Welcome back to the Advent of Enterprise Integration Patterns! In Day 2, we introduced Message Endpoints and the Messaging Gateway pattern to decouple our application from the transport layer, plus Pipes and Filters for composable event processing. We ended with a bit of a cliffhanger: running producers and consumers as separate processes worked great for distribution, but left us with fragmented data across isolated ETS stores.

Today we’re going to tackle that problem head-on—and then explore the different types of message channels available to us.

Quick Recap: Shared Database

The data fragmentation problem we identified at the end of Day 2 had a straightforward solution: shared storage. Instead of each consumer maintaining its own ETS table, all consumers write to a shared PostgreSQL database. The producer’s HTTP API can then query that same database to serve read requests.

We implemented this with a pluggable EventStore abstraction:

/// Event store - a record of functions that any backend must implement

pub type EventStore {

EventStore(

insert: fn(AuditEvent) -> Bool,

list_all: fn() -> List(AuditEvent),

get: fn(String) -> Result(AuditEvent, Nil),

)

}

// Create an ETS-backed store (in-memory, per-process)

pub fn create_ets() -> EventStore

// Create a PostgreSQL-backed store (shared across processes)

pub fn create_postgres(config: PostgresConfig) -> EventStore

Following 12-factor app principles, the storage backend is configured via environment variables:

# In-memory ETS (default for local development)

CHRONICLE_STORE=ets just run

# PostgreSQL (for distributed deployments)

CHRONICLE_STORE=postgres just run

The beauty of this abstraction is that consumers and the router don’t change at all—they just call event_store.insert() and event_store.list_all(). Whether those operations hit an in-memory ETS table or a PostgreSQL connection pool is purely a configuration concern.

This is a well-established pattern: consumers write to a shared database, the API reads from it. We won’t dwell on it further since it’s table stakes for any real distributed system. If you want to see the implementation details, check out the day-3-eip tag.

Now, onto the main event: Message Channels.

Message Channels: The Pipes in Your System

So far, we’ve been using a single channel for all our events. Every audit event—whether it’s a user login, a document export, or a permission change—flows through the same pipe. That works fine for simple use cases, but real systems need more sophisticated routing.

The Enterprise Integration Patterns book describes several types of channels, each optimized for different communication styles. Today we’ll explore four of them:

- Point-to-Point Channel — One sender, one receiver (already implemented!)

- Publish-Subscribe Channel — One sender, multiple independent receivers

- Datatype Channel — Channels organized by message type

- Invalid Message Channel — Handling malformed or unexpected messages

Let’s dive into each one.

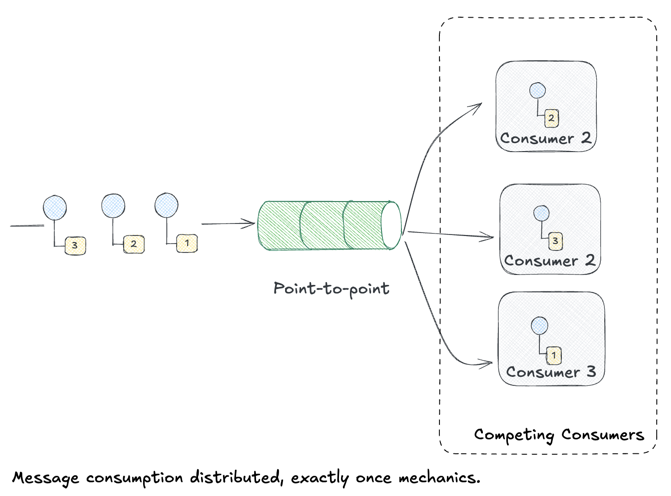

Point-to-Point Channel (Recap)

We implemented Point-to-Point Channels back in Day 1, so this is just a quick refresher.

“The sender puts the message on the channel, and the receiver retrieves the message from the channel. The channel ensures that each message is received by only one receiver.”

Key characteristics:

- One-to-one delivery: Each message is consumed by exactly one receiver

- Load balancing: When combined with Competing Consumers, work is distributed across multiple receivers

- FIFO ordering (usually): Messages are typically processed in order, though competing consumers can introduce out-of-order delivery

In Chronicle, our OTP channel and RabbitMQ queue both implement point-to-point semantics. When you send an event, exactly one consumer processes it. Perfect for work distribution—but what if you need multiple systems to all see every event?

Chronicle Implementation

Gleam’s actor model with OTP makes point-to-point natural. Our channel module uses a Subject (typed mailbox) that consumers poll:

/// The channel is simply an actor holding a queue

pub opaque type ChannelState {

ChannelState(events: queue.Queue(AuditEvent))

}

/// Send puts an event on the queue

pub fn send(channel: Subject(ChannelMessage), event: AuditEvent) -> Nil {

actor.send(channel, Enqueue(event))

}

/// Receive atomically pops from the queue - only one consumer gets it

pub fn receive(channel: Subject(ChannelMessage), timeout: Int) -> Result(AuditEvent, Nil) {

actor.call(channel, Dequeue(_), timeout)

}

The key is that Dequeue is an atomic operation—when multiple consumers call it concurrently, each message goes to exactly one.

Build It Yourself: Python

Without any messaging infrastructure, you can implement point-to-point with a simple thread-safe queue:

from queue import Queue

from threading import Thread

# The "channel" is just a queue

channel = Queue()

def producer():

for i in range(10):

channel.put({"id": i, "action": "test"})

def consumer(name):

while True:

event = channel.get() # Blocks until message available

print(f"{name} processing event {event['id']}")

channel.task_done()

# Multiple consumers compete for messages

Thread(target=producer).start()

Thread(target=consumer, args=("worker-1",)).start()

Thread(target=consumer, args=("worker-2",)).start()

That’s it! Python’s Queue handles the “exactly one receiver” guarantee. The pattern is the same whether you use a local queue, Redis, or RabbitMQ—only the transport changes.

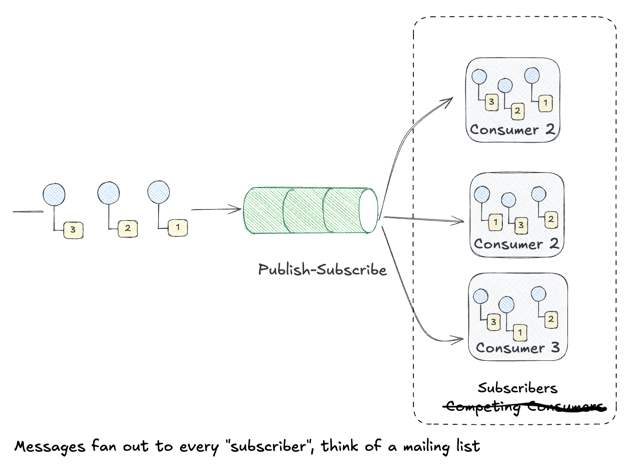

Publish-Subscribe Channel

The Publish-Subscribe Channel flips the model:

“A Publish-Subscribe Channel broadcasts an event to all subscribers. Each subscriber receives its own copy of the message.”

Where Point-to-Point is about work distribution (divide tasks among workers), Publish-Subscribe is about event notification (inform everyone who cares).

Key characteristics:

- One-to-many delivery: Every subscriber receives every message

- Decoupled subscribers: Publishers don’t know (or care) who’s listening

- Independent processing: Each subscriber handles messages at their own pace

Real-world examples:

- Audit logging: Security, compliance, and analytics systems all need to see every event

- Cache invalidation: Multiple services need to know when shared data changes

- Event sourcing: Different read models subscribe to the same event stream

In Chronicle, imagine these subscribers all interested in audit events:

- Search indexer — Updates Elasticsearch for full-text search

- Analytics pipeline — Aggregates metrics in a data warehouse

- Real-time dashboard — Pushes to WebSockets for live monitoring

- Compliance archive — Writes to immutable cold storage

With Point-to-Point, only one of these would receive each event. With Publish-Subscribe, they all do—independently, reliably, at their own pace.

Chronicle Implementation

For pub-sub in Chronicle, we use RabbitMQ’s fanout exchange. When you bind multiple queues to a fanout exchange, every message goes to all of them:

// The topology module binds multiple queues to the same exchange

pub fn setup_pubsub(ch: Channel) -> Result(Nil, String) {

// One fanout exchange

let ex = exchange.new("audit_broadcast")

|> exchange.with_type(exchange.Fanout)

// Multiple subscriber queues - each gets a copy

use _ <- result.try(queue.bind(ch, "search_indexer", "audit_broadcast", ""))

use _ <- result.try(queue.bind(ch, "analytics", "audit_broadcast", ""))

use _ <- result.try(queue.bind(ch, "dashboard", "audit_broadcast", ""))

Ok(Nil)

}

The fanout exchange ignores routing keys entirely—every bound queue receives every message.

Build It Yourself: TypeScript

Without a message broker, pub-sub is just a list of callbacks:

type Event = { id: string; action: string };

type Subscriber = (event: Event) => void;

// The "channel" maintains a subscriber list

const subscribers: Subscriber[] = [];

function subscribe(handler: Subscriber) {

subscribers.push(handler);

return () => { // Return unsubscribe function

const idx = subscribers.indexOf(handler);

if (idx > -1) subscribers.splice(idx, 1);

};

}

function publish(event: Event) {

// Fan out to ALL subscribers

subscribers.forEach(sub => sub(event));

}

// Multiple independent subscribers

subscribe(e => console.log(`[Search] Indexing ${e.id}`));

subscribe(e => console.log(`[Analytics] Recording ${e.id}`));

subscribe(e => console.log(`[Dashboard] Displaying ${e.id}`));

publish({ id: "evt-1", action: "user.login" });

// Output:

// [Search] Indexing evt-1

// [Analytics] Recording evt-1

// [Dashboard] Displaying evt-1

The EventEmitter pattern in Node.js, React’s context, Redux’s store.subscribe()—they’re all variations of this. The broker (RabbitMQ, Kafka, etc.) adds durability and distribution, but the core pattern is just “call all the callbacks.”

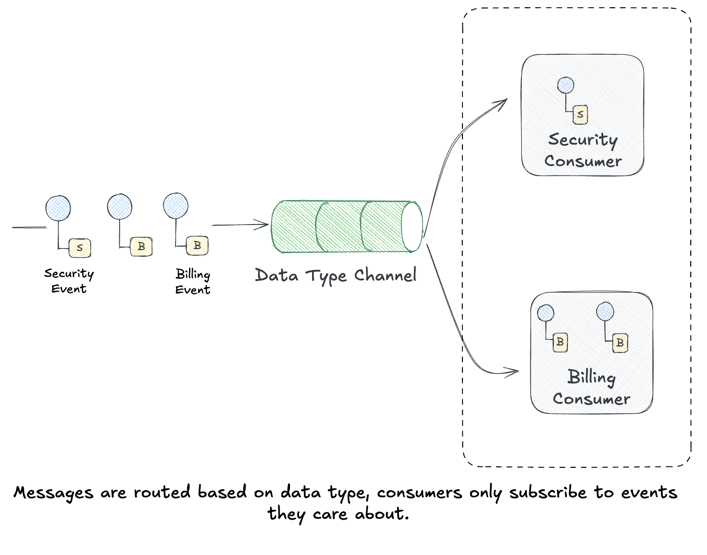

Datatype Channel

The Datatype Channel pattern organizes channels by message type:

“Use a separate Datatype Channel for each data type, so that all data on a particular channel is of the same type.”

Instead of one big channel carrying heterogeneous messages, you create specialized channels for each message type. Think of it like having separate inboxes for bills, personal mail, and packages.

Key characteristics:

- Type safety: Consumers know exactly what schema to expect

- Independent scaling: High-volume message types get dedicated resources

- Simpler consumers: No need to filter or switch on message type

Real-world examples:

user-eventschannel for signups, logins, profile updatesorder-eventschannel for purchases, refunds, fulfillmentsecurity-eventschannel for auth failures, permission changes, suspicious activity

In Chronicle, we might split our monolithic audit channel into:

chronicle.events.security → Security team's SIEM

chronicle.events.billing → Finance systems

chronicle.events.user → Product analytics

Each consumer subscribes only to the events they care about. The security team doesn’t wade through billing events; the analytics pipeline ignores security alerts. Separation of concerns at the messaging layer.

This pattern often works hand-in-hand with a Content-Based Router that inspects incoming messages and routes them to the appropriate datatype channel. We’ll explore routing patterns in more depth soon.

Chronicle Implementation

Our routing key derives from the event type. When publishing, Gleam pattern matches to determine the key:

/// Get the routing key for this event

pub fn routing_key(event: AuditEvent) -> String {

case event.event_type {

Some(et) -> et // Explicit: "security.login"

None -> derive_event_type(event.resource_type, event.action)

}

}

/// The gateway uses this when publishing

pub fn publish(conn: Connection, evt: AuditEvent) -> Result(Nil, String) {

publisher.publish(

exchange: "audit_events",

routing_key: event.routing_key(evt), // "security.login"

payload: event_to_json(evt),

)

}

RabbitMQ’s topic exchange then matches security.login against bindings like security.# (security queue) and # (catch-all queue). The routing is declarative in config, not hardcoded.

Build It Yourself: Go

Without a message broker, datatype channels are just a map of type → handlers:

package main

type Event struct {

Type string // "security.login", "user.created", etc.

Data map[string]any

}

type Handler func(Event)

// Route events by type prefix

type Router struct {

handlers map[string][]Handler

}

func (r *Router) Register(pattern string, h Handler) {

r.handlers[pattern] = append(r.handlers[pattern], h)

}

func (r *Router) Route(event Event) {

// Check for exact match, then prefix match

for pattern, handlers := range r.handlers {

if matches(event.Type, pattern) {

for _, h := range handlers {

h(event)

}

}

}

}

// Simple wildcard: "security.*" matches "security.login"

func matches(eventType, pattern string) bool {

if pattern == "#" { return true }

prefix := strings.TrimSuffix(pattern, ".*")

return strings.HasPrefix(eventType, prefix)

}

func main() {

r := &Router{handlers: make(map[string][]Handler)}

// Type-specific handlers

r.Register("security.*", func(e Event) {

fmt.Printf("[SECURITY] %s\n", e.Type)

})

r.Register("user.*", func(e Event) {

fmt.Printf("[USER] %s\n", e.Type)

})

r.Register("#", func(e Event) { // Catch-all for analytics

fmt.Printf("[ANALYTICS] %s\n", e.Type)

})

r.Route(Event{Type: "security.login"})

// Output:

// [SECURITY] security.login

// [ANALYTICS] security.login

}

The pattern is just a switch/match on type with wildcard support. RabbitMQ’s topic exchange is exactly this, but distributed and durable.

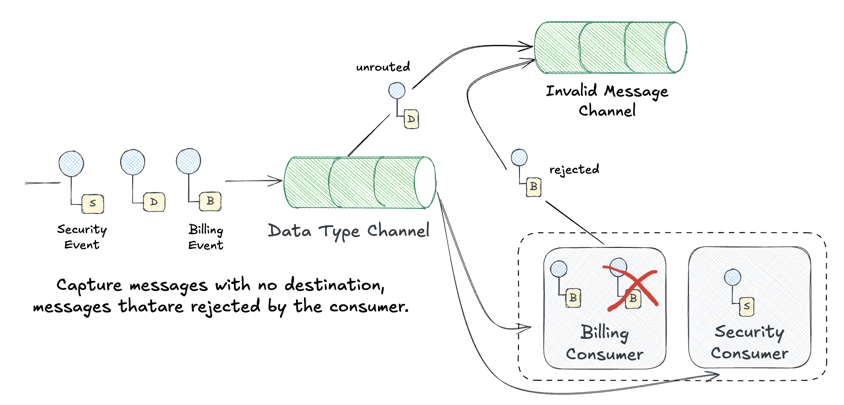

Invalid Message Channel

What happens when a message arrives that can’t be processed? Maybe it’s malformed JSON. Maybe it references a schema version the consumer doesn’t understand. Maybe it’s addressed to a queue that doesn’t exist.

The Invalid Message Channel (also known as a Dead Letter Queue or DLQ) gives these problematic messages a place to go:

“The receiver should move the improper message to an Invalid Message Channel, a special channel for messages that could not be processed by their receivers.”

Key characteristics:

- No data loss: Bad messages are captured, not silently dropped

- Debugging aid: Operators can inspect failed messages and diagnose issues

- Retry capability: Some DLQ systems support replaying messages after fixes

- Alerting hook: Sudden spikes in invalid messages indicate problems

What ends up in the DLQ?

- Malformed messages: Invalid JSON, missing required fields, wrong data types

- Poison messages: Messages that consistently cause consumer crashes

- Expired messages: Messages that exceeded their TTL (time-to-live)

- Unroutable messages: Messages sent to non-existent queues or exchanges

Real-world flow:

Producer → Main Queue → Consumer

↓ (on failure)

Dead Letter Queue → Monitoring/Alerting

↓

Manual Review

↓

Fix & Replay

In Chronicle, an Invalid Message Channel would catch events that fail validation after they’ve already been queued—perhaps due to schema evolution mismatches between producer and consumer versions. Instead of crashing the consumer or losing the event, we’d route it to chronicle.events.dead-letter for investigation.

RabbitMQ has built-in DLQ support through Dead Letter Exchanges. When a message is rejected, expires, or exceeds the queue length, RabbitMQ automatically routes it to a configured dead letter exchange. We’ll wire this up to make Chronicle more resilient to bad data.

Chronicle Implementation

Gleam’s Result type naturally surfaces errors. Our consumer wraps message processing and routes failures:

/// Consumer callback with error handling

fn handle_message(payload: String, channel: Channel, tag: Int) {

case json_to_event(payload) {

Ok(event) -> {

// Process successfully - acknowledge

process_event(event)

queue.ack(channel, tag)

}

Error(_) -> {

// Parse failed - send to DLQ

log.error("Failed to parse: " <> payload)

queue.nack(channel, tag, requeue: False) // Goes to DLX

}

}

}

The requeue: False tells RabbitMQ “don’t put this back on the main queue”—if a DLX is configured, the message goes there instead.

Build It Yourself: TypeScript

Without infrastructure, a DLQ is just a secondary collection for failed items:

type Event = { id: string; data: string };

type DeadLetter = { event: Event; error: string; attempts: number };

// Two queues: main processing and dead letters

const mainQueue: Event[] = [];

const deadLetterQueue: DeadLetter[] = [];

function enqueue(event: Event) {

mainQueue.push(event);

}

function process(handler: (e: Event) => void) {

while (mainQueue.length > 0) {

const event = mainQueue.shift()!;

try {

handler(event);

console.log(`✓ Processed ${event.id}`);

} catch (err) {

// Route to dead letter queue instead of losing the message

deadLetterQueue.push({

event,

error: String(err),

attempts: 1,

});

console.log(`💀 Moved ${event.id} to DLQ`);

}

}

}

// Validation that might fail

function handleEvent(event: Event) {

if (!event.data) {

throw new Error("Empty data not allowed");

}

// Process valid event...

}

// Send mix of good and bad events

enqueue({ id: "1", data: "valid" });

enqueue({ id: "2", data: "" }); // Will fail validation

enqueue({ id: "3", data: "also valid" });

process(handleEvent);

// Later: inspect or replay dead letters

console.log(`\nDLQ contains ${deadLetterQueue.length} failed messages:`);

deadLetterQueue.forEach(dl => {

console.log(` ${dl.event.id}: ${dl.error}`);

});

The pattern is: try to process, catch failures, route to a separate channel. Whether that’s an in-memory array, a database table, or a RabbitMQ DLX—the semantics are identical.

Implementation: Datatype Channels with Topic Exchanges

Let’s implement Datatype Channels in Chronicle using RabbitMQ’s topic exchanges. The key insight is that we can use routing keys to direct messages to type-specific queues.

Event Types as Routing Keys

First, we add an event_type field to our audit events:

pub type AuditEvent {

AuditEvent(

id: String,

actor: String,

action: String,

resource_type: String,

resource_id: String,

timestamp: String,

// NEW: Datatype Channel routing key

event_type: Option(String),

// ... enrichment fields ...

)

}

/// Derive event_type from resource_type and action

/// e.g., ("User", "Login") -> "user.login"

fn derive_event_type(resource_type: String, action: String) -> String {

string.lowercase(resource_type) <> "." <> string.lowercase(action)

}

The event_type follows a hierarchical format like security.login, user.created, or billing.charge. This maps directly to RabbitMQ’s routing key syntax for topic exchanges.

Configuration-Driven Topology

Rather than hardcoding queue names, we define our topology in a configuration file (priv/chronicle.toml):

[exchanges.audit_events]

type = "topic"

durable = true

[[routes]]

name = "security_events"

exchange = "audit_events"

queue = "chronicle.security"

routing_key = "security.#"

dead_letter_exchange = "dead_letter"

dead_letter_queue = "chronicle.security.dlq"

[[routes]]

name = "user_events"

exchange = "audit_events"

queue = "chronicle.users"

routing_key = "user.#"

[[routes]]

name = "all_events"

exchange = "audit_events"

queue = "chronicle.all"

routing_key = "#" # Catch-all for analytics

The # wildcard matches zero or more words—so security.# matches security.login, security.logout, and security.auth_failure.

Automatic Topology Setup

A new topology module ensures all exchanges, queues, and bindings exist before consumers start:

/// Ensure all configured topology exists in RabbitMQ

pub fn ensure_topology(ch: Channel, config: RoutingConfig) -> Result(Nil, String) {

// 1. Declare all exchanges

use _ <- result.try(declare_exchanges(ch, config))

// 2. Declare all queues (including DLQs)

use _ <- result.try(declare_queues(ch, config))

// 3. Create bindings (routing key → queue)

use _ <- result.try(create_bindings(ch, config))

Ok(Nil)

}

This is idempotent—safe to call multiple times, which is important for rolling deployments.

Publishing with Routing Keys

The rabbit module now publishes to the topic exchange with the event’s routing key:

pub fn publish(conn: RabbitConnection, evt: AuditEvent) -> Result(Nil, String) {

let payload = event_to_json(evt)

// Use topic exchange with event_type as routing key

let #(exchange, routing_key) = case conn.exchange {

Some(ex) -> #(ex, event.routing_key(evt))

None -> #("", conn.queue_name) // Fallback to direct queue

}

publisher.publish(

channel: conn.channel,

exchange: exchange,

routing_key: routing_key,

payload: payload,

options: [publisher.Persistent(True), ...],

)

}

When a producer sends a security.login event, it automatically routes to:

chronicle.security(matchessecurity.#)chronicle.all(matches#)

But not to chronicle.users (which expects user.#).

Consumer Roles

Consumers can now subscribe to specific routes via configuration:

[[consumers]]

name = "security"

description = "Security team - handles auth events"

routes = ["security_events"]

instances = 2

[[consumers]]

name = "analytics"

description = "Analytics pipeline - receives all events"

routes = ["all_events"]

instances = 1

Starting a consumer with a specific role:

# Composable variables for consumer roles

just role=security transport=rabbitmq consumer # Only security events

just role=analytics transport=rabbitmq consumer # All events (catch-all)

just role=billing transport=rabbitmq consumers 3 # 3 billing consumers

Implementation: Invalid Message Channel (DLQ)

RabbitMQ’s dead letter exchange (DLX) feature handles most of the heavy lifting. We configure it at the queue level:

/// Declare a queue with dead letter exchange settings

fn declare_queue_with_dlx(ch: Channel, route: RouteConfig) -> Result(Nil, String) {

case route.dead_letter_exchange {

Some(dlx) -> declare_queue_with_args(ch, route.queue, dlx)

None -> declare_simple_queue(ch, route.queue)

}

}

When a message is rejected (nack without requeue) or expires, RabbitMQ automatically routes it to the configured DLX.

Manual Rejection

For messages we can parse but can’t process, we provide an explicit rejection:

/// Reject a message - routes to DLQ if configured

pub fn nack_to_dlq(ch: Channel, delivery_tag: Int) -> Result(Nil, String) {

reject(ch, delivery_tag, False) // requeue = False → goes to DLQ

}

DLQ Monitoring

The invalid_message module provides utilities for inspecting and replaying dead-lettered messages:

/// Get stats for all configured DLQs

pub fn get_dlq_stats(ch: Channel, config: RoutingConfig) -> List(#(String, Int))

/// Replay all messages from a DLQ back to their original exchanges

pub fn replay_all(ch: Channel, dlq_name: String) -> Result(Int, String)

With just commands:

just list-queues # See message counts in all queues

just event=security send # Test routing to security queue

just event=billing send # Test routing to billing queue

just event=user send # Test routing to user queue

Summary

We’ve now surveyed and implemented multiple message channel types:

| Channel Type | Delivery | Implementation | DIY Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point-to-Point | One receiver | RabbitMQ queues | Thread-safe queue |

| Publish-Subscribe | All receivers | Fanout exchange | List of callbacks |

| Datatype | Type-specific | Topic exchange | Map of type → handlers |

| Invalid Message | Error handling | Dead letter exchange | Secondary error channel |

The Takeaway

Notice how simple the “build it yourself” examples are? These patterns aren’t magic—they’re fundamental data structures:

- Point-to-Point: A queue with atomic pop

- Pub-Sub: A list you iterate

- Datatype: A map you look up

- DLQ: A second queue for errors

What message brokers like RabbitMQ add is distribution, durability, and decoupling. The patterns themselves are language-agnostic and can be implemented in 20 lines of code. Understanding the core pattern helps you choose the right tool and debug issues when they arise.

Same Patterns, Different Stacks

While we built pure examples to illustrate the concepts, in practice your messaging system handles these patterns for you. Here’s how the major platforms implement them:

RabbitMQ (what Chronicle uses):

- Point-to-Point: Default queue behavior—multiple consumers round-robin

- Pub-Sub: Fanout exchanges broadcast to all bound queues

- Datatype: Topic exchanges with routing key wildcards (

security.#) - DLQ: Dead Letter Exchanges (DLX) with automatic routing on rejection/expiry

- Point-to-Point: Consumer groups—each partition consumed by one group member

- Pub-Sub: Multiple consumer groups on the same topic, each gets all messages

- Datatype: Separate topics per type, or single topic with Kafka Streams filtering

- DLQ: Kafka Connect’s

errors.deadletterqueue.topic.nameor manual error topics

Amazon SQS/SNS:

- Point-to-Point: Standard SQS queues with competing consumers

- Pub-Sub: SNS topics fan out to multiple SQS queue subscriptions

- Datatype: SNS message filtering with subscription filter policies

- DLQ: Native SQS dead-letter queues with

maxReceiveCountredrive policy

Mix and Match: Kafka Connect as a Bridge

The real power emerges when you combine systems. Kafka Connect lets you bridge Kafka’s durable log with purpose-built messaging services:

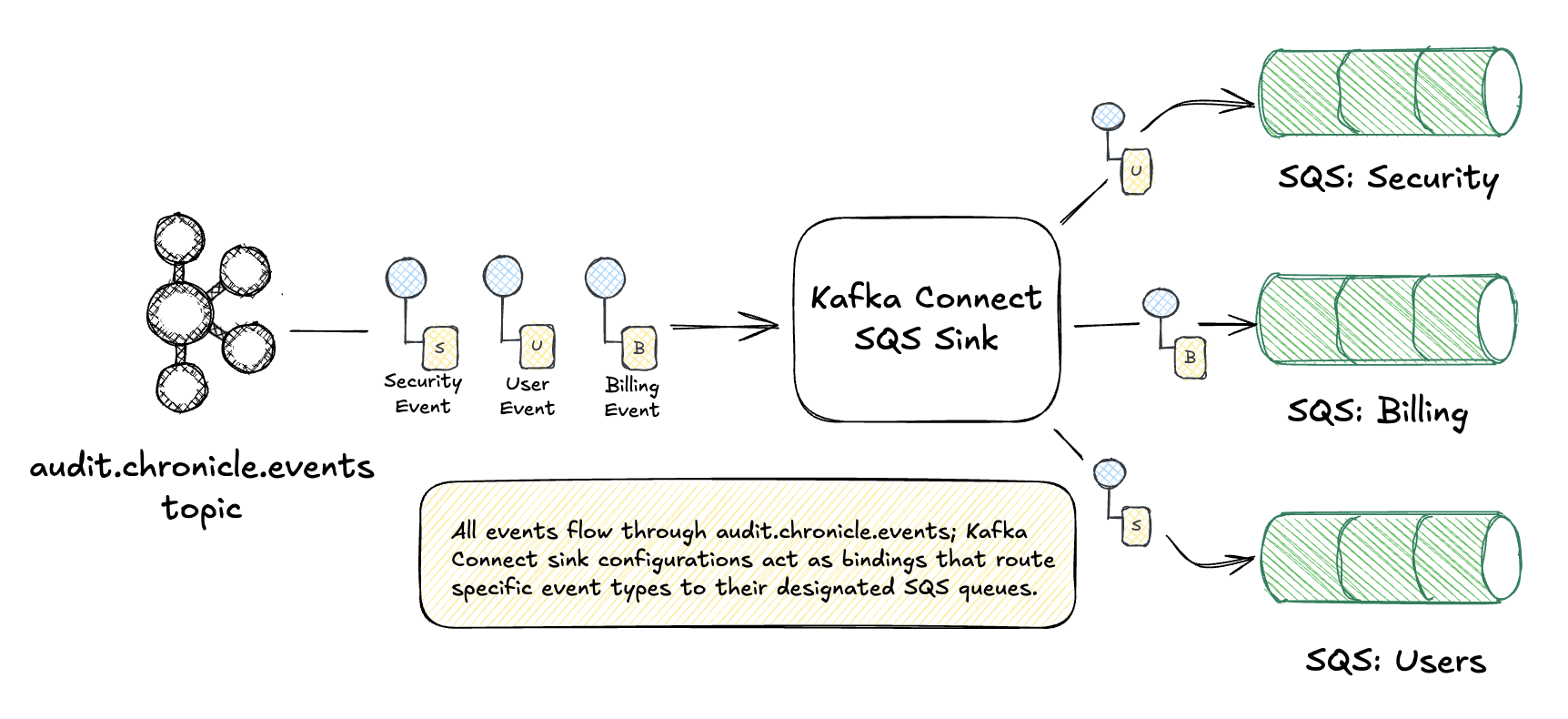

Kafka → SQS (Point-to-Point / Datatype):

Use Kafka Connect’s Single Message Transforms (SMT) to route messages to different SQS queues based on message content—datatype routing very similar to RabbitMQ’s topic exchanges. You can think of Kafka Connect sink connectors as analogous to RabbitMQ’s exchange-to-queue bindings: they define where messages flow based on configuration.

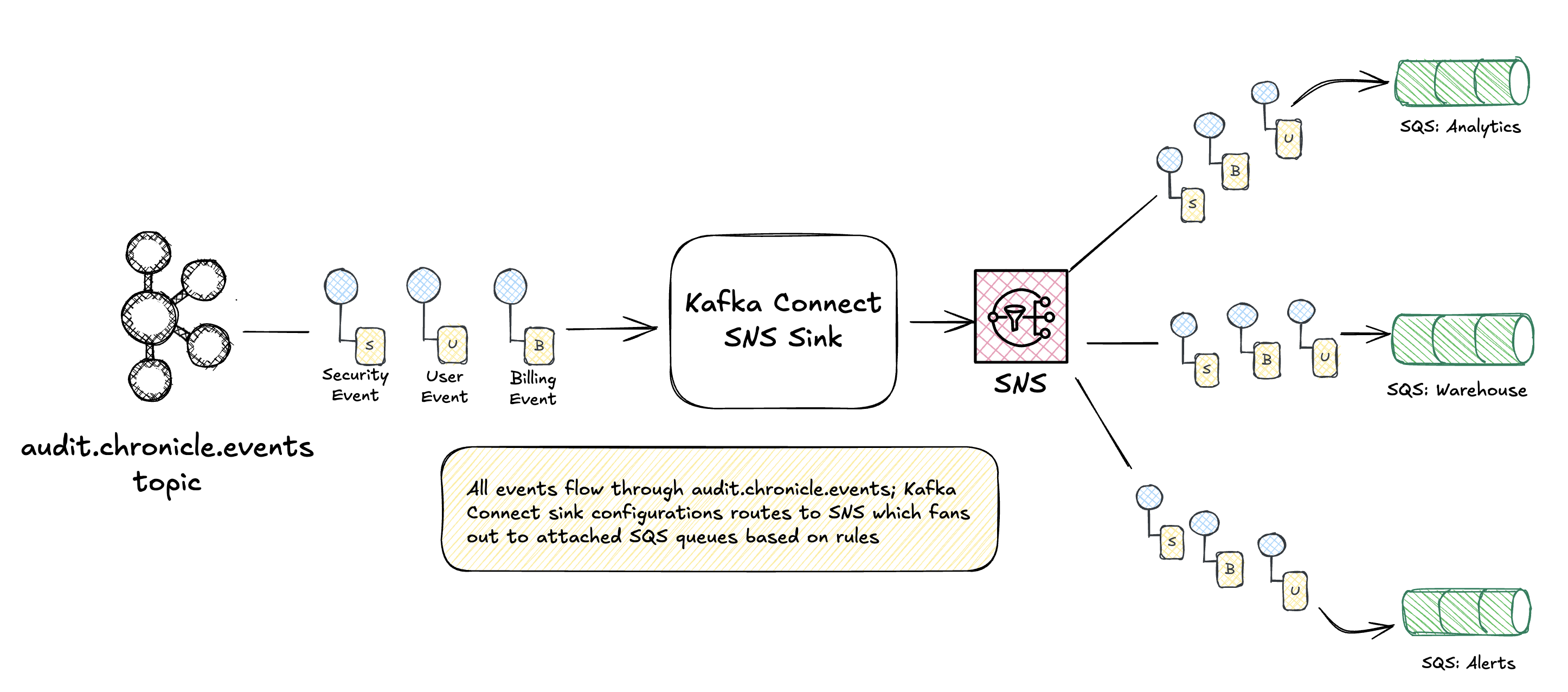

Kafka → SNS → SQS (Pub-Sub Fan-out):

Kafka provides durable storage and replay; SNS handles fan-out to multiple downstream teams. Each SQS queue can have its own consumers, DLQ, and processing guarantees. For managed Kafka on AWS, kafka-connect-amazon-sns simplifies routing events to an SNS topic, broadcasting to attached SQS queues.

Kafka provides durable storage and replay; SNS handles fan-out to multiple downstream teams. Each SQS queue can have its own consumers, DLQ, and processing guarantees. For managed Kafka on AWS, kafka-connect-amazon-sns simplifies routing events to an SNS topic, broadcasting to attached SQS queues.

Why mix systems?

- Kafka excels at durable, replayable event logs

- SQS provides simple point-to-point with built-in DLQ and visibility timeout

- SNS enables fan-out without Kafka consumer group complexity

- Each team consumes from their preferred interface

The patterns don’t care about the wire protocol. A security.login event might flow through Kafka, get transformed by Kafka Connect, land in SNS, and fan out to three SQS queues—but it’s still just pub-sub with datatype routing.

Key enablers for our RabbitMQ implementation:

- Event types as routing keys —

security.login,user.created, etc. - Configuration-driven topology —

chronicle.tomldefines the routing mesh - Automatic DLQ setup — Every route can have its own dead letter queue

- Consumer roles — Start consumers for specific message types

This gives us fine-grained control over message flow while keeping the application code clean. Producers just send events; the routing layer handles distribution.

What’s Next

Whew! This one was a bit long winded! I was worried this was getting a bit out of control but I think this does a decent job covering the fundamental channel types and demonstrates how you can implement these yourself as well as how they are implemented in populate messaging solutions. In the next post, we’ll explore Message Routing patterns:

- Content-Based Router — Route by message content

- Message Filter — Selective consumption

- Splitter — One message becomes many

- Aggregator — Many messages become one

These build on today’s channel foundation to enable sophisticated event processing pipelines.

Stay tuned! 🎄

This post is part of the Advent of Enterprise Integration Patterns series. Check out the introduction or follow along with the enterprise-integration-patterns tag.

Code for this series is available at github.com/jamescarr/chronicle. Today’s changes: day-3-eip.