Message Translation, Content Enricher, Content Filter, Canonical Data Model - these patterns don’t get as much attention as the flashier routing patterns, but they’re where the real work happens. Every integration I’ve built has needed at least one of them.

When systems talk to each other, they rarely agree on data formats. Your e-commerce platform calls it a “customer,” your CRM calls it a “contact,” and your billing system calls it an “account holder.” They all mean the same thing, but their schemas don’t match. Multiply this across dozens of integrations and you’ve got a translation nightmare.

Today’s patterns provide the solution: a Canonical Data Model that serves as a shared vocabulary, plus transformation patterns that convert messages to and from that common language.

The N×N Translation Problem

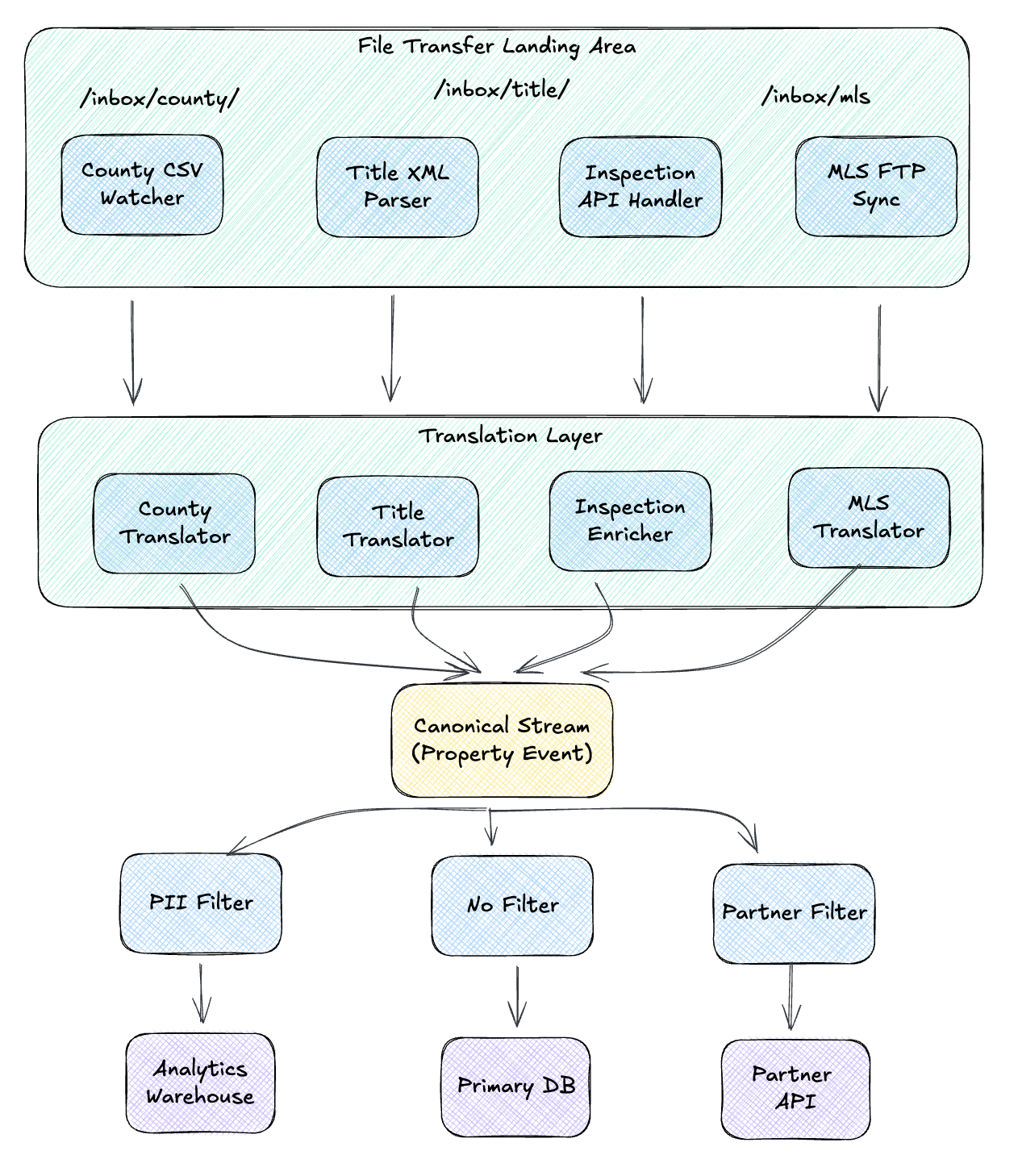

I’m going to use a property data aggregation platform as our running example. Think of systems that consolidate real estate information from multiple sources to provide a unified view. I’ve built systems like this, and the pattern applies broadly to any domain where you’re aggregating data from diverse external sources.

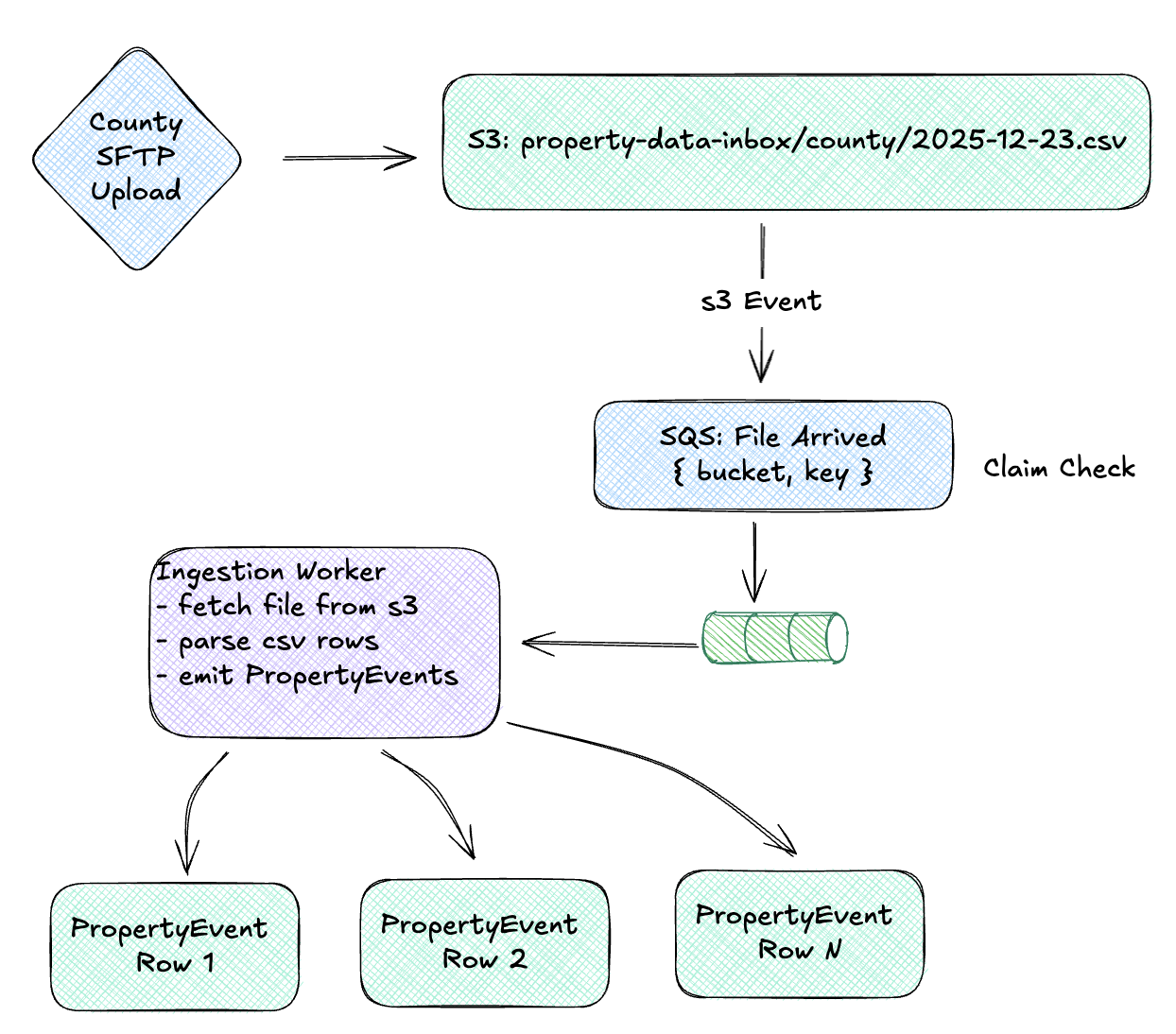

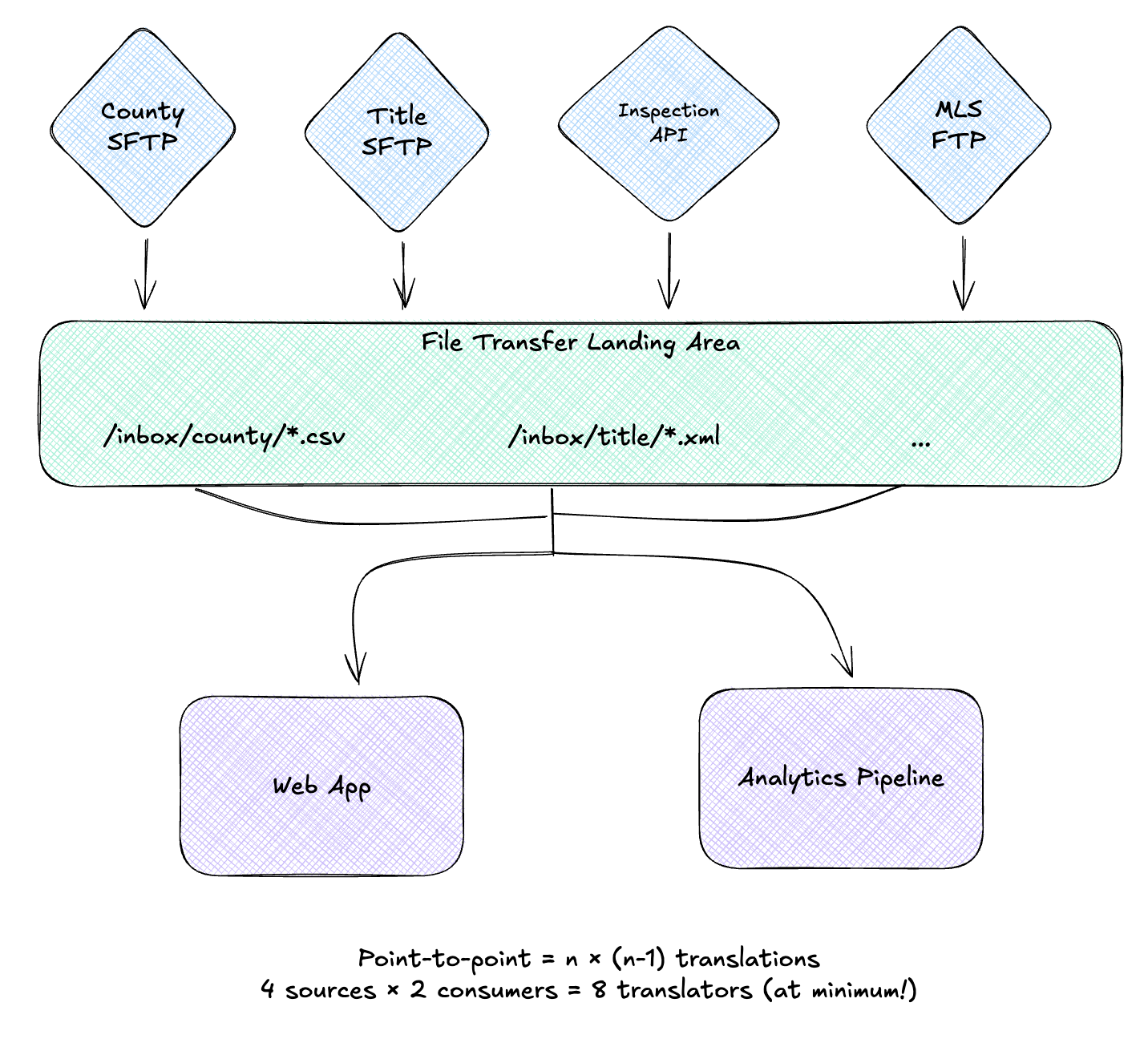

Data flows in from county records offices, title companies, inspection services, and MLS feeds. Most of these sources land via File Transfer, the pattern we covered on Day 1. County assessors aren’t calling your REST API; they’re dropping CSV files on an SFTP server overnight. Title companies send batched XML. The file transfer pattern gets data into your system, but then you need to transform it into something useful.

A modern implementation might look like this: SFTP gateway (AWS Transfer Family or similar) in front of S3 buckets. Partners upload to what looks like a traditional SFTP server, but files land in s3://property-data-inbox/county/, s3://property-data-inbox/title/, etc. S3 event notifications fire when files arrive, publishing a message containing the bucket and key, a Claim Check. The actual 50MB CSV doesn’t travel through your message broker; just a reference to where it lives. A worker picks up that claim check, pulls the file from S3, iterates through the rows, and emits individual PropertyEvent messages to the canonical stream.

So let’s imagine the inbound data:

- County assessors drop property records as CSVs on SFTP

- Title companies send ownership transfers as batched XML files

- Inspection services submit reports through a REST API

- MLS feeds deliver listing updates in fixed-width format

Each source has its own schema, its own field names, its own conventions. A property identifier might be parcel_id, APN, property_id, or tax_lot_number. Addresses could be 123 Main St, 123 MAIN STREET, or split across five fields (address normalization is its own rabbit hole). Dates could be 2025-12-23, 12/23/2025, 23-Dec-2025, or a Unix timestamp.

The Canonical Data Model

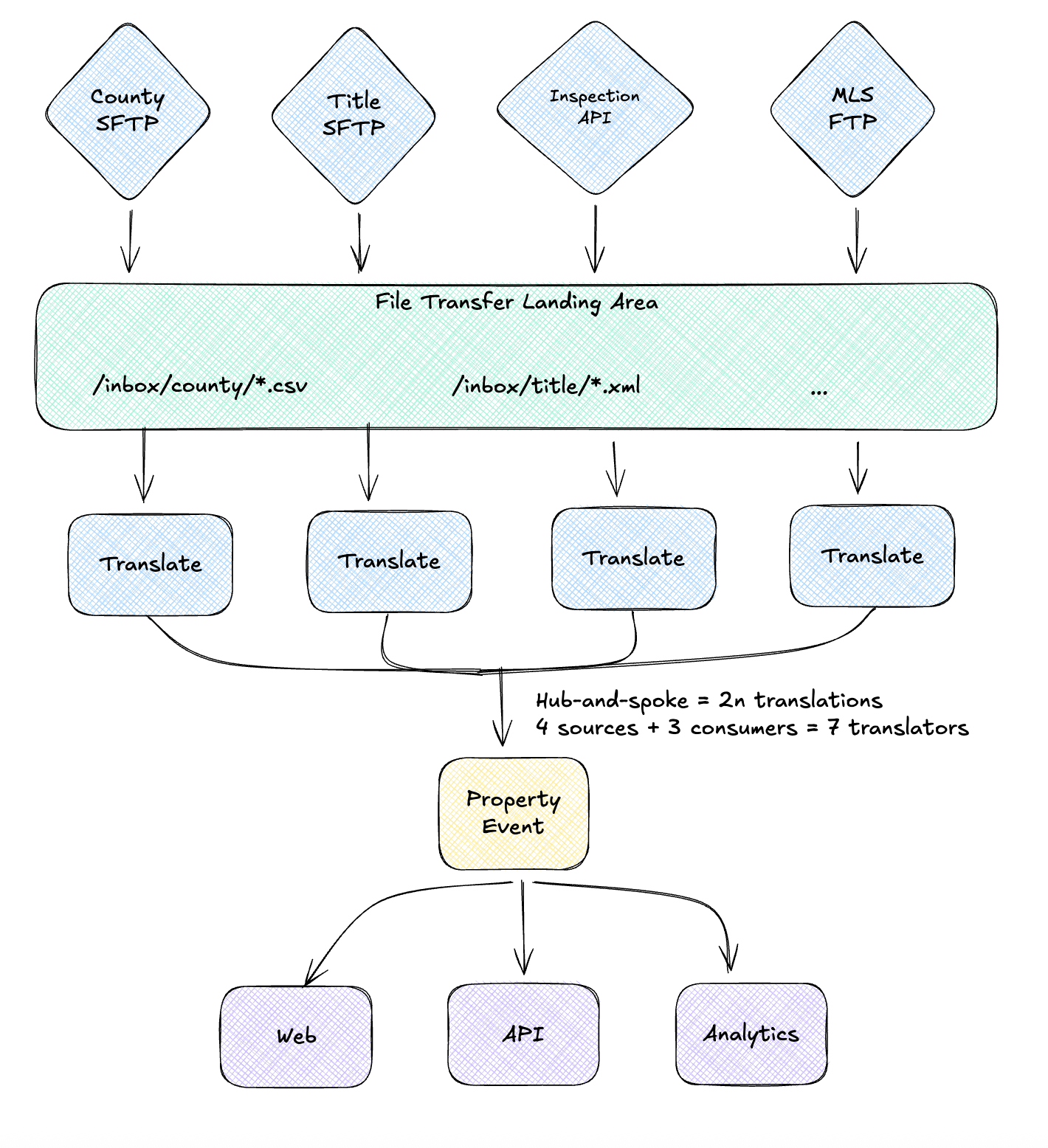

The Canonical Data Model pattern cuts through this complexity:

“Design a Canonical Data Model that is independent from any specific application. Require each application to produce and consume messages in this common format.”

Instead of point-to-point translations, every system speaks one common language. Now you need only 2n transformations: one “to canonical” and one “from canonical” for each system.

Key characteristics:

- Application-independent: The canonical model doesn’t belong to any single system

- Domain-focused: Models the business concepts, not technical concerns

- Stable: Changes slowly compared to individual system schemas

- Complete enough: Covers the union of fields that any consumer might need

Modern Standards for Canonical Models

This topic deserves its own post, but here’s the quick version. Three specs worth knowing, and being upfront about contracts early pays off:

AsyncAPI is the easiest place to start. It’s OpenAPI for event-driven systems: you define your channels, message schemas (using JSON Schema inline), and broker bindings. You get documentation, validation, and code generation. For most teams, this is enough.

CloudEvents standardizes the envelope around your events: source, type, id, time, datacontenttype. Your business payload goes in data. It’s lightweight and gives you interoperability across different tools and transports. Worth adopting if you’re integrating with external systems or multiple cloud services.

Apache Avro (or Protocol Buffers) adds schema evolution guarantees and binary serialization. You need this if JSON is too slow, payloads are huge, or you want strict forward/backward compatibility rules enforced by a Schema Registry. Most teams don’t need it on day one.

My recommendation: Start with AsyncAPI and JSON Schema. Add CloudEvents if you need cross-system interop. Reach for Avro when you hit performance limits or need strict evolution guarantees. You can always layer them - AsyncAPI can reference Avro schemas in the payload definition.

The Property Data Canonical Model

For our aggregation system, the canonical model captures what matters across all event types:

import birl.{type Time}

import gleam/option.{type Option}

import youid/uuid.{type Uuid}

/// The canonical property event that all sources translate into

pub type PropertyEvent {

PropertyEvent(

event_id: Uuid,

property_id: String,

address: NormalizedAddress,

occurred_at: Time,

event_type: EventType,

source: EventSource,

details: EventDetails,

)

}

pub type EventType {

Assessment

Transfer

Listing

Inspection

Permit

}

pub type EventSource {

EventSource(system: String, original_id: String)

}

pub type EventDetails {

TransferDetails(Transfer)

AssessmentDetails(Assessment)

ListingDetails(Listing)

InspectionDetails(InspectionReport)

}

pub type Transfer {

Transfer(

grantor: Option(PartyInfo),

grantee: PartyInfo,

sale_price: Option(Money),

recorded_at: Time,

document_number: String,

)

}

Every incoming message gets translated into this shape. Downstream consumers don’t care if data came from CSV, XML, or a REST API - they just read PropertyEvent.

When Canonical Models Emerge Organically

Canonical data models rarely spring from elegant upfront design. They emerge from necessity.

I was working on a platform where four separate product verticals had been evolving independently for years. Each had its own codebase, database, and event system. Then came the mandate: integrate everything into a single management plane. Users needed to interact with resources from all four products seamlessly: organizing them into collections, trashing items, restoring from trash.

The challenge? Each system had a different relationship with events:

- Two systems emitted CRUD events but with wildly different schemas

- One had a partial soft-delete implementation with its own event vocabulary

- The fourth had “emit events” somewhere on next quarter’s roadmap

The solution was a canonical ResourceLifecycle event schema, a shared vocabulary that all four domains could speak. Some systems adopted it natively; others got a message translation layer to convert their existing events.

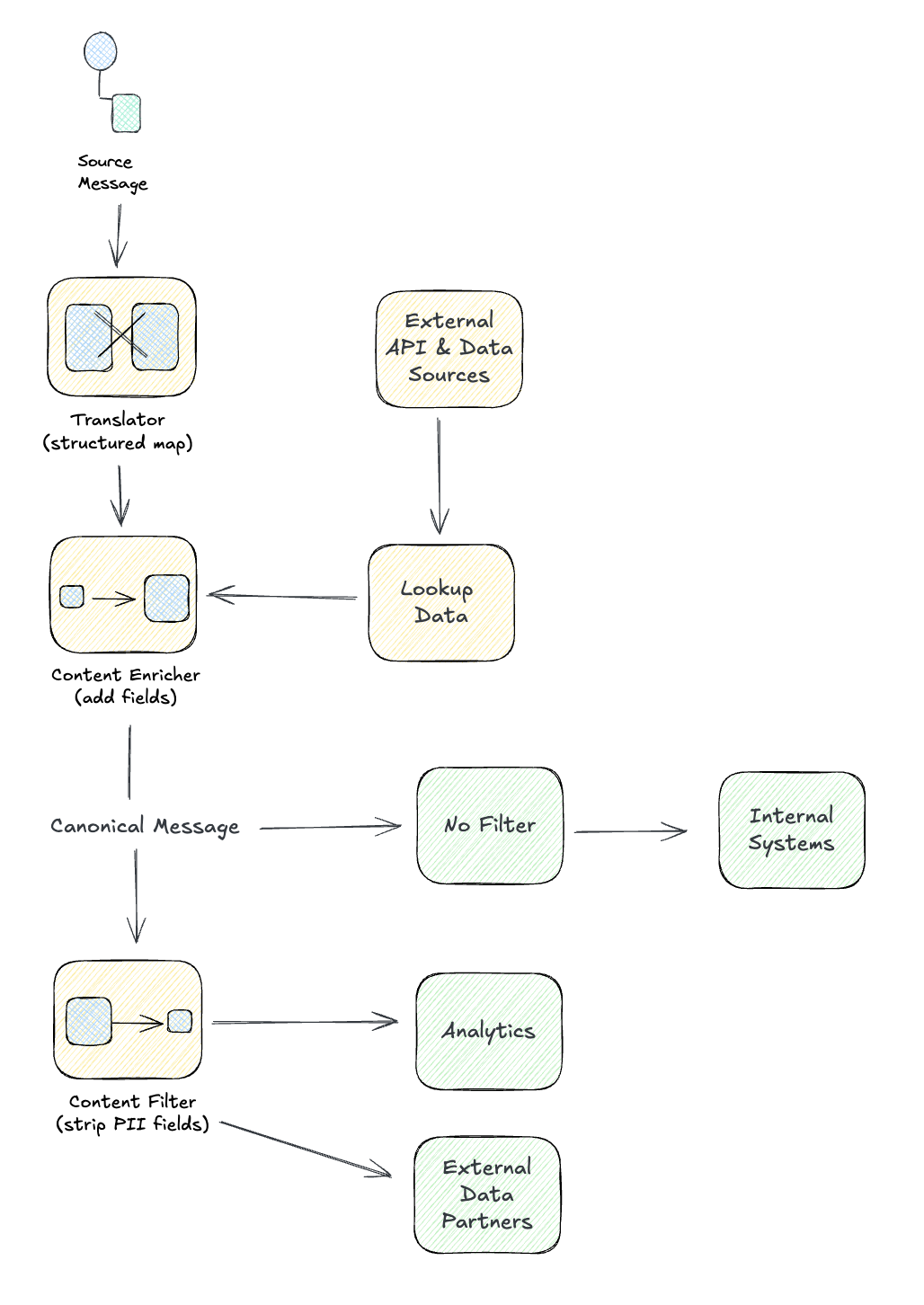

What made this interesting is how the three transformation patterns naturally emerged:

- Content Enricher: Some events lacked required fields like

workspace_id, so the translation layer called APIs to look up the missing data before producing the canonical event. - Content Filter: Legacy events carried internal fields (audit metadata, system flags) that downstream consumers didn’t need. These were stripped at the boundary.

- Message Translator: One system’s

chatbot_enabledevent mapped to our canonicalresource_enabled, pure structural transformation.

The canonical model didn’t just enable a unified user experience. It unlocked future capabilities. New features could subscribe to ResourceLifecycle events without caring which product originated them.

Three Transformation Patterns

The Canonical Data Model is an architectural principle. To implement it, you need three transformation patterns:

| Pattern | Purpose | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Message Translator | Convert between formats | Source → Canonical structure mapping |

| Content Enricher | Add missing data | Lookup external data to complete message |

| Content Filter | Remove unnecessary data | Strip fields for specific consumers |

Message Translator

The Message Translator is the workhorse of data transformation:

“Use a special filter, a Message Translator, between other filters or applications to translate one data format into another.”

A translator’s job is pure: take a message in format A, output a message in format B. No side effects, no external calls, just structure mapping.

County Records CSV to Canonical

The county sends property assessments as CSV with their own conventions. We translate using pure functions and the pipe operator:

import birl

import gleam/dict.{type Dict}

import gleam/int

import gleam/result

import gleam/string

import youid/uuid

/// Translate a county CSV row into our canonical PropertyEvent

pub fn translate_county_record(

row: Dict(String, String),

) -> Result(PropertyEvent, TranslationError) {

use parcel <- result.try(

row

|> dict.get("PARCEL_NUM")

|> result.map(normalize_parcel)

|> result.replace_error(MissingField("PARCEL_NUM"))

)

use date <- result.try(

row

|> dict.get("ASSESS_DATE")

|> result.then(parse_mdy_date)

|> result.replace_error(InvalidDate)

)

use assessed_val <- result.try(

row

|> dict.get("ASSESSED_VAL")

|> result.then(int.parse)

|> result.replace_error(InvalidNumber("ASSESSED_VAL"))

)

let address =

row

|> dict.get("SITE_ADDR")

|> result.map(normalize_address)

|> result.unwrap(empty_address())

Ok(PropertyEvent(

event_id: uuid.v4(),

property_id: parcel,

address: address,

occurred_at: date,

event_type: Assessment,

source: EventSource(system: "county", original_id: parcel),

details: AssessmentDetails(Assessment(

owner_name: dict.get(row, "OWNER_NAME") |> result.unwrap(""),

assessed_value: assessed_val,

land_value: dict.get(row, "LAND_VAL")

|> result.then(int.parse)

|> result.unwrap(0),

)),

))

}

fn normalize_parcel(raw: String) -> String {

raw

|> string.trim

|> string.uppercase

|> string.replace("-", "")

}

The translator handles all the county quirks: MM/DD/YYYY dates, PARCEL_NUM field names, address normalization. Downstream consumers only see the canonical shape.

Title Company XML to Canonical

Title companies send ownership transfers as XML. Same pattern, different parser:

import gleam/result

import xmb.{type Node} // hypothetical XML library

/// Translate title company XML into canonical PropertyEvent

pub fn translate_title_transfer(doc: Node) -> Result(PropertyEvent, TranslationError) {

use apn <- result.try(

doc

|> xmb.find_text("Property/APN")

|> result.map(normalize_parcel)

|> result.replace_error(MissingField("Property/APN"))

)

use recorded_date <- result.try(

doc

|> xmb.find_text("RecordedDate")

|> result.then(birl.parse)

|> result.replace_error(InvalidDate)

)

use doc_number <- result.try(

doc

|> xmb.find_text("DocumentNumber")

|> result.replace_error(MissingField("DocumentNumber"))

)

let sale_price =

doc

|> xmb.find_text("SalePrice")

|> result.then(parse_money)

|> option.from_result

Ok(PropertyEvent(

event_id: uuid.v4(),

property_id: apn,

address: doc |> xmb.find("Property/Address") |> parse_address,

occurred_at: recorded_date,

event_type: Transfer,

source: EventSource(system: "title", original_id: doc_number),

details: TransferDetails(Transfer(

grantor: doc |> xmb.find_text("Grantor/Name") |> option.from_result,

grantee: doc |> xmb.find_text("Grantee/Name") |> result.unwrap("Unknown"),

sale_price: sale_price,

recorded_at: recorded_date,

document_number: doc_number,

)),

))

}

Two completely different source formats, one canonical output.

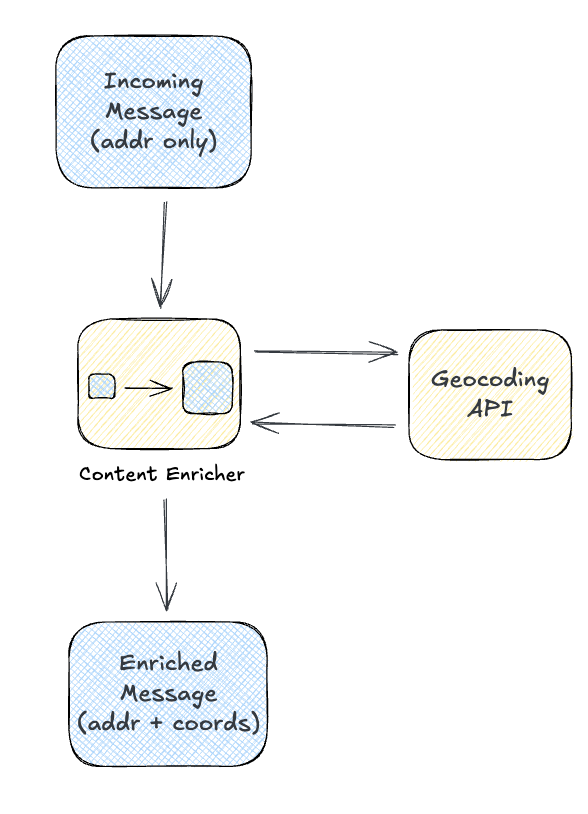

Content Enricher

The Content Enricher pattern augments a message with data from external sources:

“Use a specialized transformer, a Content Enricher, to access an external data source in order to augment a message with missing information.”

Sometimes the incoming message doesn’t have everything downstream consumers need. An address isn’t coordinates, but you can geocode it. A parcel number from one county might need cross-referencing to your canonical ID. The enricher fills in these gaps.

Address to Coordinates Lookup

Inspection services might submit reports with just an address. We enrich with geocoded coordinates and our canonical property ID:

import gleam/otp/task

import gleam/result

pub type Enricher {

Enricher(

geocoder: fn(String) -> Result(Coordinates, GeoError),

property_lookup: fn(String) -> Result(String, LookupError),

)

}

/// Enrich an inspection report with geocoded coordinates and property ID

pub fn enrich_inspection(

enricher: Enricher,

report: InspectionReport,

) -> Result(PropertyEvent, EnrichmentError) {

// Run lookups concurrently using tasks

let coords_task = task.async(fn() { enricher.geocoder(report.address) })

let property_task = task.async(fn() { enricher.property_lookup(report.address) })

// Await both results

use coords <- result.try(

task.await_forever(coords_task)

|> result.map_error(GeocodingFailed)

)

use property_id <- result.try(

task.await_forever(property_task)

|> result.map_error(PropertyNotFound)

)

Ok(PropertyEvent(

event_id: uuid.v4(),

property_id: property_id,

address: report.address |> normalize_address,

coordinates: option.Some(coords),

occurred_at: report.inspection_date,

event_type: Inspection,

source: EventSource(system: "inspector", original_id: report.report_id),

details: InspectionDetails(report.findings),

))

}

Notice we’re calling two external services: the geocoder and our property lookup. The enricher is where that complexity lives, keeping the downstream consumers simple. (This is also where you’d add OpenTelemetry spans to trace the enrichment calls.)

Enrichment Strategies

| Strategy | When | Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|

| Synchronous | During message processing | Adds latency, always fresh |

| Async pre-fetch | Before message hits queue | Better throughput, may be stale |

| On-demand | When consumer needs it | Minimal storage, complex consumers |

For geocoding, synchronous makes sense: we need coordinates before storing, and addresses don’t move.

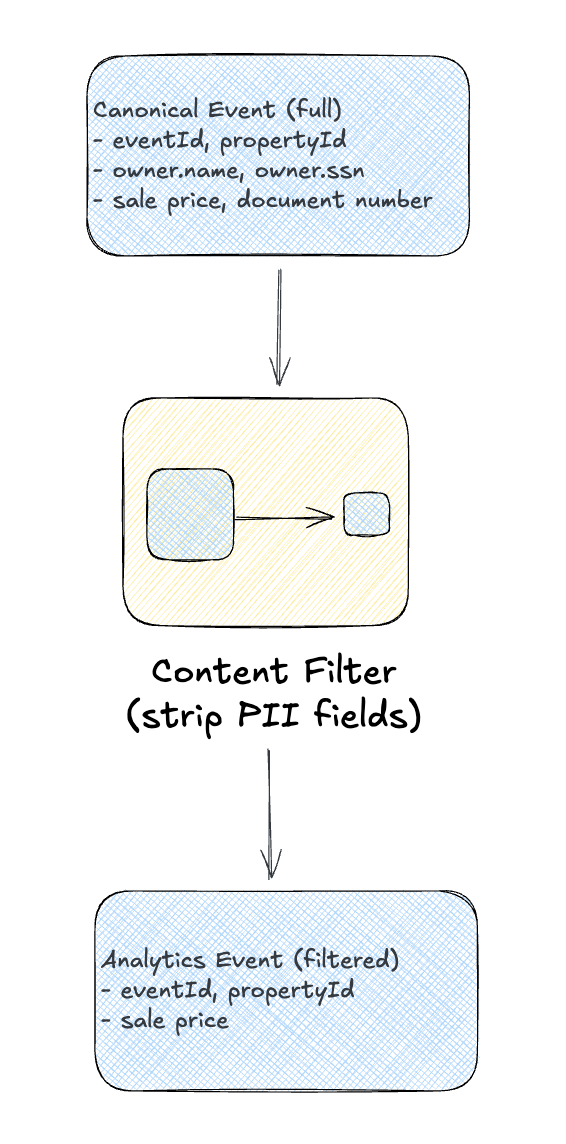

Content Filter

The Content Filter is the opposite of enrichment. It removes data:

“Use a Content Filter to remove unimportant data items from a message, leaving only the important items.”

Why filter content?

- Privacy: Remove PII before sending to analytics

- Efficiency: Drop large fields that consumers don’t need

- Security: Prevent sensitive data from crossing domain boundaries

- Compliance: Ensure certain fields never leave a region

PII Removal for Analytics

The analytics team wants property events but shouldn’t see owner names or SSNs:

/// Filtered event for analytics consumption (no PII)

pub type AnalyticsEvent {

AnalyticsEvent(

event_id: Uuid,

property_id: String,

occurred_at: Time,

event_type: EventType,

source_system: String,

sale_price: Option(Money),

assessed_value: Option(Int),

// No owner info, no addresses, no SSNs

)

}

/// Filter a PropertyEvent down to analytics-safe fields

pub fn filter_for_analytics(event: PropertyEvent) -> AnalyticsEvent {

let #(sale_price, assessed_value) = case event.details {

TransferDetails(t) -> #(t.sale_price, option.None)

AssessmentDetails(a) -> #(option.None, option.Some(a.assessed_value))

_ -> #(option.None, option.None)

}

AnalyticsEvent(

event_id: event.event_id,

property_id: event.property_id,

occurred_at: event.occurred_at,

event_type: event.event_type,

source_system: event.source.system,

sale_price: sale_price,

assessed_value: assessed_value,

)

}

/// Filter multiple events, dropping any that fail

pub fn filter_batch(events: List(PropertyEvent)) -> List(AnalyticsEvent) {

events

|> list.map(filter_for_analytics)

}

The filter is explicit about what it keeps. This is safer than enumerating what to remove; new PII fields won’t accidentally leak through.

Putting It Together: The Property Event Pipeline

Here’s the complete flow:

The code below illustrates the concepts in a single module for clarity. In a real system, these translators, enrichers, and filters would be separate components connected by message channels and queues. The county translator might consume from a county-raw queue and publish to a property-events topic. The analytics filter might subscribe to that topic and write to a property-events-analytics queue. The patterns stay the same; the wiring becomes infrastructure.

import gleam/dict.{type Dict}

import gleam/list

import gleam/otp/task

import gleam/result

pub type Pipeline {

Pipeline(

enricher: Enricher,

analytics_sink: fn(AnalyticsEvent) -> Result(Nil, SinkError),

primary_sink: fn(PropertyEvent) -> Result(Nil, SinkError),

partner_sink: fn(PartnerEvent) -> Result(Nil, SinkError),

)

}

/// Process a raw inbound message through the pipeline

pub fn process(

pipeline: Pipeline,

source: String,

raw: RawMessage,

) -> Result(Nil, PipelineError) {

// Step 1: Translate or enrich to canonical

use canonical <- result.try(

raw

|> translate_to_canonical(source, pipeline.enricher)

|> result.map_error(TranslationFailed)

)

// Step 2: Fan out to consumers with appropriate filtering

let analytics = canonical |> filter_for_analytics

let partner = canonical |> filter_for_partner

// Step 3: Publish to all sinks concurrently

let primary_task = task.async(fn() { pipeline.primary_sink(canonical) })

let analytics_task = task.async(fn() { pipeline.analytics_sink(analytics) })

let partner_task = task.async(fn() { pipeline.partner_sink(partner) })

// Await all

[primary_task, analytics_task, partner_task]

|> list.map(task.await_forever)

|> result.all

|> result.map(fn(_) { Nil })

|> result.map_error(SinkFailed)

}

fn translate_to_canonical(

raw: RawMessage,

source: String,

enricher: Enricher,

) -> Result(PropertyEvent, TranslationError) {

case source {

"county" -> raw.csv_row |> translate_county_record

"title" -> raw.xml_doc |> translate_title_transfer

"inspection" -> raw.inspection |> enrich_inspection(enricher, _)

"mls" -> raw.listing |> translate_mls_listing

_ -> Error(UnknownSource(source))

}

}

Adding a new source? Write one translator. Adding a new consumer? Write one filter. The canonical model in the middle keeps things from exploding.

Signs You Need a Canonical Model

You rarely design a canonical model upfront. They emerge from pain:

Point-to-Point: You integrate county records with your database. One translation, no big deal.

Growing Complexity: You add title data. Now you have County → DB, Title → DB, County → Analytics. Each slightly different.

Breaking Point: You add MLS feeds. And inspection data. And a partner API. Each new system multiplies the translation burden. Someone spends a sprint fixing a bug that existed in three different translators.

Canonical Model: Someone says, “What if we defined a standard format?” You build it, migrate the translators, and suddenly adding new systems is easy again.

Warning signs:

- Multiple teams writing similar translation code

- The same bug appearing in different integrations

- Adding a new source requires touching many systems

- Different consumers have inconsistent views of the same entity

For more on this evolution, see Martin Fowler’s Consumer-Driven Contracts and Bounded Context (which explains why translation happens at context boundaries), plus the original Canonical Data Model pattern from EIP.

What’s Next

We’ve covered how to reshape data as it flows through your system. But so far, our messages have been one-way: fire and forget. What happens when you need a response?

Tomorrow we’ll explore Request-Reply & Correlation patterns:

- Correlation Identifier: Matching responses to their originating requests

- Return Address: Telling services where to send replies

- Request-Reply: Synchronous vs asynchronous approaches

- Message Expiration: Handling timeouts gracefully

These patterns are the foundation for multi-step workflows and distributed conversations.

See you on Day 7! 🎄

This post is part of the Advent of Enterprise Integration Patterns series. Check out the introduction or follow along with the enterprise-integration-patterns tag. All patterns referenced are from the classic book Enterprise Integration Patterns by Gregor Hohpe and Bobby Woolf.

A note on process: I used Claude to help structure the code examples and organize the patterns into logical groupings. The concepts and opinions are mine, informed by the sources cited and practical experience.