Previously on Advent of Enterprise Integration Patterns: in Day 3, we explored message channels: Point-to-Point, Publish-Subscribe, Datatype, and Invalid Message channels. We built them first in pure code, then mapped them to RabbitMQ and Kafka as examples.

Today we’re stepping away from Chronicle to focus purely on patterns. Chronicle needs some housekeeping (the boring-but-essential work of making it a proper audit logging system), and frankly, that’s a good thing. Don’t set out to implement every pattern in a system. Patterns are tools for specific problems. Nothing is worse than a pattern that feels forced.

So today we’ll explore four Message Routing patterns on their own terms. These answer a simple question: once a message is in the system, where does it go next?

Channel types determine delivery semantics (who receives a message). Routing patterns determine message flow (which path it takes). Channels are the pipes; routing patterns are the valves and junctions.

The Four Routing Patterns

Today’s patterns form a toolkit for controlling message flow:

| Pattern | What It Does | Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| Content-Based Router | Routes to different destinations based on message content | Mail sorter reading zip codes |

| Message Filter | Drops messages that don’t match criteria | Spam filter |

| Splitter | Breaks one message into many | Unpacking a box of items |

| Aggregator | Combines many messages into one | Assembling a care package |

Each pattern solves a distinct problem. Often you’ll combine them—a Content-Based Router might send messages to a Splitter, which fans out to Filters, which feed into an Aggregator. Let’s understand each one first.

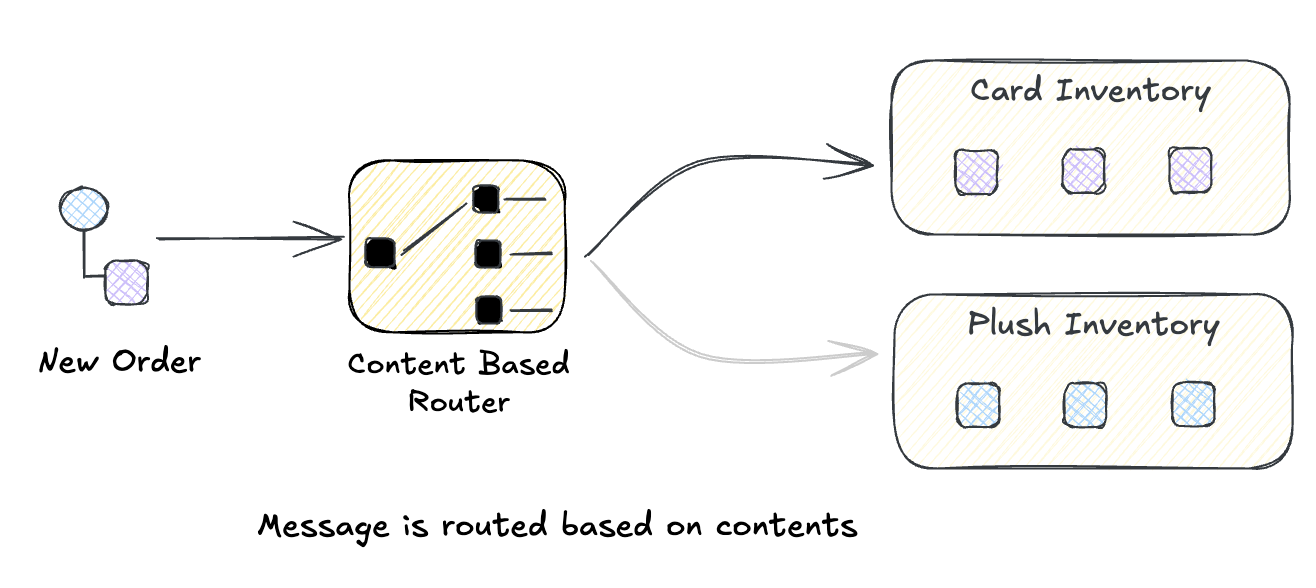

Content-Based Router

You’ve seen this pattern before, even if you didn’t call it that. Every time you write if message.type == "order" and send it one place versus another—that’s a Content-Based Router.

The idea is simple: peek inside the message, figure out what it is, and send it where it needs to go. Orders from the West Coast go to the California warehouse. High-priority support tickets go to the senior team. Payments via Stripe go to the Stripe handler.

What makes it a pattern rather than just an if-statement? The router itself doesn’t process the message—it only decides where it goes. This separation keeps your routing logic clean and your processing logic focused. Add a new destination? Update the router. Change how orders are processed? Update the handler. Neither knows about the other.

You’ll reach for this when:

- Different message types need different handlers (orders vs. returns vs. refunds)

- Business rules determine routing (VIP customers get the fast lane)

- You’re integrating multiple downstream systems and need to fan out intelligently

- Your single consumer is turning into a mess of

if/elsebranches

Build It Yourself: Python

A Content-Based Router is fundamentally a lookup or match. Here’s a rather naive example that takes an incoming Order object and routes it to the appropriate function, or handler, based on its region with a default handler for unrecognized regions.

from dataclasses import dataclass

from typing import Callable, Any

@dataclass

class Order:

id: str

region: str

priority: str

items: list

# Define handlers for different routes

def handle_us_order(order: Order):

print(f"📦 US Fulfillment: Processing order {order.id}")

def handle_eu_order(order: Order):

print(f"📦 EU Fulfillment: Processing order {order.id}")

def handle_apac_order(order: Order):

print(f"📦 APAC Fulfillment: Processing order {order.id}")

def handle_unknown(order: Order):

print(f"⚠️ Unknown region '{order.region}' for order {order.id}")

# The Content-Based Router

class ContentBasedRouter:

def __init__(self):

self.routes: dict[str, Callable] = {}

self.default_route: Callable = lambda x: None

def when(self, condition: str, handler: Callable) -> "ContentBasedRouter":

"""Add a route for a specific condition value."""

self.routes[condition] = handler

return self

def otherwise(self, handler: Callable) -> "ContentBasedRouter":

"""Set the default route for unmatched messages."""

self.default_route = handler

return self

def route(self, message: Any, key_extractor: Callable[[Any], str]):

"""Route a message based on extracted key."""

key = key_extractor(message)

handler = self.routes.get(key, self.default_route)

handler(message)

# Configure the router

router = (

ContentBasedRouter()

.when("US", handle_us_order)

.when("EU", handle_eu_order)

.when("APAC", handle_apac_order)

.otherwise(handle_unknown)

)

# Route some orders

orders = [

Order("ord-1", "US", "normal", ["widget"]),

Order("ord-2", "EU", "high", ["gadget", "gizmo"]),

Order("ord-3", "APAC", "normal", ["thing"]),

Order("ord-4", "LATAM", "low", ["stuff"]), # Unknown region

]

for order in orders:

router.route(order, key_extractor=lambda o: o.region)

Run this we see each message handled by the appropriate fulfillment center.

📦 US Fulfillment: Processing order ord-1

📦 EU Fulfillment: Processing order ord-2

📦 APAC Fulfillment: Processing order ord-3

⚠️ Unknown region 'LATAM' for order ord-4

The router doesn’t know or care what handlers do. It just matches and delegates. This is a lot like how it is handled in messaging systems as well. The messaging system doesn’t know about the details of the handlers, it just does a dumb match and routes to the appropriate destination. That’s it. Let’s take a look how RabbitMQ handles this.

RabbitMQ: Multiple Routing Strategies

RabbitMQ offers several exchange types for Content-Based Routing, each with different matching semantics:

Topic Exchanges — Route by routing key patterns:

Message with routing key "order.us.high" matches:

- "order.#" → All order handlers

- "order.us.*" → US fulfillment

- "*.*.high" → High priority queue

- "#" → Catch-all analytics

The routing key is typically set by the producer based on message content. This is fast (string matching) but limited—you can only route on what’s encoded in the routing key.

Headers Exchanges — Route by message headers (true content-based routing):

Using pika, the Python RabbitMQ client:

# Producer sets headers based on message content

channel.basic_publish(

exchange='orders',

routing_key='', # Ignored for headers exchange

properties=pika.BasicProperties(

headers={

'region': 'US',

'priority': 'high',

'customer_tier': 'enterprise',

'order_value': 'large', # Derived from inspecting order total

}

),

body=json.dumps(order)

)

Queues bind with header matching rules:

# Bind queue with header matching

channel.queue_bind(

exchange='orders',

queue='vip_orders',

arguments={

'x-match': 'all', # 'all' = AND, 'any' = OR

'customer_tier': 'enterprise',

'order_value': 'large',

}

)

Headers exchanges inspect actual message metadata, not just routing keys. The trade-off is performance—header matching is slower than topic matching. The “VIP Fast Lane” is a kind of pattern in itself that I have seen at various companies. Higher tier customers get processing priority with queues that have more consumers and processing power.

Kafka Connect: Content-Based Routing with SMTs

Kafka Connect uses Single Message Transforms (SMTs) to implement Content-Based Routing. SMTs inspect and modify messages in-flight:

{

"name": "order-router",

"config": {

"connector.class": "io.confluent.connect.kafka.KafkaSinkConnector",

"topics": "orders",

"transforms": "routeByRegion",

"transforms.routeByRegion.type": "org.apache.kafka.connect.transforms.RegexRouter",

"transforms.routeByRegion.regex": "orders",

"transforms.routeByRegion.replacement": "orders-${topic.region}"

}

}

For more complex routing, you can chain SMTs or use custom transforms that parse JSON payloads:

{

"transforms": "extractRegion,routeByValue",

"transforms.extractRegion.type": "org.apache.kafka.connect.transforms.ExtractField$Value",

"transforms.extractRegion.field": "region",

"transforms.routeByValue.type": "io.confluent.connect.transforms.TopicRoutingByField",

"transforms.routeByValue.field.name": "region",

"transforms.routeByValue.topic.format": "orders-${field}"

}

This routes messages to different topics based on the region field in the JSON payload:

{"region": "US", ...}→orders-US{"region": "EU", ...}→orders-EU

Kafka Streams provides even more flexibility for content-based routing with full access to message content:

KStream<String, Order> orders = builder.stream("orders");

// Route by inspecting message content

orders.split()

.branch((key, order) -> order.getTotal() > 10000,

Branched.withConsumer(s -> s.to("high-value-orders")))

.branch((key, order) -> order.getRegion().equals("EU"),

Branched.withConsumer(s -> s.to("eu-orders")))

.defaultBranch(Branched.withConsumer(s -> s.to("standard-orders")));

This is true content-based routing—inspecting the order total and region fields to determine the destination topic.

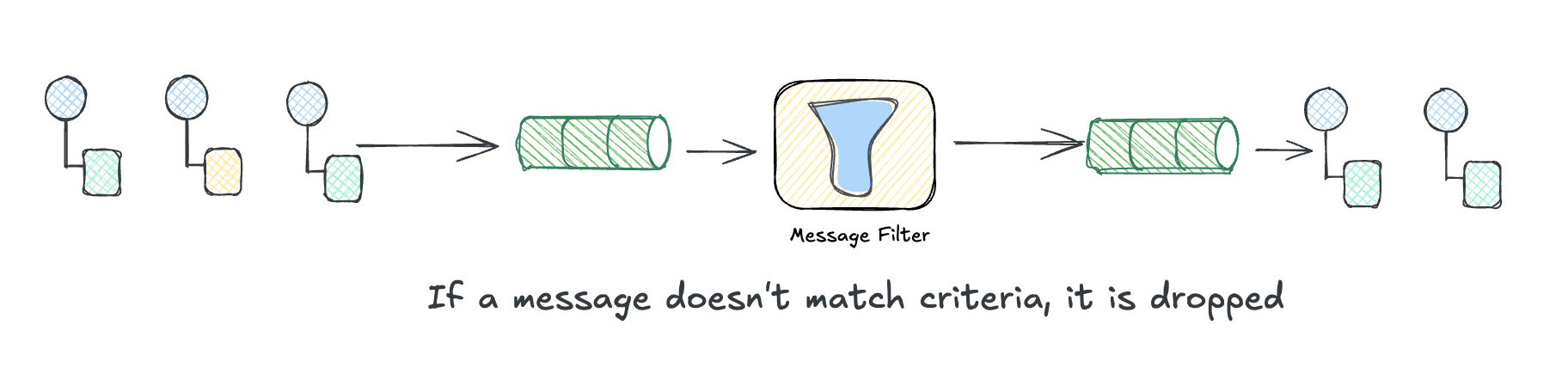

Message Filter

If a Content-Based Router is an if-else, a Message Filter is just the if part with no else. The message either passes through or it disappears.

This comes up constantly. Your analytics pipeline doesn’t need health check pings. Your billing system shouldn’t see test accounts. Your third-party integrations shouldn’t receive PII. Instead of making every downstream consumer deal with filtering out junk, you put a filter at the source and let only the relevant messages through.

The filter itself is dead simple: it’s a predicate. Return true, the message continues. Return false, it’s gone. No routing decision, no alternative destination. Just pass or drop.

Build It Yourself: Message Filter

It’s literally just .filter() with a predicate:

const { EventEmitter } = require("events");

type Log = { level: string; message: string; synthetic: boolean };

const bus = new EventEmitter();

// The filter: only real errors pass through

bus.on("log", (log: Log) => {

if (log.level === "error" && !log.synthetic) {

bus.emit("alert", log);

}

});

// Downstream handler

bus.on("alert", (log: Log) => console.log(`🚨 ALERT: ${log.message}`));

// Simulate messages arriving over time

const incoming: Log[] = [

{ level: "info", message: "User signed in", synthetic: false },

{ level: "error", message: "Payment failed", synthetic: false },

{ level: "error", message: "Health check", synthetic: true },

];

const interval = setInterval(() => {

const log = incoming.shift();

if (!log) return clearInterval(interval);

console.log(`→ Received: ${log.message}`);

bus.emit("log", log);

}, 100);

// Output:

// → Received: User signed in

// → Received: Payment failed

// 🚨 ALERT: Payment failed

// → Received: Health check

Three messages arrive, one passes the filter. The “Health check” error had synthetic: true, so it got dropped—we only want real production issues hitting PagerDuty.

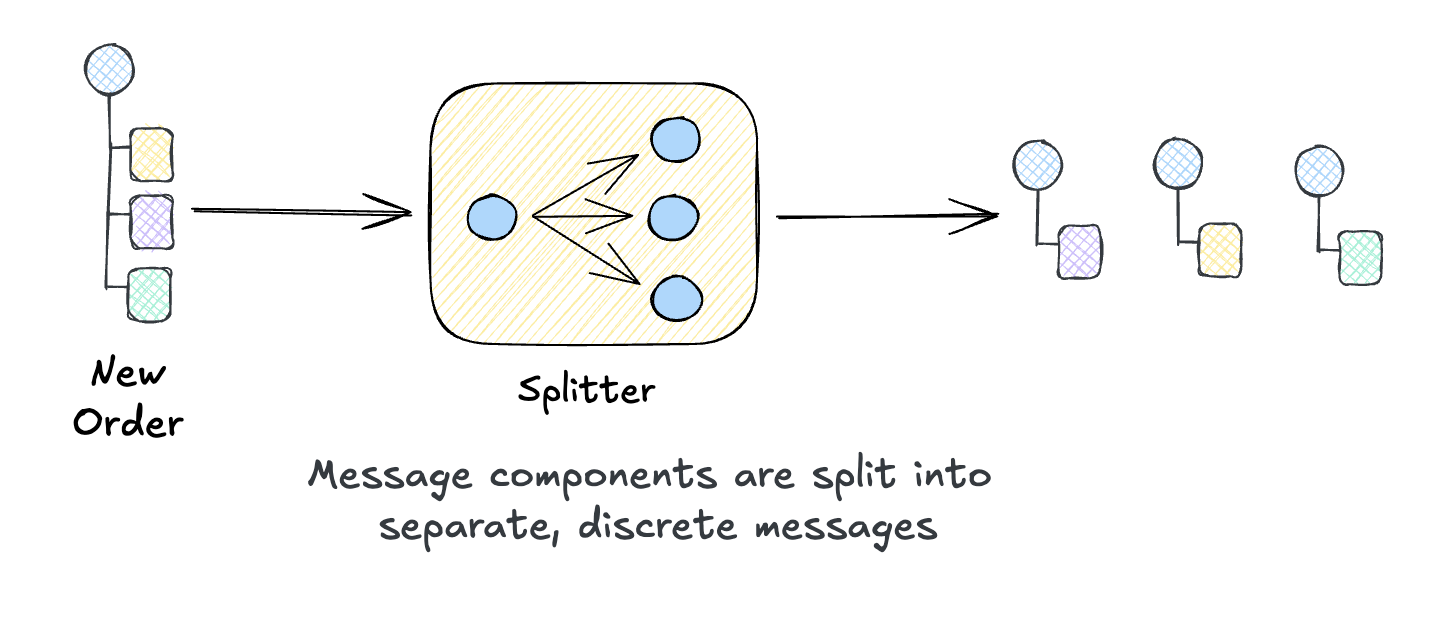

Splitter

The Splitter pattern breaks a single message into multiple messages:

“Use a Splitter to break out the composite message into a series of individual messages, each containing data related to one item.”

Think of an order with multiple line items. Do you want one consumer to handle the entire order, or do you want separate consumers to handle each item independently? A Splitter enables the latter, splitting a larger message into logical chunks to be processed independently.

When to use it:

- A message contains a collection that should be processed item-by-item

- Different items need different processing paths

- You want parallel processing of items

Examples:

- Split an order into individual line items for fulfillment

- Break a file upload into individual records for processing

- Expand a batch API request into individual operations

Build It Yourself

Gleam’s functional style makes splitters elegant—it’s essentially list.index_map with context:

import gleam/io

import gleam/list

import gleam/int

pub type Order { Order(id: String, items: List(String)) }

pub type ItemMsg { ItemMsg(order_id: String, item: String, index: Int, total: Int) }

pub fn split(order: Order) -> List(ItemMsg) {

let total = list.length(order.items)

use item, i <- list.index_map(order.items)

ItemMsg(order.id, item, i, total)

}

pub fn main() {

Order("ORD-123", ["Widget", "Gadget", "Gizmo"])

|> split

|> list.each(fn(msg) {

io.println("[" <> int.to_string(msg.index + 1) <> "/" <> int.to_string(msg.total) <> "] " <> msg.item)

})

}

// Output:

// [1/3] Widget

// [2/3] Gadget

// [3/3] Gizmo

// Output:

// Splitting order ORD-12345 into fulfillment requests:

// [1/3] WIDGET-A x2

// [2/3] GADGET-B x1

// [3/3] GIZMO-C x3

Notice each split message carries the original order_id. In messaging terms, this is a correlation identifier. It ties related messages back to a common root so you can trace an entire conversation.

You might also include a causation ID, which is the ID of the message that directly spawned this one. The rule is simple: when you create a new message in response to another, copy the parent’s correlation ID and set its message ID as your causation ID. This lets you follow the chain of what caused what.

Why bother? When something fails three services deep, you’ll want to trace it back: “This fulfillment error came from item 2 of order ORD-123, which was split from the original checkout request.” Correlation and causation IDs make that possible without digging through logs.

Splitter + Router: A Powerful Combination

Splitters often pair with Content-Based Routers. Split the order, then route each item to the appropriate fulfillment system:

Order (3 items)

│

▼

[Splitter]

│

├── Item 1 (electronics) ──→ [Router] ──→ Electronics Warehouse

├── Item 2 (books) ──→ [Router] ──→ Book Fulfillment

└── Item 3 (clothing) ──→ [Router] ──→ Apparel Center

Each item takes a different path based on its category. The Splitter enables this per-item routing.

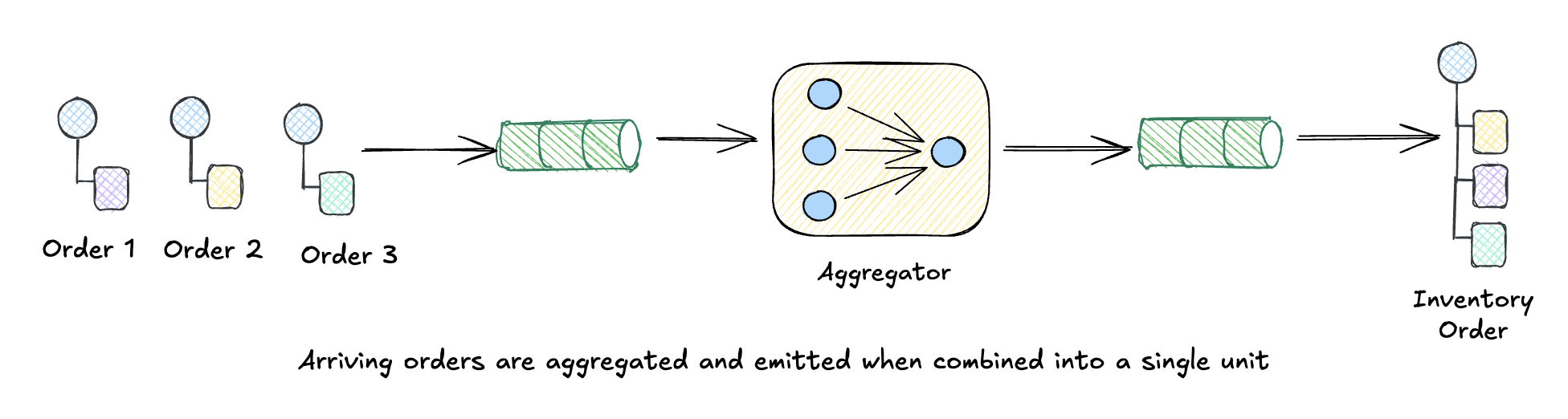

Aggregator

If Splitter breaks things apart, Aggregator puts them back together. It collects related messages and combines them into a single result.

This is the trickiest routing pattern because it’s stateful. An Aggregator has to answer four questions:

- Which messages belong together? (That’s where correlation IDs earn their keep)

- What have we received so far? (State has to live somewhere)

- Are we done yet? (Count-based? Timeout? Special “last message” marker?)

- What do we emit? (Sum? List? Some computed result?)

You’ll reach for an Aggregator when you need to collect shipping quotes from multiple carriers, combine search results from different backends, or reassemble those order items after they’ve been processed in parallel.

Build It Yourself: TypeScript

An aggregator is just a Map that collects messages until a group is complete:

type Quote = { orderId: string; carrier: string; price: number };

const pending = new Map<string, Quote[]>();

const CARRIERS = ["fedex", "ups", "usps"];

function addQuote(quote: Quote) {

// Get or create bucket for this order

if (!pending.has(quote.orderId)) pending.set(quote.orderId, []);

pending.get(quote.orderId)!.push(quote);

const quotes = pending.get(quote.orderId)!;

console.log(` ${quote.carrier} for ${quote.orderId} (${quotes.length}/${CARRIERS.length})`);

// Complete when all carriers have responded

if (quotes.length === CARRIERS.length) {

pending.delete(quote.orderId);

const best = quotes.reduce((a, b) => (a.price < b.price ? a : b));

console.log(` ✅ Complete! Best: ${best.carrier} @ $${best.price}\n`);

}

}

// Quotes arrive out of order, for different orders

addQuote({ orderId: "ORD-100", carrier: "fedex", price: 12.99 });

addQuote({ orderId: "ORD-100", carrier: "usps", price: 8.99 });

addQuote({ orderId: "ORD-200", carrier: "ups", price: 15.99 });

addQuote({ orderId: "ORD-100", carrier: "ups", price: 14.99 }); // Completes!

// Output:

// fedex for ORD-100 (1/3)

// usps for ORD-100 (2/3)

// ups for ORD-200 (1/3)

// ups for ORD-100 (3/3)

// ✅ Complete! Best: usps @ $8.99

That’s it—a Map, a completion check, and cleanup. The pattern: collect by correlation key, check for completeness, emit and remove when done.

Aggregator Completion Strategies

How do you know when the aggregation is complete? Several strategies exist:

| Strategy | When to Use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Count-based | Fixed number of parts | “Aggregate when we have all 3 shipping quotes” |

| Timeout-based | Best-effort collection | “Aggregate after 5 seconds with whatever we have” |

| Marker-based | One message signals completion | “Aggregate when we receive the ‘END’ message” |

| Content-based | Message content indicates completeness | “Aggregate when total items equals order item count” |

The Typescript example above uses count-based completion—we know we’re done when we have quotes from all three carriers. For timeout-based aggregation, you’d add a timer that fires after N seconds, completing with whatever messages have arrived.

Putting It All Together: Travel Itinerary Pricing

These patterns often combine into larger compositions. The classic example is Scatter-Gather: broadcast a request to multiple recipients, then aggregate their responses.

Consider how travel booking sites work. When you search for a trip, they need to find flights, hotels, and rental cars from multiple providers, then combine everything into complete packages with total pricing. Here’s the flow:

TripRequest: "NYC → LA, Dec 26-30, 2 adults"

│

▼

[SPLITTER]

(one query per component)

│

┌───────────────┼───────────────┐

▼ ▼ ▼

Flight Hotel Car Rental

Query Query Query

│ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼

[ROUTER] [ROUTER] [ROUTER]

│ │ │

├─→ United ├─→ Marriott ├─→ Hertz

├─→ Delta ├─→ Hilton ├─→ Enterprise

└─→ JetBlue └─→ Airbnb └─→ Turo

│ │ │

└───────────────┴───────────────┘

│

▼

[FILTER]

(drop sold out, over budget)

│

▼

[AGGREGATOR]

(combine into complete packages)

│

▼

ItineraryPackages: [

{ flight: "Delta", hotel: "Marriott", car: "Hertz", total: $1,247 },

{ flight: "United", hotel: "Airbnb", car: "Turo", total: $892 },

...

]

All four patterns we covered today show up:

Splitter decomposes the trip request into component queries (flight, hotel, car). Each carries the original

tripIdas a correlation identifier.Content-Based Router fans out each component to its providers. Flight queries go to United, Delta, and JetBlue. Hotel queries go to Marriott, Hilton, and Airbnb. That’s 9 parallel API calls from a single search.

Message Filter drops options that won’t work: sold out rooms, flights that exceed the budget, cars unavailable for those dates.

Aggregator collects quotes by

tripId, waits until it has at least one option for each component, then builds all possible combinations sorted by total price.

The result? “Budget option: $892 (United + Airbnb + Turo)” and “Comfort option: $1,247 (Delta + Marriott + Hertz)”.

This is exactly how services like Kayak, Google Flights, and Hopper work. They scatter requests to providers, filter the noise, and aggregate the best options for you. The patterns handle the complexity: parallelism, resilience (if one provider times out, you still have others), and flexibility (adding a new provider means subscribing to an existing queue).

Summary

Today we explored four Message Routing patterns that control how messages flow through your system:

| Pattern | Does | Statefulness |

|---|---|---|

| Content-Based Router | Directs messages to different destinations | Stateless |

| Message Filter | Drops non-matching messages | Stateless |

| Splitter | Breaks one message into many | Stateless |

| Aggregator | Combines many messages into one | Stateful |

The Key Insight

These patterns are just functions over message streams:

- Router:

Message → Channel(selection) - Filter:

Message → Maybe Message(predicate) - Splitter:

Message → List[Message](flatMap) - Aggregator:

List[Message] → Message(reduce)

If you know map, filter, flatMap, and reduce from functional programming, you already understand these patterns. The difference is that in messaging systems, these operations happen across time and space—messages arrive asynchronously from distributed sources, and your patterns must handle this gracefully.

Build It Yourself Recap

We implemented each pattern in a different language to show these concepts are universal:

| Pattern | Language | Core Idea |

|---|---|---|

| Content-Based Router | Python | Predicate matching with regex content inspection |

| Message Filter | TypeScript | Composable predicates with allOf/anyOf combinators |

| Splitter | Gleam | list.index_map with correlation metadata |

| Aggregator | TypeScript | Map-based collection with completion check |

Each implementation is under 50 lines. Production message brokers add durability, distribution, and monitoring, but the core logic is identical.

What’s Next

We’ve been throwing around the word “message” pretty loosely. Tomorrow we’ll get more precise and explore the different kinds of messages: Document Messages that carry data, Command Messages that request action, and Event Messages that announce what happened. We’ll also touch on CQRS and how separating reads from writes changes how you think about message flow.

See you on Day 5! 🎄

This post is part of the Advent of Enterprise Integration Patterns series. Check out the introduction or follow along with the enterprise-integration-patterns tag. All patterns referenced are from the classic book Enterprise Integration Patterns by Gregor Hohpe and Bobby Woolf.