, claim check for bandwidth optimization, and batching for efficiency.

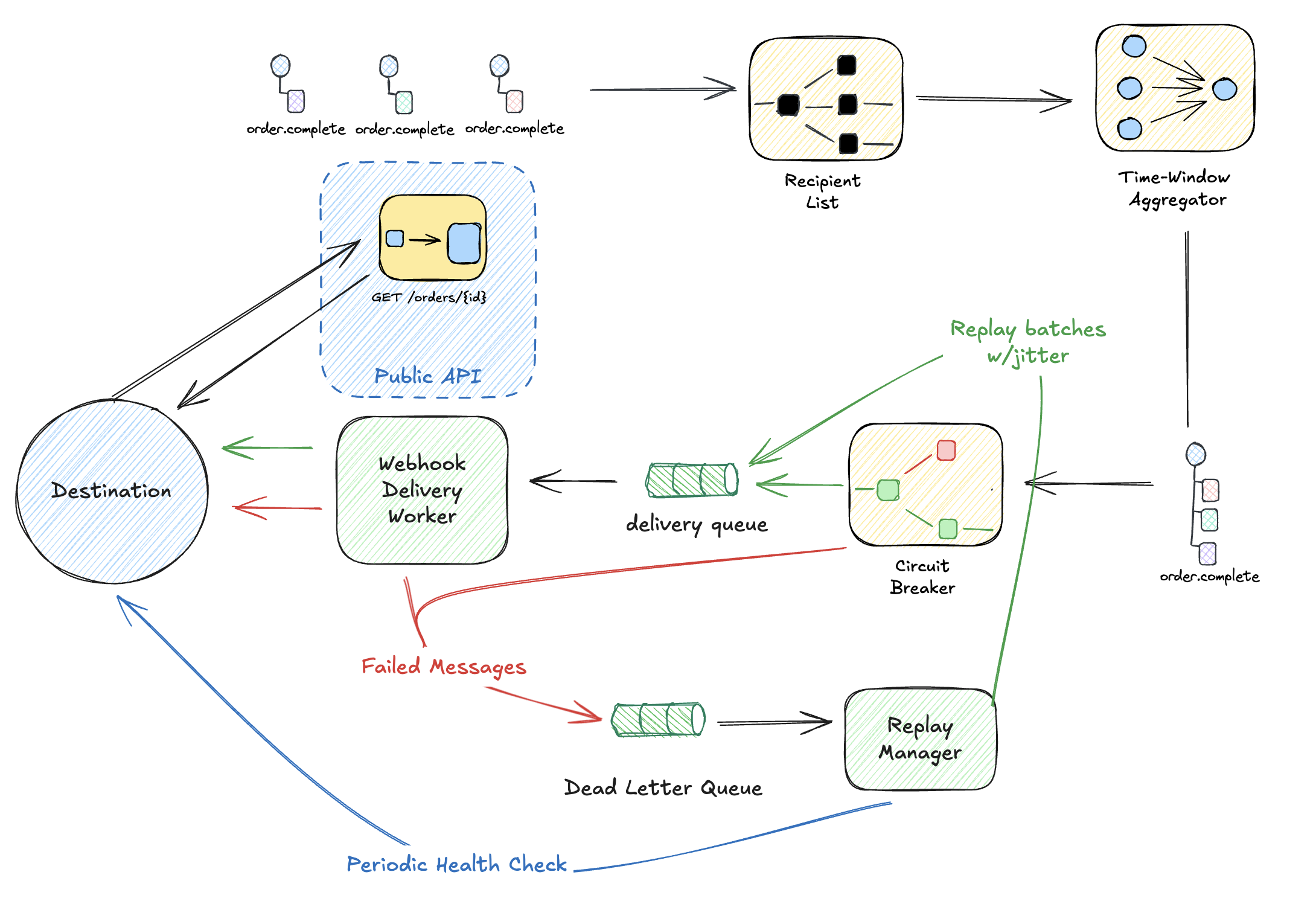

The Full Delivery Pipeline

Here’s what we’re building:

Let’s break down each component.

Retry with Exponential Backoff

Exponential backoff was popularized by Ethernet’s CSMA/CD protocol in the 1970s. When multiple devices tried to transmit simultaneously and collided, each device would wait a random time before retrying. With each collision, the maximum wait time doubled. This prevented “retry storms” from saturating the network.

When webhook delivery fails, the same principle applies. Don’t hammer the endpoint. The formula:

$$\text{delay} = \min(\text{base} \times 2^{\text{attempt}} + \text{jitter},\ \text{maxDelay})$$

Where:

- $\text{base} = 1\text{s}$

- $\text{jitter} = \text{random}(0, \frac{\text{delay}}{4})$

- $\text{maxDelay} = 300\text{s}$

This creates an exponential curve with randomized jitter to prevent thundering herd:

Attempt 1: fail → wait 1s + jitter (0-250ms)

Attempt 2: fail → wait 2s + jitter (0-500ms)

Attempt 3: fail → wait 4s + jitter (0-1s)

Attempt 4: fail → wait 8s + jitter (0-2s)

Attempt 5: fail → wait 16s + jitter (0-4s)

Attempt 6: fail → wait 32s + jitter (0-8s)

...

Attempt N: fail → wait 300s (capped)

Total time before giving up (5 retries):

$$\text{Total} = \sum_{i=0}^{4} \text{base} \times 2^i = 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + 16 = 31\text{s}$$

For ~5 minutes of retry time, use 8 attempts:

$$\sum_{i=0}^{7} 2^i = 2^8 - 1 = 255\text{s} \approx 4.25\text{ minutes}$$

Implementation Examples

For production webhook delivery, use a persistent task queue that survives restarts and crashes.

Python with Taskiq: async-native, broker-agnostic (Redis, RabbitMQ, or Postgres), with middleware for retry logic. Jobs persist to Redis immediately—restart your workers anytime without losing deliveries.

# pip install taskiq taskiq-redis httpx

from taskiq_redis import ListQueueBroker, RedisAsyncResultBackend

from taskiq import SimpleRetryMiddleware

import httpx

broker = ListQueueBroker(url="redis://localhost:6379").with_result_backend(

RedisAsyncResultBackend(redis_url="redis://localhost:6379")

).with_middlewares(

SimpleRetryMiddleware(default_retry_count=5)

)

@broker.task(retry_on_error=True)

async def deliver_webhook(url: str, payload: dict, secret: str) -> None:

async with httpx.AsyncClient() as client:

response = await client.post(url, json=payload, headers=sign(payload, secret))

# 429 = rate limited, retry after backoff

if response.status_code == 429:

response.raise_for_status()

# Other 4xx = client error, don't retry

if 400 <= response.status_code < 500:

return

response.raise_for_status() # 5xx triggers retry

# Enqueue: await deliver_webhook.kiq(url, payload, secret)

# Run worker: taskiq worker myapp.tasks:broker

Elixir with Oban: the de facto standard for background jobs in Elixir. Uses PostgreSQL for persistence with first-class support for custom backoff functions and job introspection.

# mix deps.get oban

defmodule MyApp.WebhookWorker do

use Oban.Worker, queue: :webhooks, max_attempts: 5

@impl Oban.Worker

def perform(%Oban.Job{args: %{"url" => url, "payload" => payload}}) do

case Req.post(url, json: payload, headers: sign(payload)) do

{:ok, %{status: status}} when status in 200..299 ->

:ok

{:ok, %{status: 429, headers: headers}} ->

{:snooze, parse_retry_after(headers)} # Respect Retry-After header

{:ok, %{status: status}} when status in 400..499 ->

:discard

{:ok, %{status: status}} ->

{:error, "Server error: #{status}"}

{:error, reason} ->

{:error, reason}

end

end

defp parse_retry_after(headers) do

case List.keyfind(headers, "retry-after", 0) do

{_, seconds} -> String.to_integer(seconds)

nil -> 60 # Default to 60s if no header

end

end

@impl Oban.Worker

def backoff(%Oban.Job{attempt: attempt}) do

trunc(:math.pow(2, attempt)) + :rand.uniform(5)

end

end

# Enqueue: Oban.insert(MyApp.WebhookWorker.new(%{url: url, payload: payload}))

Both examples distinguish between retryable and non-retryable errors. A 429 Too Many Requests means “slow down”—definitely retry with backoff. But a 400 Bad Request won’t succeed no matter how many times you try—don’t waste resources on it.

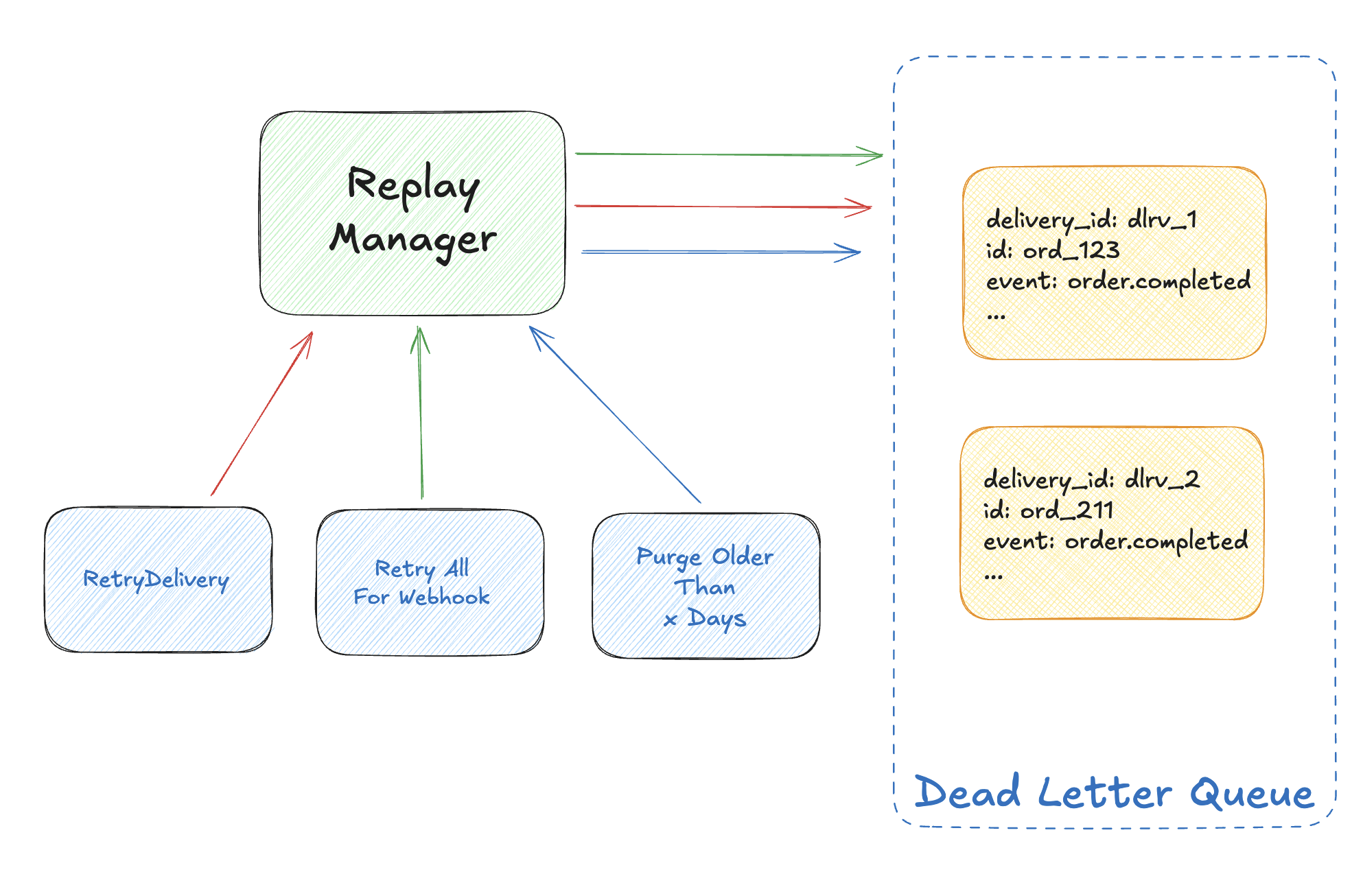

Dead Letter Queue + Command Events

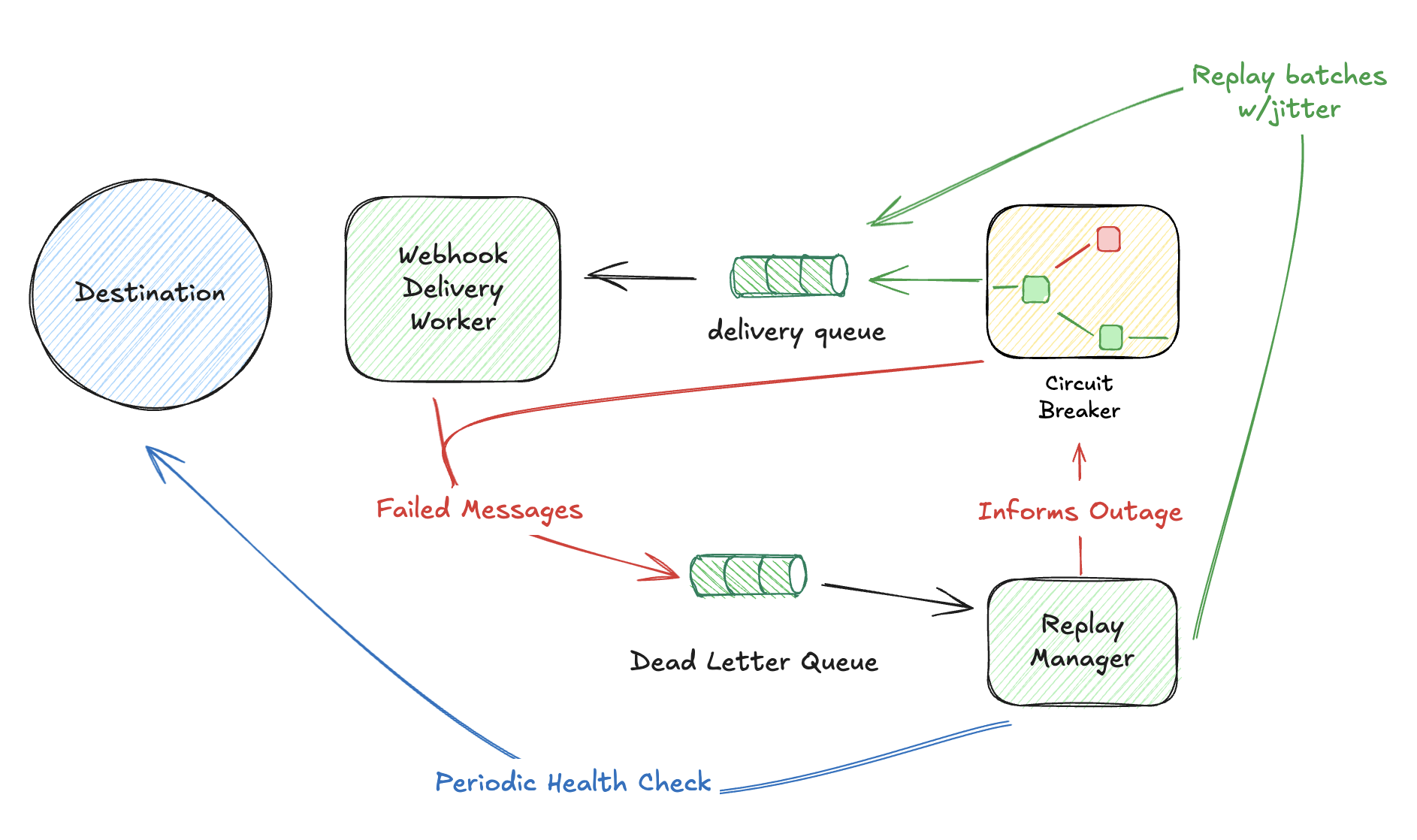

Failed deliveries don’t disappear. They land in a dead letter queue where operators can inspect and replay:

But manual replay is reactive. A sophisticated platform detects outages automatically, holds traffic during downtime, and gracefully resumes delivery when the endpoint recovers.

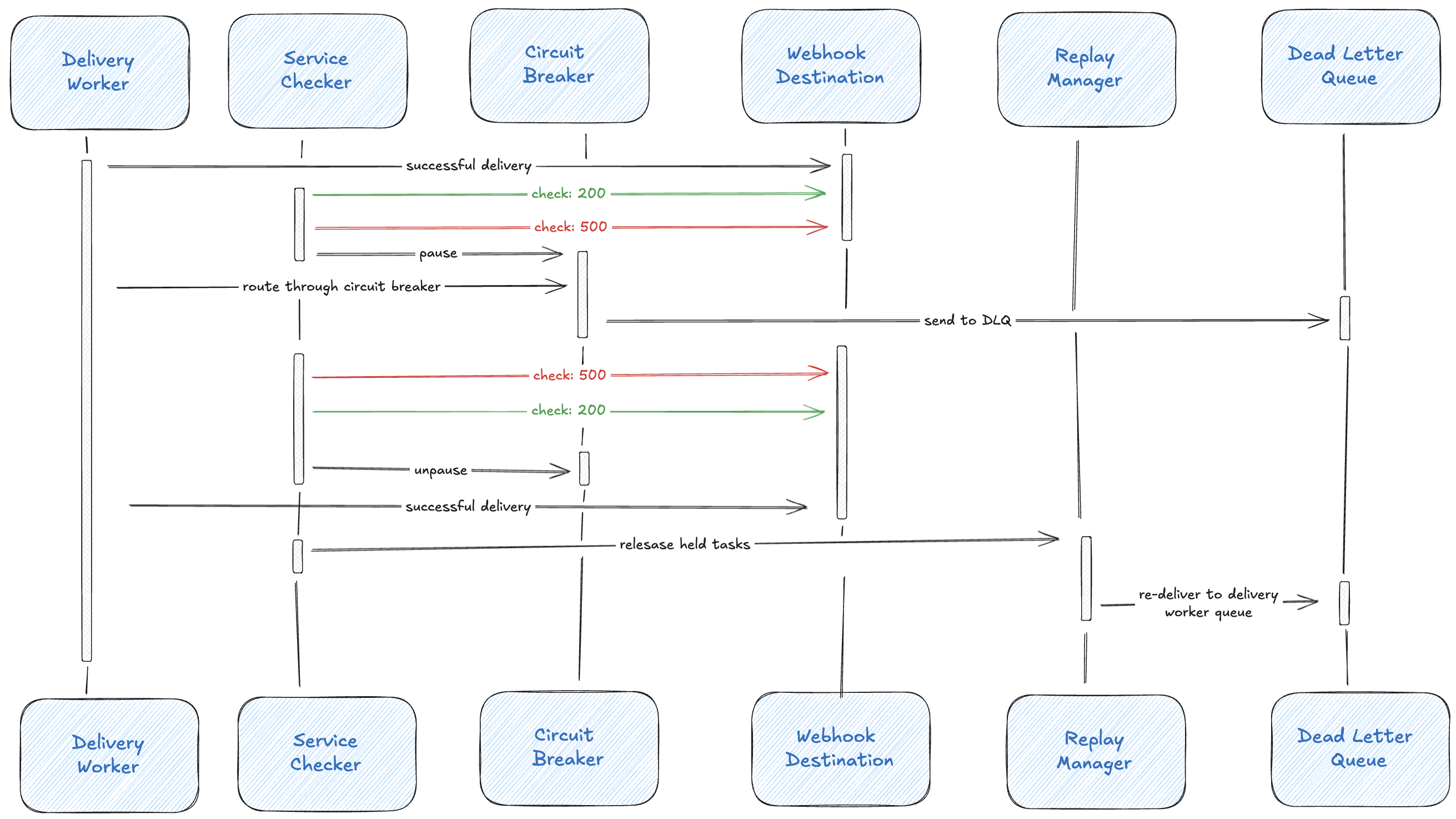

Automatic Outage Detection and Recovery

Design the system to track endpoint health continuously:

State behaviors:

HEALTHY → Normal delivery, record throughput metrics

DEGRADED → Continue delivery, increase monitoring frequency

UNHEALTHY → Shunt new messages to holding queue, start health checks

RECOVERING → Drain holding queue at ramped rates

When an endpoint becomes UNHEALTHY, new messages bypass the delivery queue entirely and go to a holding queue. This prevents wasting resources on deliveries that will fail and lets the client’s system recover without pressure.

Health Check Probing

While messages are held, the platform periodically probes the endpoint:

Health Check Schedule (exponential backoff):

Attempt 1: 30 seconds after entering UNHEALTHY

Attempt 2: 1 minute

Attempt 3: 2 minutes

Attempt 4: 5 minutes

Attempt 5: 10 minutes

...

Max interval: 30 minutes

Probe request:

HEAD /webhooks/orders HTTP/1.1

X-Webhook-Ping: health-check

Success criteria:

- 2xx response within 5 seconds

- Optional: verify response includes expected header

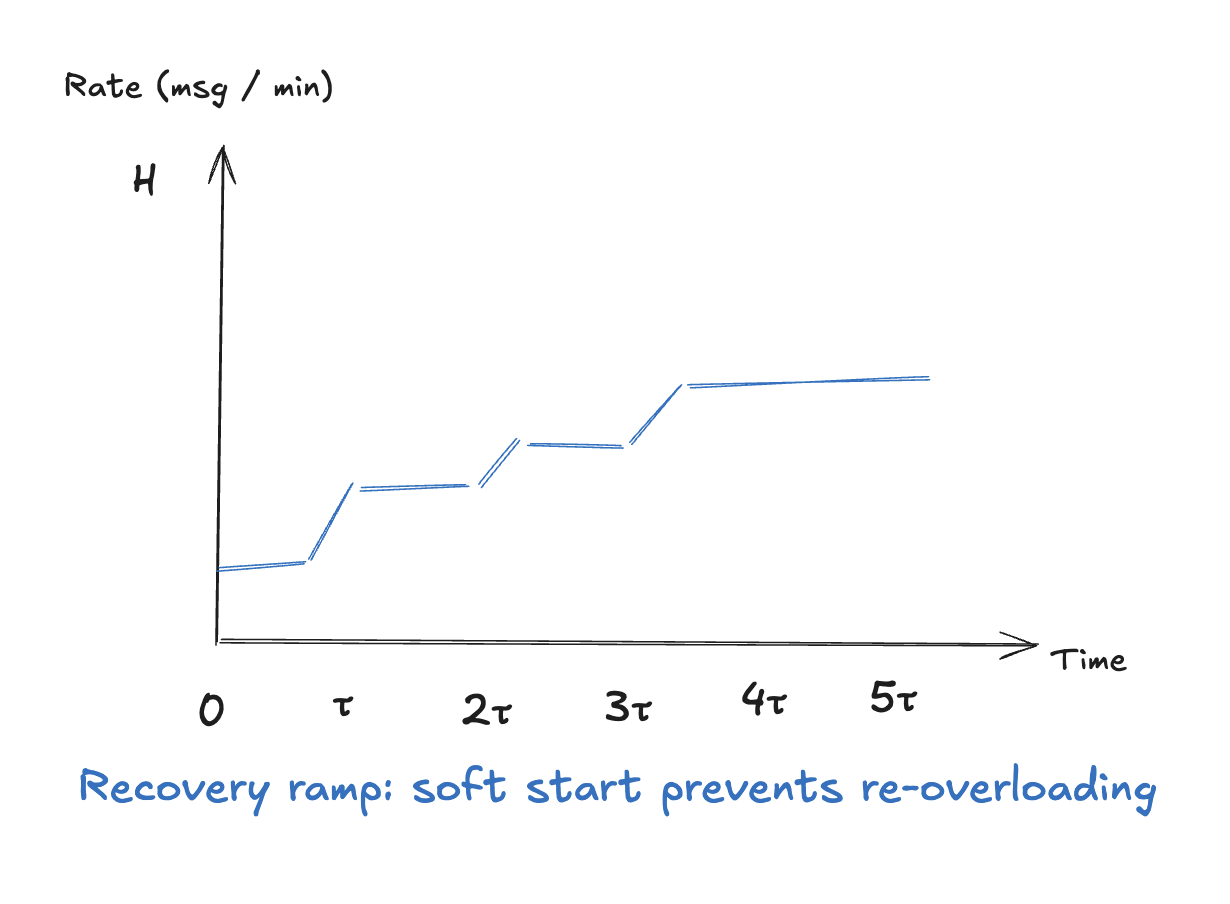

Gradual Recovery with Rate Ramping

Here’s the critical insight: when an endpoint recovers after an outage, you can’t immediately dump 10,000 held messages at it. The sudden traffic spike might knock it down again. Instead, ramp up delivery rate gradually based on the endpoint’s historical capacity.

Recovery rate formula:

Let H = historical average throughput (msg/min)

Let t = time since recovery started (minutes)

Let τ = ramp time constant (e.g., 5 minutes)

Rate(t) = H × (1 - e^{-t/τ})

This produces an exponential ramp from 0 to H:

t=0: Rate = 0% of historical

t=τ: Rate = 63% of historical

t=2τ: Rate = 86% of historical

t=3τ: Rate = 95% of historical

t=5τ: Rate ≈ 99% of historical (effectively full speed)

Visualized:

Example: If an endpoint historically handled 50 msg/min before the outage:

| Time | Rate | Delivered |

|---|---|---|

| t=0 | 0 msg/min | Health check passes, begin recovery |

| t=1 min | 9 msg/min | ~9 messages released |

| t=2 min | 16 msg/min | ~25 cumulative |

| t=5 min | 32 msg/min | ~100 cumulative |

| t=10 min | 43 msg/min | ~300 cumulative |

| t=15 min | 48 msg/min | ~500 cumulative |

| t=20 min | 50 msg/min | Full speed, holding queue draining |

If the endpoint starts failing again during recovery, immediately return to UNHEALTHY state and pause the drain. The next recovery attempt will be more conservative.

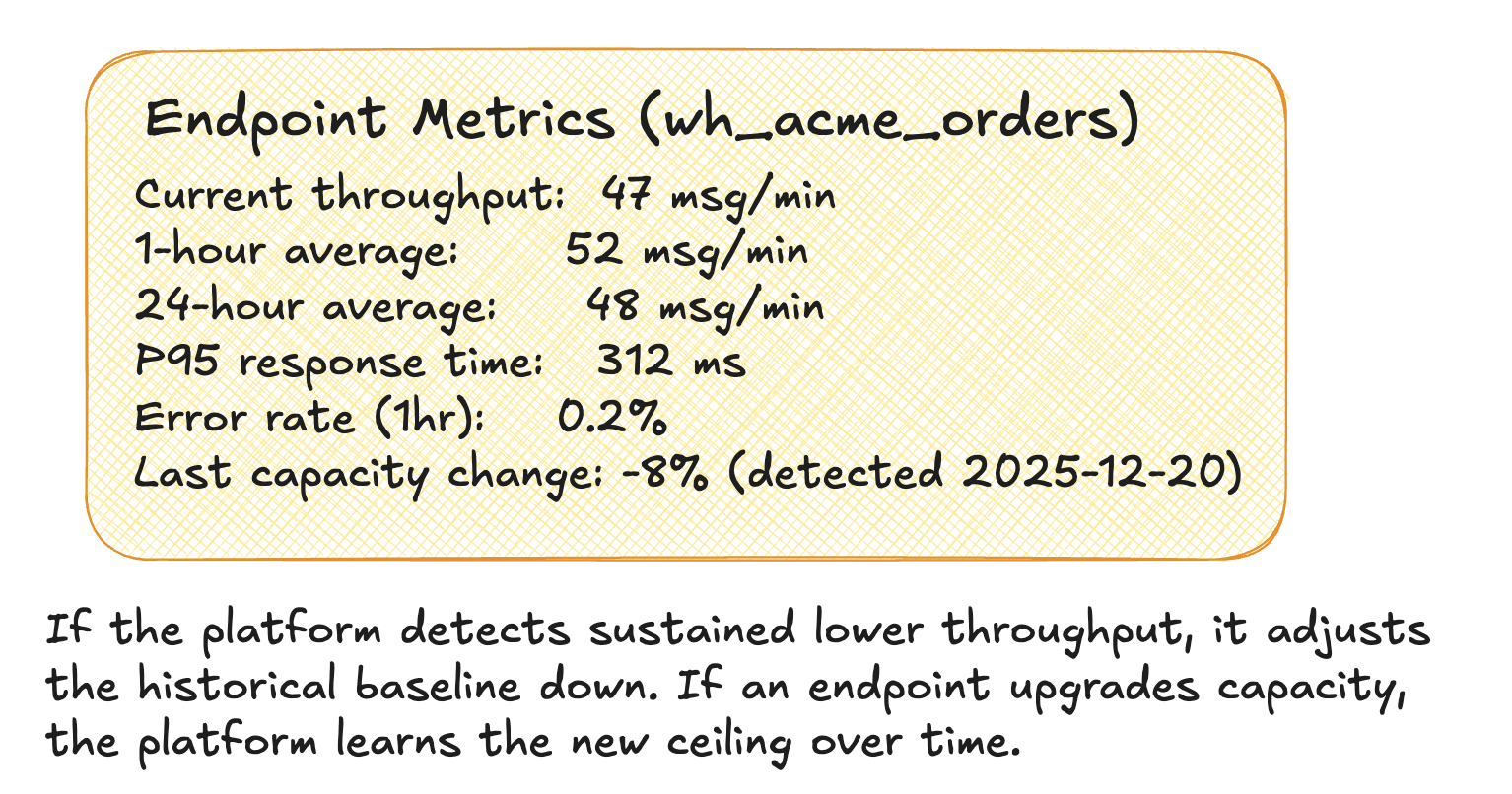

Adaptive Throughput Learning

The platform continuously learns each endpoint’s capacity:

Throughput tracking:

- Record successful deliveries per minute

- Maintain rolling average (e.g., 1-hour window)

- Track P95 response times

- Detect capacity changes over time

This system transforms the dead letter queue from a “failed message graveyard” into an intelligent buffer that coordinates with endpoint health to maximize delivery success while protecting both your platform and your clients’ systems from overload.

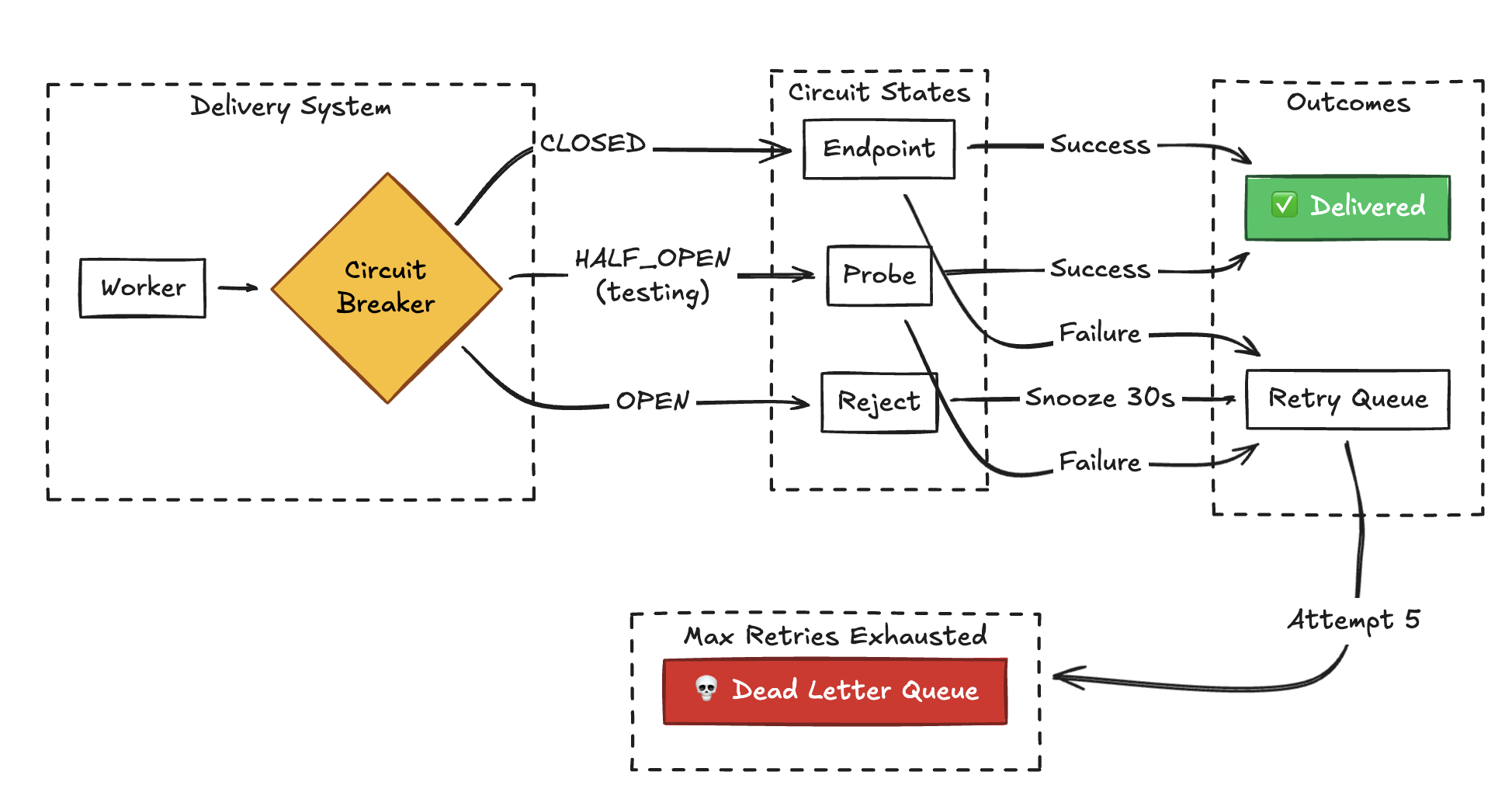

Circuit Breaker: Health Checks Before Replay

The concept of automatically interrupting a system to prevent damage predates software by over a century. In 1879, Thomas Edison described an early form of circuit breaker in a patent application aimed at protecting lighting circuit wiring from short circuits and overloads. While his commercial power distribution ultimately used fuses, the principle was established: detect a dangerous condition, interrupt the flow, prevent cascading failure.

The mathematics are straightforward. When a short circuit occurs, resistance drops dramatically, causing current to spike according to Ohm’s Law:

$$I = \frac{V}{R}$$

As $R \to 0$, current $I \to \infty$. Power dissipation follows:

$$P = I^2 R$$

Even with low resistance, the enormous current creates destructive heat. Edison’s breakthrough was recognizing that you could detect this condition and automatically break the circuit before the wiring caught fire.

From Electricity to Telephony

Telephone networks adopted similar protective patterns. When a trunk group to a particular exchange became congested, the network would stop routing calls there temporarily. This prevented wasting resources on calls that would fail anyway and gave the congested exchange time to recover. The “all circuits busy” recording—technically called the reorder tone—was the circuit breaker in action.

The mathematics of telephone traffic were formalized by A.K. Erlang in 1917 at the Copenhagen Telephone Company. His Erlang B formula calculates the probability that a call will be blocked when all circuits are busy:

$$P_B = \frac{\frac{A^c}{c!}}{\sum_{k=0}^{c} \frac{A^k}{k!}}$$

Where:

- $A$ = traffic intensity in Erlangs (average concurrent calls)

- $c$ = number of circuits (trunks)

- $P_B$ = probability a call is blocked

For example, with 10 trunk lines and 8 Erlangs of traffic (8 simultaneous calls on average), the blocking probability is approximately 1.2%. Add one more Erlang (9 concurrent), and blocking jumps to 4%. The exponential relationship explains why networks implement circuit breakers: a small increase in load can cause disproportionate blocking without protective measures.

The Software Circuit Breaker

Michael Nygard popularized the software circuit breaker pattern in his 2007 book Release It!, directly inspired by these electrical and telephony concepts. Before replaying to a failing endpoint, check if it’s recovered:

Before replay:

- Check circuit state

- If OPEN → reject replay, endpoint still down

- If HALF-OPEN → ping endpoint first

- 200 OK? → CLOSED, proceed with replay

- 429? → schedule retry after Retry-After

- 5xx? → back to OPEN

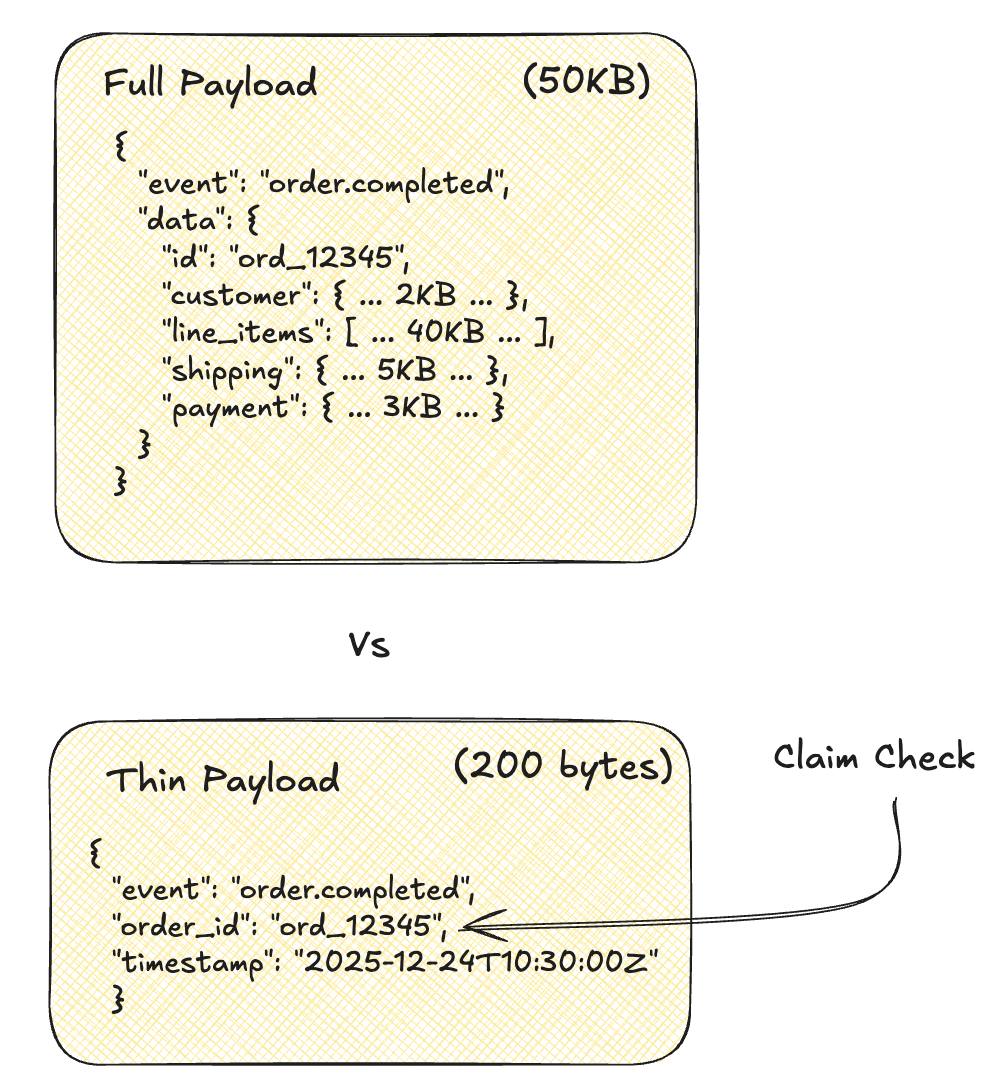

Claim Check: Lightweight Webhooks

Back in Day 5, we introduced the Claim Check pattern as a way to work around message broker size limitations. Remember the coat check analogy? You get a small ticket, not the coat itself. The 5MB invoice PDF goes to S3; the event carries just a reference.

The same pattern solves a different problem for webhooks: bandwidth optimization at scale.

Not every webhook needs the full payload. An order.completed event might have 50KB of line items, shipping details, and customer data. But maybe the client just needs to know which order completed, and they’ll fetch the details if they care.

The Claim Check pattern: send a lightweight notification with a reference, let the client fetch the full payload via your existing API.

Client wants details? Use your existing API:

GET /api/v1/orders/ord_12345 → Full order payload

| Mode | Bandwidth | Latency | Use When |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full | 50KB/event | Single trip | Client needs data immediately |

| Claim Check | 200B/event | Webhook + API call | Client may not need details |

Bandwidth math at scale:

Given $E = 1{,}000{,}000$ events/day, full payload $P_f = 50\text{KB}$, claim check $P_c = 200\text{B}$, and fetch rate $r$:

$$B_{\text{full}} = E \times P_f = 1{,}000{,}000 \times 50\text{KB} = 50\text{GB/day}$$

$$B_{\text{claim}} = E \times P_c + (E \times r) \times P_f = 200\text{MB} + (r \times 50\text{GB})$$

| Fetch Rate ($r$) | Total Bandwidth | Savings |

|---|---|---|

| 100% (no gain) | 50.2 GB | 0% |

| 20% | 10.2 GB | 80% |

| 5% | 2.7 GB | 95% |

The less clients need the full payload, the more you save. Analytics webhooks (“something happened”) often don’t need details. Order notifications (“order shipped”) usually do.

Choosing Your Payload Strategy

Use full (fat) payloads when:

- Clients need to act immediately without additional API calls

- The webhook triggers time-sensitive workflows (payment processing, inventory updates)

- Your API has rate limits that would bottleneck bulk fetches

- Payload sizes are consistently small (<5KB)

- Clients are in regions with high latency to your API

Use claim check (thin) payloads when:

- Many events are informational only (analytics, logging, audit trails)

- Payloads are large or highly variable in size

- Clients already have the data cached locally

- You’re delivering to unreliable endpoints (smaller payloads = faster retries)

- Compliance requires that sensitive data stays in your API (client must authenticate to fetch)

The third option: let the client choose.

The best webhook platforms make payload mode configurable per registration:

POST /api/v1/webhooks

{

"url": "https://client.example.com/hooks",

"events": ["order.completed", "order.refunded"],

"payload_mode": "full" | "thin" | "auto", # Client choice

"include_fields": ["id", "status", "total"] # Or pick fields

}

| Mode | Behavior |

|---|---|

full | Always send complete payload |

thin | Always send claim check only |

auto | Thin for payloads > threshold (e.g., 10KB), full otherwise |

include_fields | Send only specified fields (partial payload) |

The include_fields option is particularly powerful—it’s a middle ground that lets clients request exactly what they need. A client might only care about order.status and order.total, not the full line item array. This is essentially a Content Filter applied at the webhook level.

Stripe, GitHub, and most mature webhook platforms support some variant of this. Don’t force your clients into a one-size-fits-all approach when a simple configuration flag gives them control over their own bandwidth and latency tradeoffs.

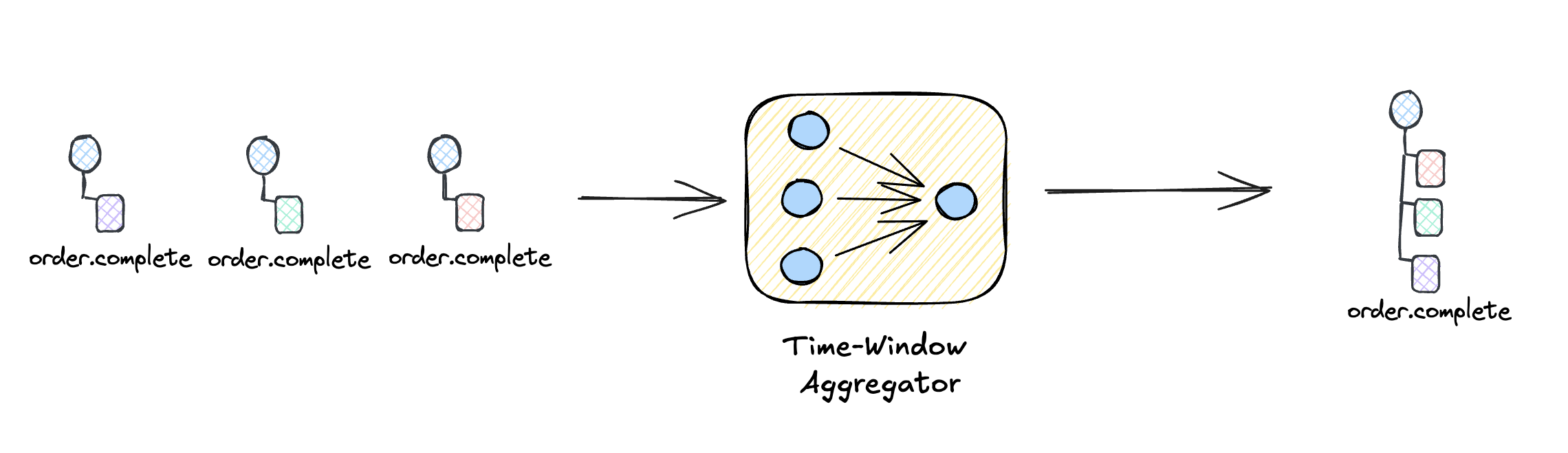

Aggregator: Batching Events

Long-distance telephone calls were expensive because they required dedicated circuits. Time-division multiplexing solved this by batching multiple calls onto a single trunk line, with each call getting a time slice. The overhead of establishing a long-distance circuit was amortized across many conversations.

The same principle applies to webhook delivery. Instead of delivering every event individually, batch events that arrive within a time window.

Each HTTP request has fixed overhead $C$ (connection setup, TLS handshake, headers). If you deliver $E$ events with payload time $p$:

$$T_{\text{individual}} = E \times (C + p)$$

$$T_{\text{batched}} = \lceil E / B \rceil \times (C + B \cdot p)$$

Where $B$ = batch size. With $E = 10{,}000$ events, $C = 100\text{ms}$, $p = 10\text{ms}$, $B = 100$:

| Mode | Connections | Overhead | Payload | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | 10,000 | $10{,}000 \times 100\text{ms} = 1{,}000\text{s}$ | $100\text{s}$ | 1,100s |

| Batched | 100 | $100 \times 100\text{ms} = 10\text{s}$ | $100\text{s}$ | 110s |

Savings: $1 - \frac{110}{1{,}100} = 90%$ reduction in connection overhead

Individual delivery (high overhead):

Event 1 ──► POST /webhook ──► 200 OK

Event 2 ──► POST /webhook ──► 200 OK

Event 3 ──► POST /webhook ──► 200 OK

Event 4 ──► POST /webhook ──► 200 OK

= 4 HTTP connections, 4 round trips

Batched delivery (efficient):

Event 1 ──┐

Event 2 ──┼──► Aggregator ──► POST /webhook ──► 200 OK

Event 3 ──┤ (5s window { events: [1,2,3,4] }

Event 4 ──┘ or 100 max)

= 1 HTTP connection, 1 round trip

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ BATCH CONFIG │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ max_size: 100 Flush when batch hits 100 events │

│ max_wait_ms: 5000 ...or after 5 seconds, whichever first │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Timeline:

t=0ms Event 1 arrives, start 5s timer

t=100ms Event 2 arrives

t=800ms Event 3 arrives

t=2000ms Event 4 arrives

t=5000ms Timer fires → flush batch [1,2,3,4]

OR

t=0ms Events 1-100 arrive rapidly

t=50ms Batch full → flush immediately (don't wait for timer)

Batching adds latency. A 5-second batch window means events can be delayed up to 5 seconds. For real-time use cases, keep batch windows short or use individual delivery.

Implementation Example

In Elixir, a GenServer naturally models this pattern—accumulate events in state, flush on size limit or timer:

defmodule AuditLog.BatchedWebhook do

use GenServer

@max_size 100

@flush_interval :timer.seconds(5)

def start_link(webhook_url), do: GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, webhook_url)

def push(pid, event), do: GenServer.cast(pid, {:push, event})

@impl GenServer

def init(webhook_url) do

schedule_flush()

{:ok, %{url: webhook_url, events: [], count: 0}}

end

@impl GenServer

def handle_cast({:push, event}, %{events: events, count: count} = state) do

state = %{state | events: [event | events], count: count + 1}

if state.count >= @max_size do

{:noreply, flush(state)}

else

{:noreply, state}

end

end

@impl GenServer

def handle_info(:flush, state) do

schedule_flush()

{:noreply, flush(state)}

end

defp flush(%{events: []} = state), do: state

defp flush(%{url: url, events: events} = state) do

# Send batch to customer webhook

Req.post!(url, json: %{events: Enum.reverse(events)})

%{state | events: [], count: 0}

end

defp schedule_flush, do: Process.send_after(self(), :flush, @flush_interval)

end

# Usage: one GenServer per customer webhook

{:ok, acme} = AuditLog.BatchedWebhook.start_link("https://acme.com/webhooks/audit")

# Push events as they happen - they'll batch automatically

AuditLog.BatchedWebhook.push(acme, %{type: "user.login", user_id: 123})

AuditLog.BatchedWebhook.push(acme, %{type: "document.viewed", doc_id: 456})

# ... events accumulate, flush after 5s or 100 events

Each customer gets their own GenServer process—Elixir’s lightweight processes make this practical even with thousands of customers. Events accumulate per-customer, and each webhook receives batches independently.

Signature Verification

Every webhook should be signed so clients can verify authenticity. Without signatures, attackers can forge webhook requests to trigger unintended actions—imagine a fake payment.completed event crediting an account. This is why OWASP recommends HMAC verification as a baseline webhook security control, and why providers like Stripe, GitHub, and Twilio all implement signature verification.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Webhook Request │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ POST /webhooks/orders │

│ X-Webhook-Signature: t=1703412600,v1=5d41402abc4b2a76... │

│ Content-Type: application/json │

│ │

│ { "event": "order.completed", "order_id": "ord_12345" } │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Signature construction:

1. timestamp = 1703412600 (Unix seconds)

2. payload = '{"event":"order.completed",...}'

3. signature_input = "1703412600.{payload}"

4. signature = HMAC-SHA256(signature_input, webhook_secret)

5. header = "t={timestamp},v1={base64(signature)}"

Client verification:

1. Parse t= and v1= from header

2. Check |now - t| < 300 seconds (prevent replay)

3. Recompute HMAC with their copy of secret

4. Compare signatures (constant-time!)

5. ✓ Match = authentic, ✗ Mismatch = reject

Bulkhead: Isolating Tenant Traffic

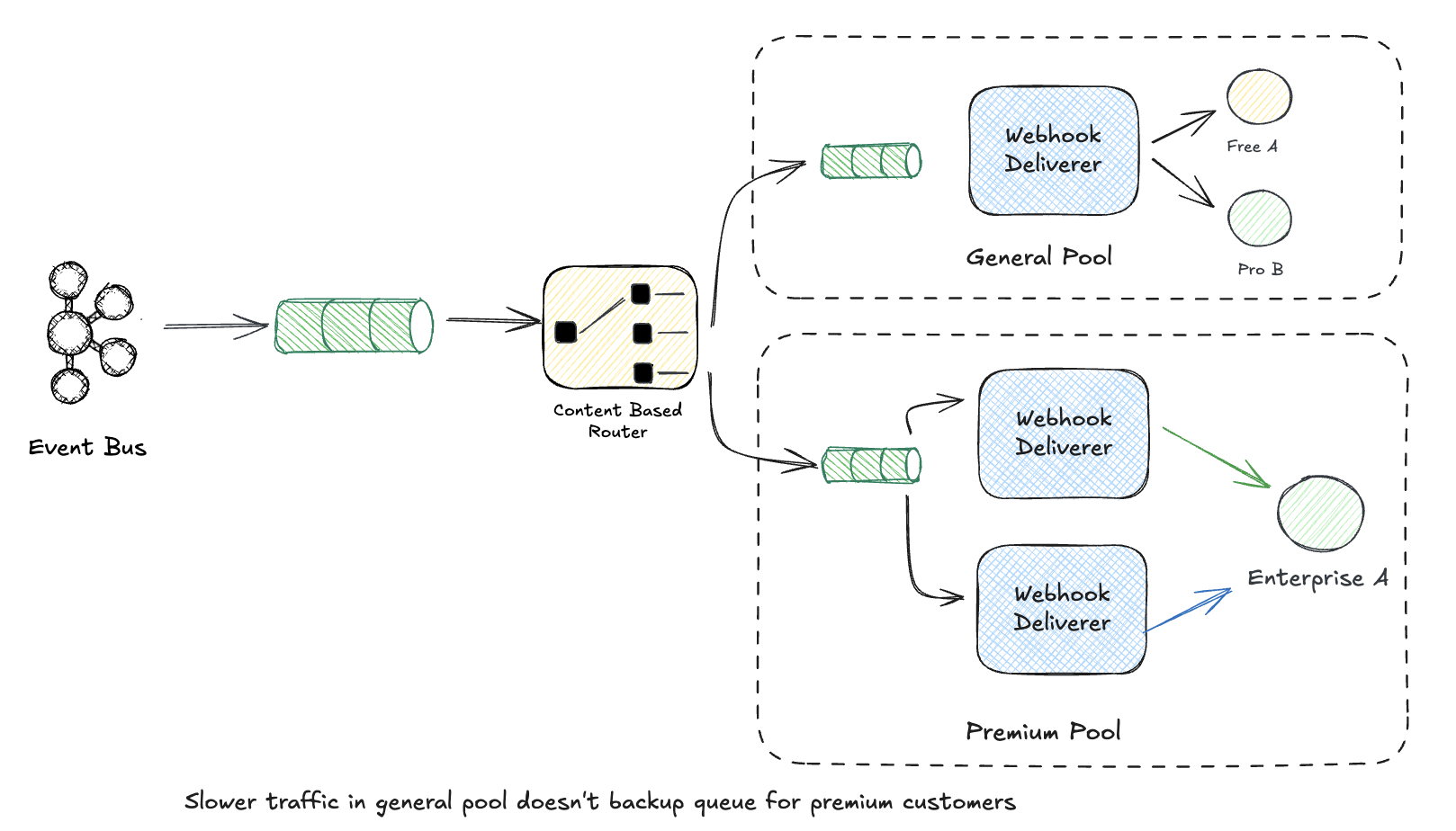

Telephone networks organized trunk lines into trunk groups, and the Bell System engineers learned early that some customers needed isolation. They invented the concept of “choke exchanges"—special exchanges assigned to high-volume users like radio and TV stations running call-in contests. These exchanges had limited trunk capacity by design. When thousands of listeners tried to be “caller number 9,” the choke exchange would saturate, but normal users on other exchanges could still make calls. The noisy neighbor was contained.

Trunk groups were also engineered with different grades of service. Common trunks might be designed for B.01 blocking (1% of calls blocked during peak), while dedicated final trunk groups for important routes got B.005 (0.5% blocking)—twice the reliability through resource isolation.

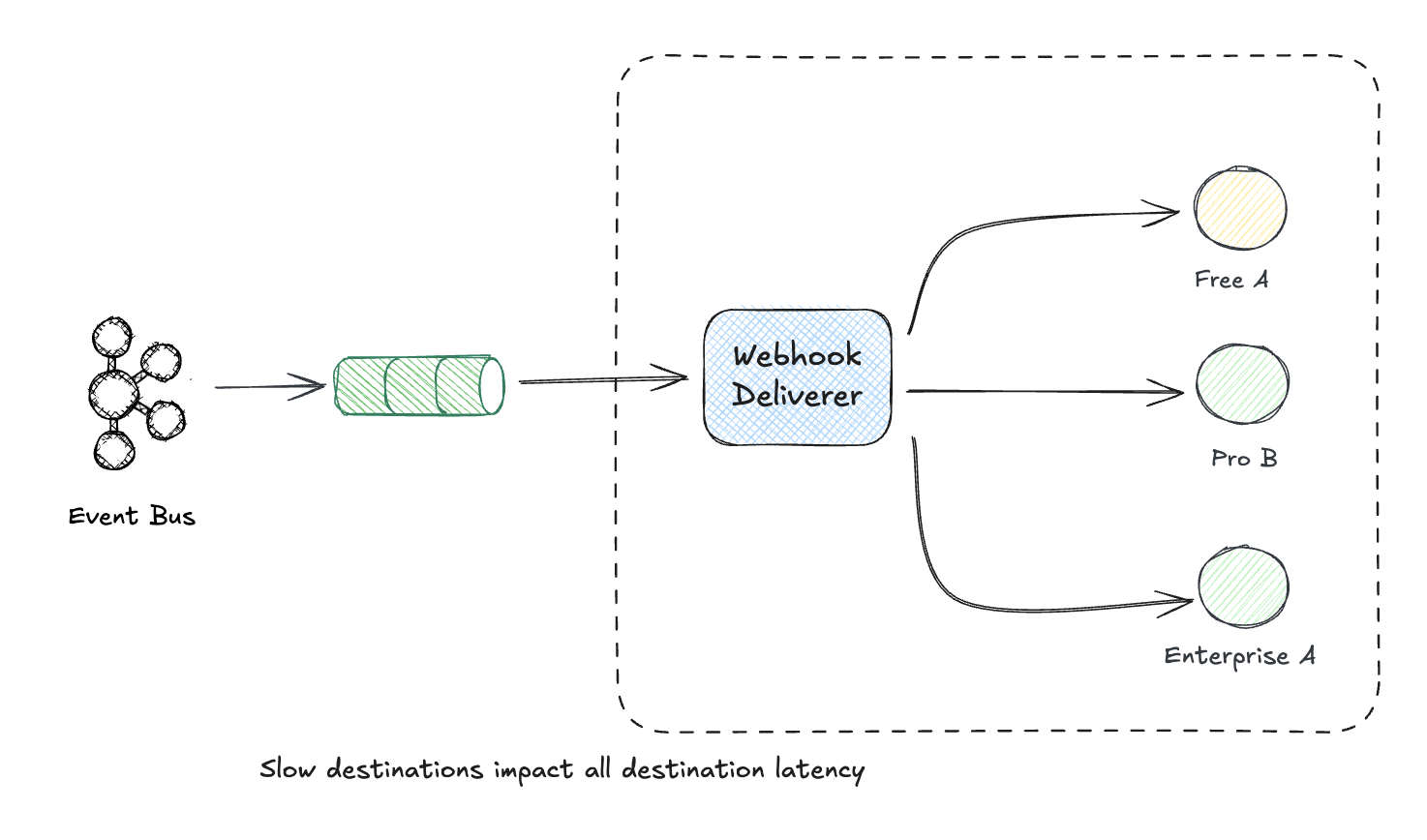

The same isolation principle applies to webhook delivery. Without bulkheads, one customer’s misbehaving endpoint can degrade delivery for everyone:

Without a bulkhead:

With a Bulkhead:

Each tier gets its own bulkhead with different guarantees:

| Tier | Queue | Workers | Rate Limit | Retries | DLQ TTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterprise | Dedicated | 10 | 100/s | 5 (1s backoff) | 30 days |

| Standard | Shared | 5 | 20/s | 3 (5s backoff) | 7 days |

| Free | Shared | 2 | 5/s | 1 (30s backoff) | 1 day |

Enterprise customers paying $100k/year get dedicated infrastructure. A free user’s failing webhook endpoint never affects them. This is the noisy neighbor problem solved through isolation.

The pattern extends beyond webhook delivery. You can apply bulkheads at every layer:

- Ingestion: Separate API pools per tier

- Processing: Dedicated worker pools

- Storage: Isolated clusters for high-volume tenants

- Delivery: Tier-specific queues and retry policies

The Pattern Inventory

Look at what we’ve assembled:

| Pattern | Role in Webhook Platform |

|---|---|

| Recipient List | Route events to multiple webhook destinations |

| Content Filter | Filter events by type or JSONPath expression |

| Retry | Exponential backoff on delivery failure |

| Dead Letter Queue | Capture failed deliveries for inspection/replay |

| Command Message | Trigger replays, purges, health checks |

| Circuit Breaker | Stop hammering unhealthy endpoints |

| Bulkhead | Isolate tenant traffic, prevent noisy neighbor |

| Claim Check | Lightweight webhooks, client fetches full payload |

| Aggregator | Batch events within time windows |

| Message Expiration | TTL on stored events |

| Correlation ID | Track events through the entire pipeline |

This is how patterns compose into real systems. Each one solves a specific problem; together they form a robust, scalable platform.

What’s Next

We’ve built a production-grade webhook delivery platform. But notice something: the pipeline is stateful and multi-step. An event flows through recipient matching, delivery attempts, retries, and potentially dead letter handling. Each step changes state. Each step can fail.

What happens when a batch delivery partially succeeds? Three webhooks get the event, but two fail. You retry the failures, but now the client has duplicate events. Or worse: you’re processing an order, charge the card successfully, then the inventory check fails. The money is gone but there’s no product to ship.

These are coordination problems. And they need a coordinator.

Tomorrow we’ll tackle Process Manager / Saga patterns: orchestrating multi-step workflows with compensation logic for when things go wrong.

See you on Day 9! 🎄

This post is part of the Advent of Enterprise Integration Patterns series. Check out the introduction or follow along with the enterprise-integration-patterns tag. All patterns referenced are from the classic book Enterprise Integration Patterns by Gregor Hohpe and Bobby Woolf.

A note on AI usage: I used Claude as a writing assistant for this series, particularly for generating code samples that illustrate the patterns. The patterns, architectural insights, and real-world experiences are mine. I believe in transparency about these tools.