Today we’re answering the question, “Should I name my event OrderPlaced or PlaceOrder?” We’re going to be getting more precise about something we’ve been pretty casual about: what exactly is a message?

We’ve been tossing events around without much ceremony. But not all messages are alike. Some carry data. Some request actions. Some announce facts. Understanding these distinctions (and how much data events should carry) shapes how your systems communicate.

Three Questions About Messages

Today’s patterns answer three fundamental questions about messages:

What is this message for?

- Section: Message Types by Intent

- Patterns: Document, Command, Event Messages

How much data should it carry?

- Section: The Payload Spectrum

- Patterns: Event Notification, Event-Carried State, Claim Check

How do we represent change?

- Section: Representing State Changes

- Patterns: Delta Events, Full-State Events, Enriched Events

Let’s work through each one.

Message Types by Intent

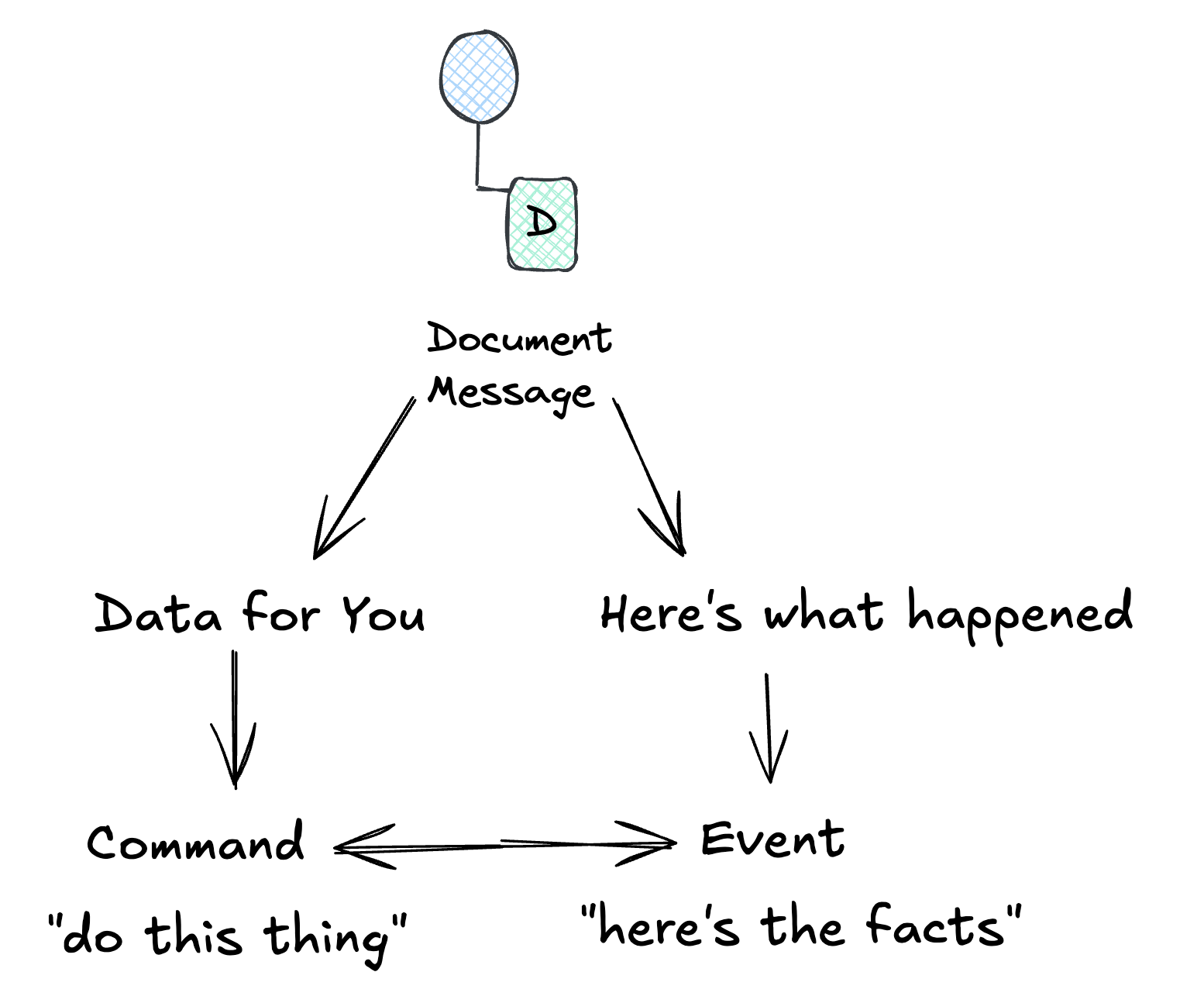

The Enterprise Integration Patterns book identifies three fundamental message types, distinguished by what they’re for:

| Type | Intent | Sender Expectation | Receiver Obligation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Document Message | “Here is data” | Receiver will use it | Process the data |

| Command Message | “Do this action” | Action will be performed | Execute the command |

| Event Message | “This happened” | None (it’s a broadcast) | React however you want (or ignore) |

These matter more than they might seem. The type you choose affects who’s responsible when things go wrong.

Document Message

A Document Message is a data carrier. The sender packages up information and ships it to the receiver. Think file transfers, data synchronization, or batch imports.

“Use a Document Message to reliably transfer a data structure between applications.”

Examples:

- An invoice with line items sent to an accounting system

- A product catalog update pushed to retail partners

- A user profile exported for GDPR compliance

Notice what’s different here: the sender cares that the data arrives, not what the receiver does with it. The document is self-contained. Everything needed is in the payload.

pub type InvoiceId { InvoiceId(String) }

pub type Money { Money(amount: Int, currency: String) }

pub type Invoice {

Invoice(

id: InvoiceId,

customer: Customer,

line_items: List(LineItem),

subtotal: Money,

tax: Money,

total: Money,

payment_terms: PaymentTerms,

)

}

pub fn export_invoice(invoice: Invoice, channel: Channel) -> Nil {

invoice

|> invoice_to_json

|> channel.send(channel, _)

}

Command Message

A Command Message is an imperative: a request for the receiver to do something specific.

“Use a Command Message to reliably invoke a procedure in another application.”

Examples:

CreateUser { email, name, role }ProcessPayment { orderId, amount, paymentMethod }SendNotification { userId, template, data }

Unlike documents, commands have expectations. The sender wants the action performed. Usually there’s a response: success, failure, or a result. If the command fails, someone needs to know.

pub type OrderId { OrderId(String) }

pub type CustomerId { CustomerId(String) }

pub type PlaceOrder {

PlaceOrder(

customer_id: CustomerId,

items: List(OrderLineItem),

shipping_address: ShippingAddress,

reply_to: String,

correlation_id: String,

)

}

pub type PlaceOrderResult {

OrderPlaced(order_id: OrderId, correlation_id: String)

OrderRejected(reason: String, correlation_id: String)

}

pub fn handle_place_order(cmd: PlaceOrder) -> Result(PlaceOrderResult, String) {

use order <- result.try(order_repository.create(cmd))

Ok(OrderPlaced(order.id, cmd.correlation_id))

}

The imperative naming (PlaceOrder, not OrderPlaced) signals intent. Commands are verb phrases that request action. Gleam’s Result type makes the response expectation explicit: commands can fail, and the caller needs to know. The reply_to and correlation_id fields enable Request-Reply conversations.

Event Message

An Event Message announces that something happened. It’s a fact, stated in the past tense, broadcast to whoever cares.

“Use an Event Message for reliable, asynchronous event notification between applications.”

Examples:

OrderPlaced { orderId, timestamp }UserRegistered { userId, email }PaymentFailed { orderId, reason }

Events are fundamentally different from commands:

| Aspect | Command | Event |

|---|---|---|

| Tense | Imperative (“do this”) | Past (“this happened”) |

| Expectation | Action required | No obligation |

| Failure | Must be handled | Receiver’s problem |

| Coupling | Sender knows receiver exists | Sender doesn’t care who listens |

pub type OrderId { OrderId(String) }

pub type CustomerId { CustomerId(String) }

pub type OrderEvent {

OrderPlaced(order_id: OrderId, customer_id: CustomerId, total: Money)

OrderShipped(order_id: OrderId, tracking_number: String)

OrderDelivered(order_id: OrderId, delivered_at: Time, signature: String)

}

pub fn publish(event: OrderEvent, event_bus: EventBus) -> Nil {

event_bus.publish(event)

}

The sender’s responsibility ends when the event is published. Zero, one, or a hundred consumers might react. The publisher doesn’t know and doesn’t care.

The Intent Triangle

Here’s a mental model for choosing:

Document: You’re throwing data over the wall. The receiver decides what to do with it.

Command: You need something done and you want to know if it worked.

Event: You’re announcing facts. Whoever cares can react.

Build It Yourself: Same Scenario, Three Message Types

Let’s see how the same business action looks as each message type:

Scenario: A customer places an order.

pub type OrderId { OrderId(String) }

pub type CustomerId { CustomerId(String) }

// Document: self-contained data for external partner

pub type OrderFulfillmentDocument {

OrderFulfillmentDocument(

order_id: OrderId,

customer: CustomerDetails,

line_items: List(LineItem),

totals: OrderTotals,

)

}

// Command: expects acknowledgment

pub type FulfillOrder {

FulfillOrder(

order_id: OrderId,

customer_id: CustomerId,

items: List(OrderLineItem),

reply_to: String,

correlation_id: String,

)

}

// Event: past-tense fact

pub type OrderPlaced {

OrderPlaced(order_id: OrderId, customer_id: CustomerId, occurred_at: Time)

}

As a Document Message:

pub fn export_for_fulfillment(order: Order, customer: Customer) -> Nil {

OrderFulfillmentDocument(

order_id: order.id,

customer: customer |> to_customer_details,

line_items: order.line_items,

totals: order.line_items |> calculate_totals,

)

|> fulfillment_partner.send

}

As a Command Message:

pub fn request_fulfillment(order: Order) -> Result(OrderId, FulfillmentError) {

let cmd = FulfillOrder(

order_id: order.id,

customer_id: order.customer_id,

items: order.line_items,

reply_to: "fulfillment-responses",

correlation_id: uuid.v4(),

)

case command_bus.send_and_wait(cmd, timeout_ms: 5000) {

Ok(FulfillmentAccepted(id, _)) -> Ok(id)

Ok(FulfillmentRejected(reason, _)) -> Error(reason)

Error(Timeout) -> Error(FulfillmentTimedOut)

}

}

An important distinction to make here is that while this example shows a synchronous command, commands can be completely asynchronous too. For example, the command recieved is executed and the result is sent to a notification channel, which in turn maybe sends out an email or invokes some other process that should handle the result. There are a lot of ways you can mix and compose different message patterns throughout the system.

As an Event:

pub fn publish_order_placed(order: Order) -> Nil {

OrderPlaced(order.id, order.customer_id, birl.now())

|> event_bus.publish

// Inventory, Notifications, Analytics, Fraud all react independently

}

The event approach enables the most decoupling. The order service publishes once; any number of systems react independently.

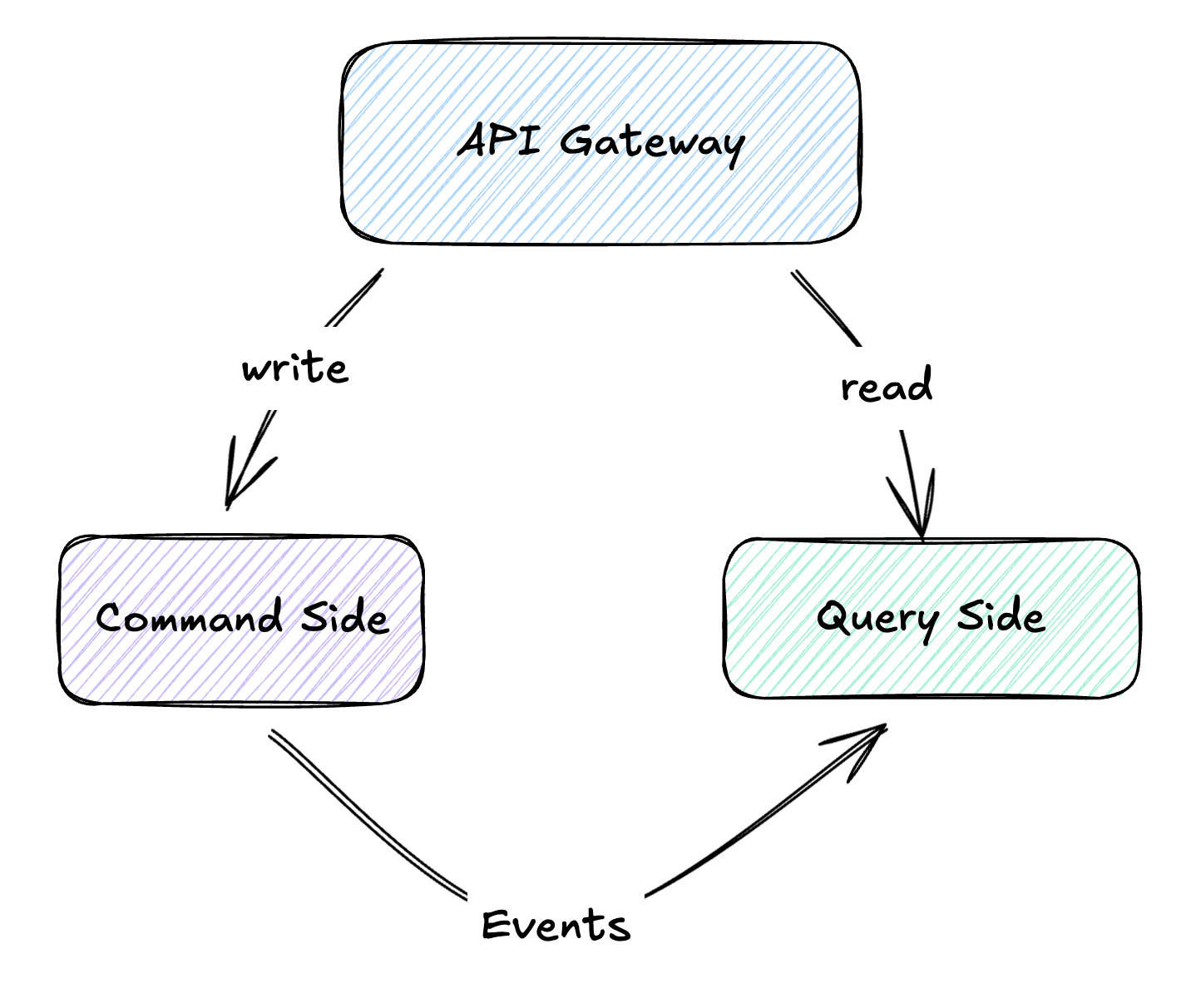

CQRS: Commands and Events as Architecture

Once you start thinking in commands and events, you’re already halfway to CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation).

The idea: separate the write path from the read path.

Commands flow to the write model, where business logic validates and processes them. When state changes, events are published. Read models subscribe to these events and build optimized views for querying.

Why bother? Because reads and writes have fundamentally different needs. Your write model cares about validation and consistency: is this order valid? does this customer have enough credit? Your read model cares about speed: show me all orders for customer X, sorted by date, with their current status.

A practical example:

Your e-commerce site processes 100 orders per minute but handles 10,000 product searches per second. With CQRS:

- Write side: Validates orders, manages inventory, processes payments. Needs ACID transactions. Might use PostgreSQL.

- Read side: Serves product catalogs, search results, recommendations. Optimized for speed. Might use Elasticsearch or Redis.

Events bridge the gap. When inventory changes on the write side, an InventoryUpdated event propagates to update the search index.

pub type ProductId { ProductId(String) }

pub type ReserveStock {

ReserveStock(product_id: ProductId, quantity: Int)

}

pub type InventoryEvent {

StockReserved(product_id: ProductId, reserved: Int, available: Int)

StockReservationFailed(product_id: ProductId, reason: String)

}

// Write side: handle command, emit event

pub fn handle_reserve_stock(

cmd: ReserveStock,

inventory_repository: InventoryRepository,

event_bus: EventBus,

) -> Result(Nil, InventoryError) {

use item <- result.try(inventory_repository.find(cmd.product_id))

case item.available >= cmd.quantity {

False -> Error(InsufficientStock(cmd.product_id, item.available))

True -> {

let remaining = item.available - cmd.quantity

use _ <- result.try(inventory_repository.reserve(cmd.product_id, cmd.quantity))

StockReserved(cmd.product_id, cmd.quantity, remaining)

|> event_bus.publish

Ok(Nil)

}

}

}

// Read side: update search index

pub fn on_stock_reserved(event: InventoryEvent, search: ProductSearchIndex) -> Nil {

let StockReserved(product_id, _, available) = event

search.update(product_id, [

#("available", json.int(available)),

#("in_stock", json.bool(available > 0)),

])

}

You probably don’t need CQRS for most applications. It adds real complexity. But when you’re serving 100x more reads than writes, or when your read models need to look completely different from your write models, it earns its keep.

The Payload Spectrum

Okay, so events announce facts. But how fat should they be? This is where you’ll get into arguments.

Consider OrderPlaced. It could be:

Minimal (Event Notification):

{ "type": "OrderPlaced", "orderId": "ord-123" }

Maximal (Event-Carried State Transfer):

{

"type": "OrderPlaced",

"orderId": "ord-123",

"customer": { "id": "cust-456", "name": "Alice", "email": "alice@example.com", "tier": "gold" },

"items": [

{ "sku": "WIDGET-A", "name": "Blue Widget", "quantity": 2, "price": 29.99 },

{ "sku": "GADGET-B", "name": "Red Gadget", "quantity": 1, "price": 49.99 }

],

"shipping": { "address": "123 Main St", "method": "express", "cost": 12.99 },

"totals": { "subtotal": 109.97, "tax": 9.90, "shipping": 12.99, "total": 132.86 }

}

Both are valid. The right choice depends on who’s consuming the event and what they need to do with it.

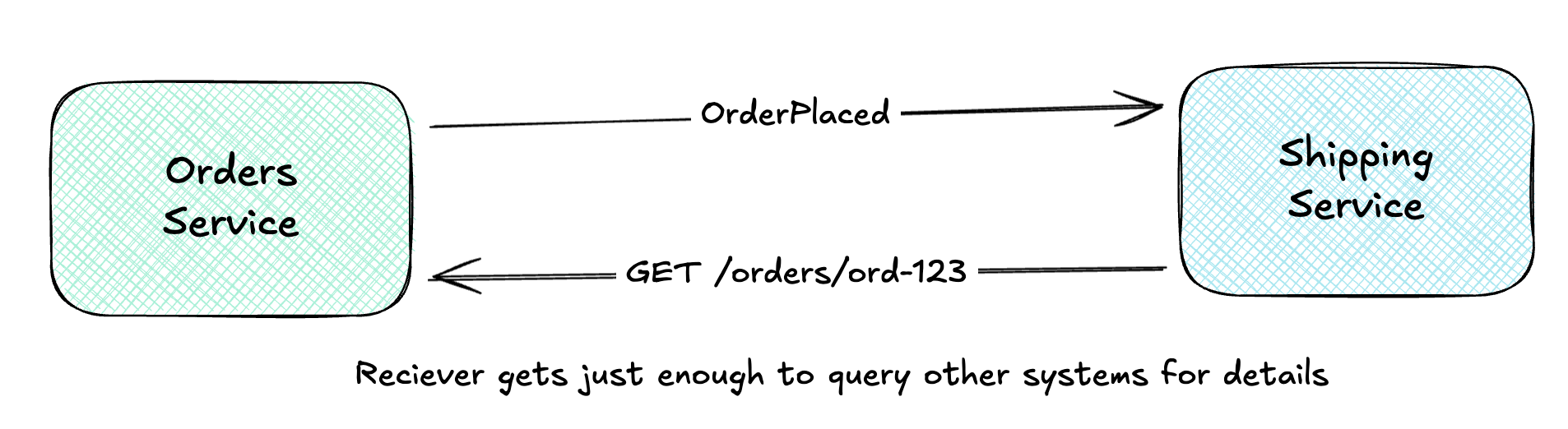

Event Notification (Thin Events)

The Event Notification pattern uses minimal payloads. The event says what happened, not everything about it.

The consumer receives the notification, then queries the source (or other sources) for details.

Pros:

- Small event payloads, easy to transmit

- Source remains the authority, data is always fresh

- Privacy-friendly: sensitive data isn’t broadcast

- Schema evolution is easier (less to change)

Cons:

- Coupling: consumer must know how to query the source

- Latency: synchronous call adds round-trip time

- Availability: if source is down, consumer is stuck

- Load: popular events trigger many queries

pub type OrderId { OrderId(String) }

pub type OrderPlaced {

OrderPlaced(order_id: OrderId)

}

pub fn on_order_placed(

event: OrderPlaced,

order_repository: OrderRepository,

) -> Result(Shipment, ShippingError) {

// Must query for details, event only has the ID

use order <- result.try(order_repository.find(event.order_id))

order

|> shipment.create

}

Thin events work well when data changes often (you want freshness), when payloads would otherwise be huge, or when privacy regulations make you nervous about broadcasting customer data across your infrastructure.

Event-Carried State Transfer (Fat Events)

Event-Carried State Transfer takes the opposite approach: events carry all the data consumers need.

But here’s the key insight most people miss: ECTS isn’t just about fat events. It’s about building local replicas.

The Shipping Service:

- Receives events with complete order data

- Stores relevant data in its own database

- Queries its local store, never calls back to Orders

This enables query autonomy. The Shipping Service can answer “what’s the shipping address for order 123?” without any network call. Even if the Orders Service is down for maintenance, Shipping keeps working.

Pros:

- Consumer autonomy: no callbacks to source

- Resilience: source can go offline

- Performance: local queries are fast

- Consumers can structure data for their needs

Cons:

- Larger events consume more bandwidth

- Eventual consistency: local data may be stale

- Duplication: same data lives in multiple places

- Privacy concerns: data spreads across systems

pub type OrderId { OrderId(String) }

pub type OrderPlaced {

OrderPlaced(

order_id: OrderId,

customer: CustomerSnapshot,

shipping: ShippingDetails,

line_items: List(OrderLineItem),

)

}

// Local read model, structured for shipping queries

pub type ShippableOrder {

ShippableOrder(

order_id: OrderId,

customer_name: String,

shipping_address: String,

items: List(OrderLineItem),

)

}

pub fn on_order_placed(event: OrderPlaced, cache: OrderCache) -> Result(Nil, CacheError) {

let shippable = ShippableOrder(

order_id: event.order_id,

customer_name: event.customer.name,

shipping_address: event.shipping.address,

items: event.line_items,

)

use _ <- result.try(cache.store(event.order_id, shippable))

event.order_id

|> shipment.schedule

}

pub fn get_shipping_label(order_id: OrderId, cache: OrderCache) -> Result(ShippingLabel, ShippingError) {

// Query local cache, no call to Orders service

use order <- result.try(cache.find(order_id))

order

|> shipping_label.generate

}

ECTS shines when your consumers repeatedly query the same data, when you want services that keep working even when their upstream dependencies are down, or when you’ve made peace with eventual consistency (which, honestly, you probably should).

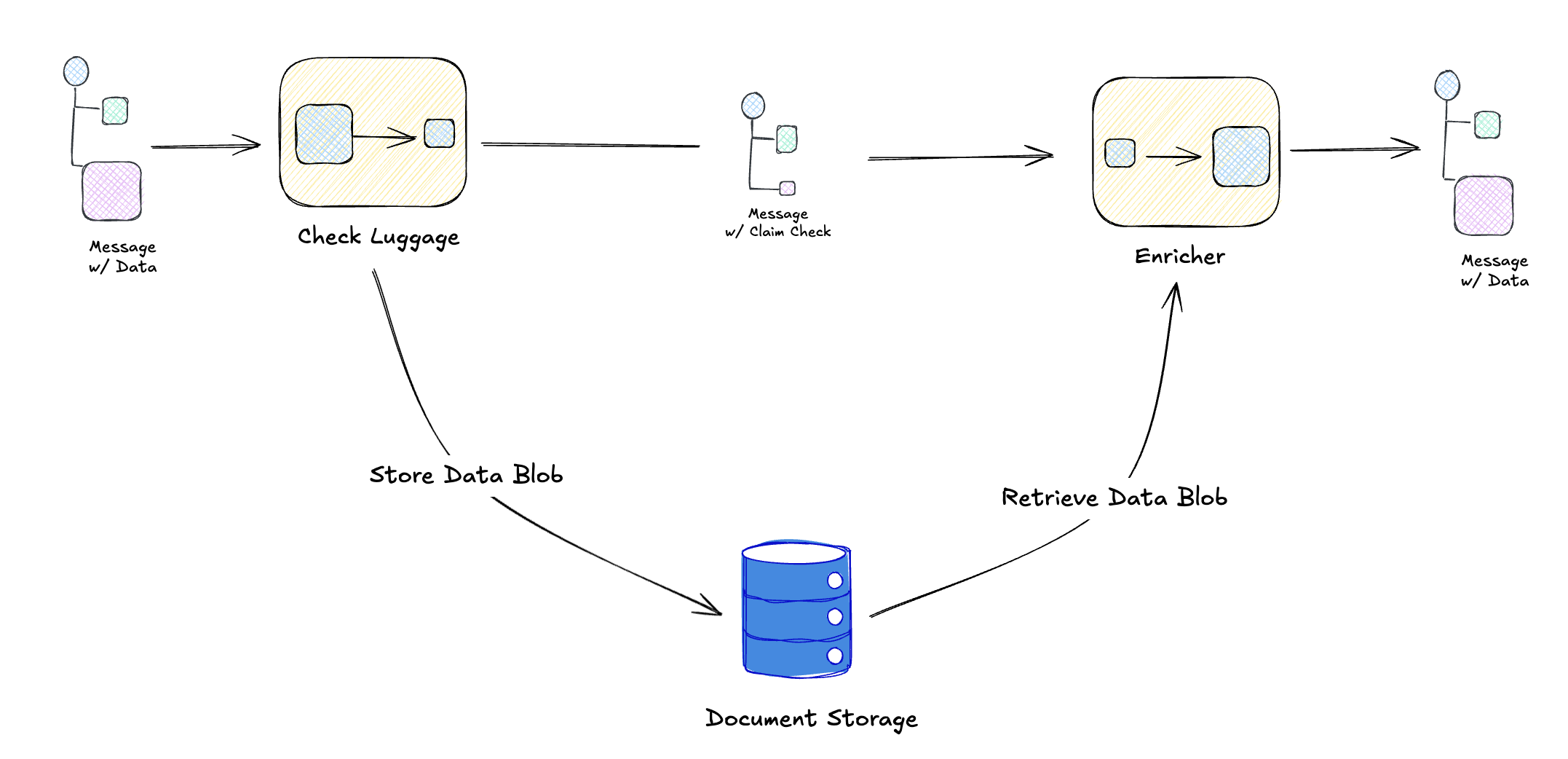

Claim Check Pattern

What if you want thin events but have large payloads? The Claim Check pattern is your friend.

“Store message data in persistent storage and pass a Claim Check to subsequent components, which use the Claim Check to retrieve the stored information.”

Think of it like checking a coat at a restaurant. You get a small ticket (the claim check), not the coat itself. When you need the coat, you present the ticket.

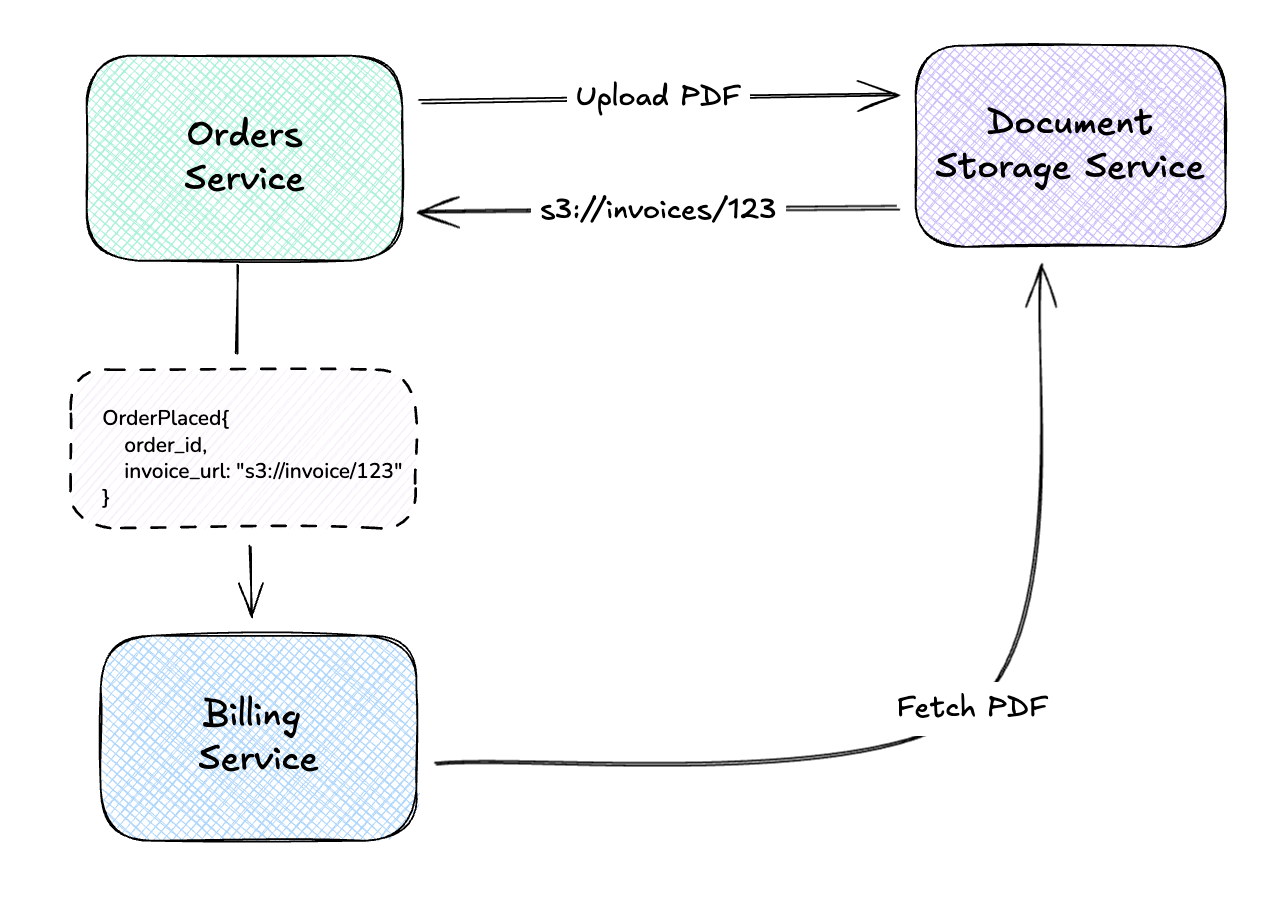

And to see this in a practical example, we might have an Orders Service that uploads a document to s3, emits an OrderPlaced event that one of the consumers might fetch and attach to an order confirmation email being sent out.

The event stays small (just a reference), but consumers can fetch the full payload when needed.

Perfect for:

- Large attachments (PDFs, images, documents)

- Data that not all consumers need

- Payloads that would bloat your message broker

- Compliance scenarios where data must live in specific storage

# Claim Check pattern

import boto3

class OrderService:

def __init__(self):

self.s3 = boto3.client('s3')

self.events = EventBus()

def place_order(self, order: Order) -> None:

# Generate and store the large document

invoice_pdf = self.generate_invoice_pdf(order)

invoice_key = f"invoices/{order.id}.pdf"

self.s3.put_object(

Bucket="order-documents",

Key=invoice_key,

Body=invoice_pdf,

)

# Event carries just the claim check (reference)

self.events.publish("OrderPlaced", {

"orderId": order.id,

"invoiceUrl": f"s3://order-documents/{invoice_key}", # Claim check!

"invoiceSizeBytes": len(invoice_pdf),

})

class BillingService:

def on_order_placed(self, event: dict):

# Fetch the document using the claim check

invoice_pdf = self.s3.get_object(

Bucket="order-documents",

Key=event["invoiceUrl"].replace("s3://order-documents/", ""),

)["Body"].read()

self.archive_invoice(event["orderId"], invoice_pdf)

Choosing a Payload Strategy

| Strategy | Event Size | Consumer Autonomy | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Event Notification | Tiny | Low (queries source) | Fresh data, privacy, simple events |

| Event-Carried State | Large | High (local replica) | Autonomous services, resilience |

| Claim Check | Tiny + ref | Medium (fetches blob) | Large attachments, documents |

You can mix these. A single event might carry essential fields inline (Event-Carried State), reference a PDF via claim check, and leave rarely-needed details for consumers to query on demand.

Representing State Changes

When something changes, how do you capture that in an event? You’ve got options:

Delta Events (What Changed)

A delta event contains only the fields that changed:

{

"type": "UserUpdated",

"userId": "user-123",

"changes": {

"email": "newemail@example.com",

"role": "admin"

}

}

Pros:

- Compact: only changed fields transmitted

- Clear what actually changed

- Good for audit trails (“field X was modified”)

Cons:

- Consumers need prior state to reconstruct current state

- Ordering matters: apply deltas in sequence

- Complex for deeply nested changes

import gleam/dict

import gleam/list

pub type UserId { UserId(String) }

pub type UserProfileChanged {

UserProfileChanged(user_id: UserId, changes: List(ProfileChange))

}

pub type ProfileChange {

EmailChanged(old: String, new: String)

RoleAssigned(role: String)

RoleRevoked(role: String)

}

pub fn apply_profile_changes(

event: UserProfileChanged,

users: dict.Dict(UserId, User),

) -> Result(dict.Dict(UserId, User), String) {

case dict.get(users, event.user_id) {

Error(Nil) -> Error("User not found")

Ok(existing) -> {

let updated = list.fold(event.changes, existing, fn(user, change) {

case change {

EmailChanged(_, new) -> User(..user, email: new)

RoleAssigned(role) -> User(..user, role: role)

RoleRevoked(_) -> User(..user, role: "none")

}

})

Ok(dict.insert(users, event.user_id, updated))

}

}

}

Deltas are great for audit trails (“field X changed from A to B”) and when bandwidth matters. The catch: consumers need to track state to make sense of them.

Full-State Events (Complete Snapshot)

A full-state event contains the complete entity after the change:

{

"type": "UserUpdated",

"userId": "user-123",

"user": {

"id": "user-123",

"name": "Alice Smith",

"email": "newemail@example.com",

"role": "admin",

"createdAt": "2024-01-15T10:00:00Z",

"lastLogin": "2025-12-22T14:30:00Z"

}

}

Pros:

- Consumers don’t need prior state

- Easy to build projections: just overwrite

- Ordering less critical (latest snapshot wins)

- Simpler consumer logic

Cons:

- Larger payloads

- Unclear what specifically changed

- Potential for stale data if events arrive out of order

import gleam/dict

pub type UserId { UserId(String) }

pub type UserUpdated {

UserUpdated(user_id: UserId, user: User)

}

pub type User {

User(

id: UserId,

email: String,

name: String,

role: String,

created_at: Time,

last_login: Time,

)

}

pub fn apply_user_snapshot(

event: UserUpdated,

users: dict.Dict(UserId, User),

) -> dict.Dict(UserId, User) {

// Just overwrite, no prior state needed

dict.insert(users, event.user_id, event.user)

}

Full-state events are dead simple for consumers. Just overwrite whatever you had. Perfect for search indexes, read model projections, or any situation where a consumer might have missed events and needs to catch up.

Enriched Events (Context Included)

Enriched events include not just the entity, but related context:

{

"type": "OrderPlaced",

"orderId": "ord-789",

"order": {

"id": "ord-789",

"status": "placed",

"placedAt": "2025-12-22T15:00:00Z"

},

"customer": {

"id": "cust-456",

"name": "Alice Smith",

"tier": "gold",

"lifetimeValue": 15420.00

},

"context": {

"channel": "mobile-app",

"campaign": "holiday-2025",

"abTestVariant": "checkout-v2"

}

}

The event carries denormalized data from related entities: the customer details, the marketing context, etc.

Pros:

- Self-contained: consumers have full picture

- No joins required

- Great for analytics and reporting

Cons:

- Data duplication across events

- Stale if related entities change

- Larger payloads

- Coupling to related entity schemas

This is essentially Event-Carried State Transfer applied at enrichment time. The trade-off is the same: autonomy versus freshness.

Remember from Day 2 when we discussed enriching at read time vs. write time? The same principle applies here:

- Write-time enrichment: Bake context into the event. Consumers get a snapshot frozen at event time.

- Read-time enrichment: Store references, hydrate when queried. Consumers get current data.

Pick based on whether you care more about the world as it was when the event happened, or the world as it is now.

Putting It All Together

Here’s how this plays out in practice: an e-commerce order with multiple consumers, each caring about different parts of the same event.

Each consumer pulls what it needs from the same event:

Inventory Service

When OrderPlaced arrives, Inventory grabs the items array and reserves stock. It maintains its own inventory counts locally. No need to ask anyone else “how many widgets do we have left?”

Shipping Service

Shipping cares about where the package is going. It extracts the customer address and line items, queues up a shipment, and never calls back to Orders. If the Orders service goes down for maintenance, Shipping keeps processing its queue.

Analytics Service

Analytics wants everything: not just the order, but the context around it. Which campaign drove this purchase? What tier is this customer? Is this a mobile or web checkout? The enriched event gives them a complete picture for their data warehouse without joining across services.

The event design:

{

"type": "OrderPlaced",

"occurredAt": "2025-12-22T15:30:00Z",

"orderId": "ord-abc123",

"order": {

"id": "ord-abc123",

"items": [

{ "sku": "WIDGET-A", "quantity": 2, "price": 29.99 }

],

"totals": { "subtotal": 59.98, "tax": 5.40, "total": 65.38 }

},

"customer": {

"id": "cust-xyz",

"tier": "gold"

},

"shipping": {

"address": "123 Main St, Anytown, ST 12345",

"method": "standard"

},

"context": {

"channel": "web",

"campaign": "holiday-2025"

},

"attachments": {

"invoiceUrl": "s3://orders/ord-abc123/invoice.pdf"

}

}

One event, four consumers, each grabbing the slice they care about. The invoice PDF uses Claim Check. Only Billing bothers to fetch it.

What Should You Actually Use?

My honest advice? Start simple. Event Notification is the path of least resistance: small events, consumers query when they need more. You avoid duplicating data, you avoid stale caches, you avoid the “which version of customer is this?” headaches.

But you’ll feel the pain eventually. That third service that needs order details and keeps hammering your API? That’s when Event-Carried State Transfer starts looking attractive. Let consumers build their own caches. Yes, data gets duplicated. Yes, it’s eventually consistent. But now your services can survive each other’s outages.

And when someone asks “can we attach the 5MB invoice PDF to the event?” That’s your cue for Claim Check. Keep your message broker happy by staying within message size constraints. Aside from that, it’s a good practice as some downstream consumers may not even need the PDF, allowing it to be loaded on demand in those who do need it.

What’s Next

We’ve covered the fundamentals: channels, routing, and message types. Tomorrow we’ll explore Message Transformation patterns, covering how to reshape, enrich, and normalize messages as they flow through your system:

- Content Enricher: Adding data from external sources

- Content Filter: Removing unnecessary fields

- Normalizer: Converting diverse formats to a canonical form

- Canonical Data Model: A shared vocabulary across systems

These patterns complete the picture: you can route messages, but often you need to transform them for different consumers.

See you on Day 6! 🎄

This post is part of the Advent of Enterprise Integration Patterns series. Check out the introduction or follow along with the enterprise-integration-patterns tag. All patterns referenced are from the classic book Enterprise Integration Patterns by Gregor Hohpe and Bobby Woolf.

A note on process: I used Claude Opus 4.5 to help organize the patterns into logical groupings, generate the summary tables, and structure the code examples. The concepts and opinions are mine, informed by the sources cited and practical experience.