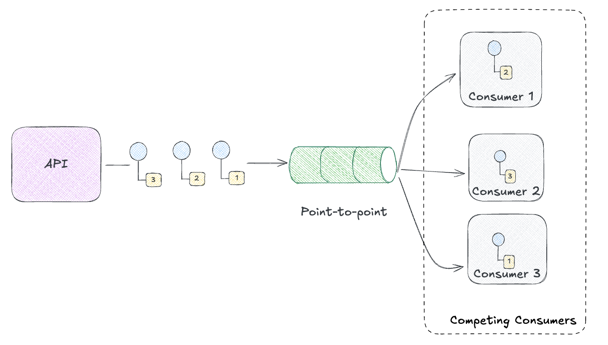

Welcome back to the Advent of Enterprise Integration Patterns! Yesterday we got our hands dirty with Point-to-Point Channels and Competing Consumers, building the bones of Chronicle using OTP actors. We can send audit events and have them processed reliably by multiple consumers racing to grab work. Pretty cool!

But here’s the thing: that implementation is tightly coupled to OTP. What happens when we want to deploy Chronicle across multiple machines? Or swap in RabbitMQ for a proper message broker? Right now, that would mean rewriting half our codebase.

Today we’re going to fix that. We’ll introduce two patterns that transform Chronicle from a single-process demo into something that could actually scale: Message Endpoints for cleanly separating producers from consumers, and Pipes and Filters for composable event processing.

Let’s dive in.

Quick Recap: Where We Left Off

Yesterday’s Chronicle had a simple architecture utilizing the following patterns.

- Point-to-Point Channel: Messages queue up and are delivered to exactly one receiver

- Competing Consumers: Multiple receivers race to process messages

Events came in through HTTP, the router pushed them onto an OTP channel, and consumers pulled them off and stored them in ETS. It worked great… as long as everything ran in one BEAM instance.

The problem? Our router directly called channel.send(). Our consumers directly called channel.receive(). The transport mechanism (OTP actors) was baked into every layer. Classic tight coupling.

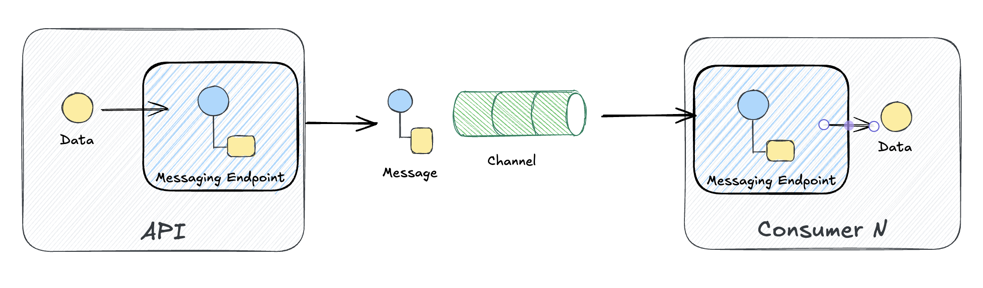

Message Endpoints: Connecting to the Channel

The Message Endpoint pattern describes how an application connects to a messaging channel. EIP distinguishes between:

- Sending Endpoints (producers): Push messages onto channels

- Receiving Endpoints (consumers): Pull messages from channels

Message Endpoint: How applications connect to channels as senders or receivers

Message Endpoint: How applications connect to channels as senders or receivers

Why does this matter? In real-world systems, these roles are often more fluid than the simple “producer vs consumer” dichotomy suggests. A single service frequently acts as both:

- An order service consumes “payment completed” events, processes them, then produces “order fulfilled” events

- A notification service consumes various domain events, then produces “notification sent” events for audit trails

- Even our Chronicle API is both: it’s a consumer of HTTP requests and a producer of messages to the channel

The endpoint pattern gives you the vocabulary and abstraction to handle this cleanly. Your service configures which endpoints it needs — maybe just producing, maybe just consuming, maybe both. But the important thing to keep in mind is that an when you have both, you basically will have two endpoints: one for consuming and one for producing. The abstraction basically is a clear distinction of how messages flow in and out of your system. An inbox and an outbox so to speak.

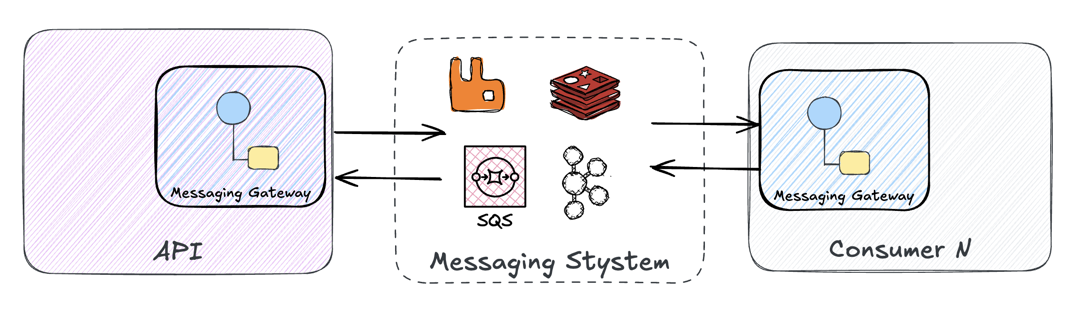

The Messaging Gateway

But here’s the thing: we don’t want our endpoint code caring about how messages travel. Whether events flow through OTP actors or RabbitMQ queues shouldn’t change our application logic.

This is where the Messaging Gateway pattern comes in:

“A Messaging Gateway is a class that wraps messaging-specific method calls and exposes domain-specific methods to the application.”

In plain English: hide the messaging plumbing behind a clean interface. Your endpoints call the gateway; the gateway handles the transport details. For example in my old Java days, I liked to leverage the Spring Integration framework which included the interfaces MessageChannel for sending and SubscribableChannel for consuming, with specific dependecies like spring-amqp defining the actual details under the hood.

Messaging Gateway: Applications talk to a gateway that hides the messaging system

Messaging Gateway: Applications talk to a gateway that hides the messaging system

Chronicle implements this with an opaque Gateway type:

/// The Gateway handle - opaque to callers

pub opaque type Gateway {

OtpGateway(channel: Subject(channel.ChannelMessage))

RabbitGateway(connection: rabbit.RabbitConnection)

}

/// Send an event through the gateway (fire-and-forget)

pub fn send_event(gateway: Gateway, event: AuditEvent) -> Nil {

case gateway {

OtpGateway(channel:) -> channel.send(channel, event)

RabbitGateway(connection:) -> {

case rabbit.publish(connection, event) {

Ok(_) -> Nil

Error(msg) -> {

log.error("Failed to publish to RabbitMQ: " <> msg)

Nil

}

}

}

}

}

Notice that Gateway is an opaque type. Callers can’t peek inside to see whether it’s OTP or RabbitMQ. They just call gateway.send_event() and trust it’ll work. The router doesn’t care about transport anymore:

// Works identically for OTP or RabbitMQ

gateway.send_event(ctx.gateway, audit_event)

Following 12-factor app principles, we configure the transport via environment variables. No code changes needed to switch — just flip an environment variable and restart.

Endpoint Modes

In a distributed system, you often want to run producers and consumers as separate processes for scaling or deployment flexibility.

Chronicle supports three modes:

# Full mode: both producer and consumer

CHRONICLE_MODE=full just run

# Producer only: accepts HTTP requests, publishes to channel

CHRONICLE_MODE=producer just run

# Consumer only: subscribes to channel, stores events

CHRONICLE_MODE=consumer just run

This lets you scale independently. Need more consumers to handle load? Spin up more consumer instances. Need geographic distribution? Run producers close to your users and consumers close to your database.

Here’s how the main entry point handles this:

// Start consumers if this endpoint is configured as a consumer

let consumer_pool = case config.is_consumer(cfg) {

False -> {

log.info("Producer mode: not starting consumers")

Error(Nil)

}

True -> {

case gateway.start_consumers(gateway_result.gateway, cfg.consumer_count, store) {

Ok(pool) -> {

log.info("Started " <> int.to_string(gateway.consumer_count(pool)) <> " consumers")

Ok(pool)

}

Error(msg) -> {

log.error("Failed to start consumers: " <> msg)

Error(Nil)

}

}

}

}

// Start HTTP server if this endpoint is configured as a producer

case config.is_producer(cfg) {

True -> start_http_server(ctx, cfg.port)

False -> log.info("Consumer mode: HTTP server not started")

}

The gateway even abstracts consumer lifecycle. When you call gateway.start_consumers(), you don’t know if you’re starting OTP actors or RabbitMQ subscriptions. You just get back a ConsumerPool handle.

Testing Independent Deployment

With RabbitMQ running via Docker Compose, you can test this for real:

# Terminal 1: Start RabbitMQ

just rabbit-up

# Terminal 2: Start producer (no consumers)

just transport=rabbitmq producer

# Terminal 3: Start consumer (no HTTP server)

just transport=rabbitmq consumer

# Terminal 4: Send events

just post

Events published in Terminal 2 get consumed in Terminal 3. The producer doesn’t know or care where the consumer is running.

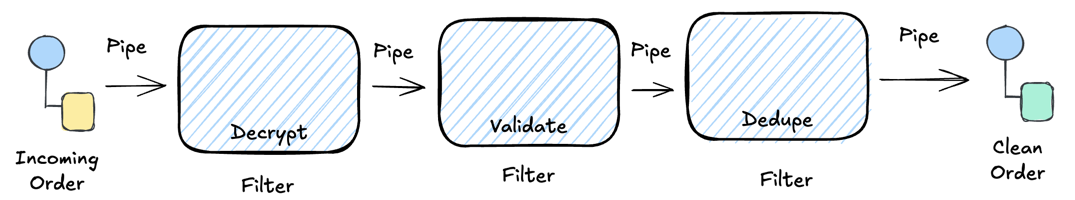

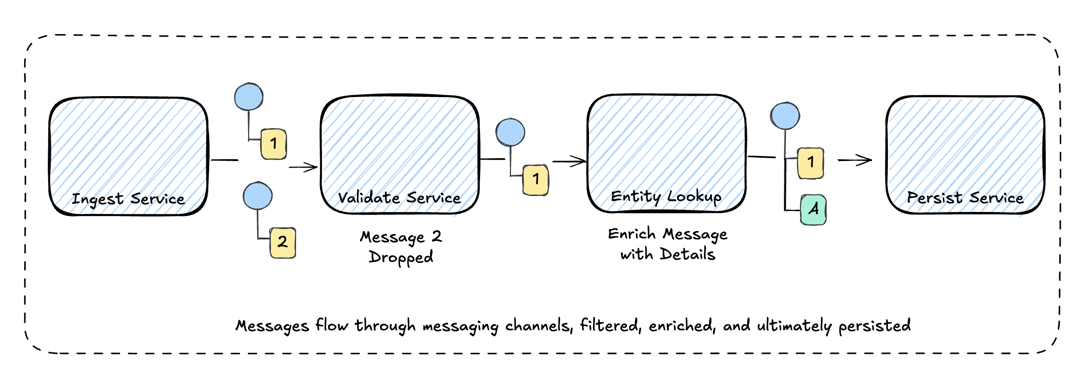

Pipes and Filters: Composable Processing

Now for my favorite pattern of the day. Pipes and Filters describes how to build processing pipelines from small, independent steps:

“Divide a larger processing task into a sequence of smaller, independent processing steps (Filters) that are connected by channels (Pipes).”

Think Unix pipes. Each filter does one thing. You chain them together for complex behavior.

Pipes and Filters: Messages flow through a sequence of processing steps

Pipes and Filters: Messages flow through a sequence of processing steps

In Chronicle, events flow through a processing pipeline before hitting the gateway:

/// A Filter transforms an event and returns a FilterResult

pub type Filter =

fn(AuditEvent) -> FilterResult

/// A Pipeline is an ordered list of filters

pub type Pipeline =

List(Filter)

/// Process an event through all filters in sequence

pub fn process(pipeline: Pipeline, event: AuditEvent) -> Result(AuditEvent, String) {

do_process(pipeline, event)

}

fn do_process(remaining: List(Filter), event: AuditEvent) -> Result(AuditEvent, String) {

case remaining {

[] -> Ok(event)

[filter, ..rest] -> {

case filter(event) {

Continue(transformed) -> do_process(rest, transformed)

Reject(reason) -> Error("Rejected: " <> reason)

Skip(reason) -> Error("Skipped: " <> reason)

}

}

}

}

Each filter can Continue (pass the event to the next filter), Reject (stop processing with an error), or Skip (silently drop the event).

Built-in Filters

Chronicle ships with several reusable filters:

Validation filters ensure data quality:

/// Validate that required fields are present and non-empty

pub fn validate_required() -> Filter {

fn(event: AuditEvent) {

case event.actor, event.action, event.resource_type {

"", _, _ -> Reject("actor is required")

_, "", _ -> Reject("action is required")

_, _, "" -> Reject("resource_type is required")

_, _, _ -> Continue(event)

}

}

}

Normalization filters clean up input:

/// Normalize actor to lowercase (for consistent lookups)

pub fn normalize_actor() -> Filter {

fn(event: AuditEvent) {

Continue(event.AuditEvent(..event, actor: string.lowercase(event.actor)))

}

}

Enrichment filters add metadata:

/// Add a correlation ID if not already present

pub fn add_correlation_id() -> Filter {

fn(event: AuditEvent) {

case event.correlation_id {

Some(_) -> Continue(event)

None -> {

let cid = uuid.v4_string()

Continue(event.AuditEvent(..event, correlation_id: Some(cid)))

}

}

}

}

Pipes and Filters at Any Scale

Here’s what makes Pipes and Filters so powerful: it’s a general abstraction that works at multiple scales.

In Chronicle, filters are just functions. We chain them with Gleam’s pipe operator:

/// Process an event through the ingestion pipeline

pub fn ingest(event: AuditEvent) -> Result(AuditEvent, String) {

Ok(event)

|> result.try(validate_required)

|> result.try(trim_fields)

|> result.try(normalize_actor)

|> result.try(add_correlation_id)

}

No special Pipeline type needed — just functions and result.try. If any filter returns Error, the chain stops.

But the same pattern applies at a distributed scale. Imagine each filter as a separate service:

Each service subscribes to a topic, processes the message, and publishes to the next topic. The “pipes” are now message queues. The “filters” are now microservices.

This is exactly how tools like Kafka Connect work. You define a pipeline of transformations:

- Source Connector reads from a system (database, API, file)

- Transforms filter, route, or enrich messages in flight

- Sink Connector writes to a destination (another database, SQS, Elasticsearch)

For example, you might:

- Subscribe to a Kafka topic of raw events, of which many different kinds of events are published

- Filter only on one specific event type

- Push into an SQS queue for downstream processing

The pattern is the same whether your filters are functions in a list or Docker containers behind a load balancer. That’s the beauty of good abstractions — they scale with your architecture.

In Chronicle, we’re keeping it simple with in-process filters. But if we needed to scale, we could extract each filter into its own consumer service, connected by RabbitMQ queues. The code would change, but the mental model stays the same.

Entity Enrichment (at Read Time)

Here’s where it gets interesting. Chronicle has an entity registry — a lookup table for enriching events with contextual metadata. But here’s the key insight: we enrich at read time, not write time.

Why? Because entity data changes. If you denormalize org:acme’s attributes into every event at ingestion, you’re stuck with stale data forever. When Acme Corp upgrades from “team” to “enterprise” tier, all their historical events still show “team”. That’s not what you want for reporting or analytics.

Instead, events store just the entity_key reference. When you read events back, Chronicle hydrates them with current entity data:

First, register an entity:

curl -X POST http://localhost:8080/entities \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{

"key": "org:acme",

"name": "Acme Corporation",

"attributes": {

"tier": "team",

"region": "us-west"

}

}'

Then reference it when creating events:

curl -X POST http://localhost:8080/events \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{

"actor": " Alice@ACME.COM ",

"action": "create",

"resource_type": "document",

"resource_id": "doc-123",

"entity_key": "org:acme"

}'

The event is stored with just the key — no entity data baked in. The ingestion pipeline still validates, trims, and normalizes, but doesn’t enrich.

When you retrieve events, Chronicle hydrates them:

/// Hydrate an event with entity data at read time

pub fn hydrate_event(event: AuditEvent, entity_store: EntityTable) -> AuditEvent {

case event.entity_key {

Some(key) -> {

case entity_store.get(entity_store, key) {

Ok(entity) -> {

let enriched_metadata =

event.metadata

|> dict.insert("entity_name", entity.name)

|> dict.merge(entity.attributes)

AuditEvent(..event, metadata: enriched_metadata)

}

Error(Nil) -> event // Entity not found, return as-is

}

}

None -> event

}

}

/// Get all events, hydrated with current entity data

pub fn get_events(store: EventStore, entity_store: EntityTable) -> List(AuditEvent) {

store.list_all(store)

|> list.map(fn(event) { hydrate_event(event, entity_store) })

}

The returned event is enriched with current entity data:

{

"id": "evt-uuid",

"actor": "alice@acme.com",

"action": "create",

"resource_type": "document",

"resource_id": "doc-123",

"correlation_id": "auto-generated-uuid",

"entity_key": "org:acme",

"metadata": {

"entity_name": "Acme Corporation",

"tier": "team",

"region": "us-west"

}

}

Now update the entity:

curl -X PUT http://localhost:8080/entities/org:acme \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{

"name": "Acme Corporation",

"attributes": {

"tier": "enterprise",

"region": "us-west"

}

}'

Fetch the same event again — it now shows the updated tier:

{

"metadata": {

"entity_name": "Acme Corporation",

"tier": "enterprise",

"region": "us-west"

}

}

This is like a database join at query time versus denormalizing at insert time. The entity_key is your foreign key; the entity registry is your lookup table.

Notice what the ingestion pipeline still handles:

- Actor was trimmed and lowercased (

" Alice@ACME.COM "→"alice@acme.com") - Correlation ID was auto-generated

- Validation ensured required fields are present

Write-time concerns stay in the pipeline. Read-time enrichment happens when you query.

Ingestion Pipeline

The ingestion pipeline handles write-time concerns only — validation, normalization, and metadata generation:

/// Ingestion pipeline: validate and normalize, but don't enrich

pub fn ingest(event: AuditEvent) -> Result(AuditEvent, String) {

Ok(event)

|> result.try(validate_required)

|> result.try(trim_fields)

|> result.try(normalize_actor)

|> result.try(add_correlation_id)

}

The router validates incoming events before storing:

// Process through the ingestion pipeline

case filters.ingest(raw_event) {

Ok(processed_event) -> {

// Store the clean event (with entity_key, not enriched data)

gateway.send_event(ctx.gateway, processed_event)

// ...

}

Error(reason) -> {

wisp.response(422)

|> wisp.json_body(json.to_string(

json.object([

#("error", json.string("validation_failed")),

#("reason", json.string(reason)),

])

))

}

}

Validation failures return HTTP 422 with a reason. No bad data sneaks through. Enrichment happens later, when events are read.

Putting It All Together

So how do all these patterns compose? Let’s trace a request through the system.

Chronicle uses Message Endpoints to define application roles. The Producer Endpoint accepts HTTP requests and publishes events, while Consumer Endpoints subscribe and persist to storage. The transport abstraction (our gateway) means the same endpoint code works whether messages flow through in-process OTP actors or a distributed RabbitMQ broker.

Here’s the flow:

- HTTP request arrives at the Producer Endpoint

- Ingestion Pipeline (Pipes and Filters) validates, normalizes, and adds correlation IDs

- Gateway receives the clean event — it doesn’t care if we’re using OTP or RabbitMQ

- Message Channel (hidden by the gateway) queues the event

- Consumer Endpoints pull from the channel and store in ETS

- Read requests hydrate events with current entity data from the Entity Registry

The patterns form layers:

| Layer | Pattern | Responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| Application | Message Endpoint | Define roles (producer vs consumer) |

| Processing | Pipes and Filters | Validate, transform, enrich |

| Transport | Gateway abstraction | Hide transport: OTP, RabbitMQ or others |

| Delivery | Point-to-Point Channel | Queue and deliver messages |

| Scaling | Competing Consumers | Parallel processing |

Each layer has a single job. Swap out the transport? Only the gateway changes. Add a new filter? The pipeline grows. Scale consumers? Spin up more instances. The patterns keep concerns cleanly separated.

The key insight: Endpoint roles and transport are orthogonal. You configure them independently:

# Full mode with OTP transport

CHRONICLE_MODE=full CHRONICLE_TRANSPORT=otp just run

# Producer-only with RabbitMQ transport

CHRONICLE_MODE=producer CHRONICLE_TRANSPORT=rabbitmq just run

# Consumer-only with RabbitMQ transport (separate process!)

CHRONICLE_MODE=consumer CHRONICLE_TRANSPORT=rabbitmq just run

Same code, different configurations, different deployment topologies.

Running Day 2 Chronicle

Ready to try it? The code is at github.com/jamescarr/chronicle on the day-2-eip branch.

git clone https://github.com/jamescarr/chronicle.git

cd chronicle

git checkout day-2-eip

# OTP mode (default)

just run

# RabbitMQ mode

just rabbit-up

just transport=rabbitmq run

Test the entity enrichment:

# Register an entity

curl -X POST localhost:8080/entities -H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"key":"tenant:acme","name":"Acme Corp","attributes":{"tier":"enterprise"}}'

# Create an event with entity reference

curl -X POST localhost:8080/events -H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"actor":"CEO@Acme.com","action":"export","resource_type":"report","resource_id":"q4","entity_key":"tenant:acme"}'

# See the enriched result

curl localhost:8080/events | jq

The Elephant in the Room: Data Consistency

Sharp-eyed readers might have noticed a problem. When we run the producer and consumers separately with RabbitMQ:

# Terminal 1: Producer (HTTP API, publishes to RabbitMQ)

just transport=rabbitmq producer

# Terminal 2: Multiple consumers (subscribe to RabbitMQ, store in ETS)

just transport=rabbitmq consumers 3

# Terminal 3: blast messages

just flood 10

Try querying the API for events:

curl localhost:8080/events | jq

# Returns: []

Empty! Where did our events go?

The producer’s ETS store is empty because it only publishes events — it doesn’t store them. The consumers have the data, but they don’t expose an HTTP API. We’ve successfully distributed our processing, but we’ve fragmented our data.

You can verify the events exist by inspecting each consumer’s ETS directly:

# See what consumer1 processed

just events-dump consumer1

# Compare with consumer2

just events-dump consumer2

# Each has different events! (Competing consumers pattern in action)

This is fine for demonstrating the patterns, but in production you’d want one of two approaches:

Shared Database: Replace ETS with PostgreSQL, Redis, or another shared store. All consumers write to the same place, and any node can query. This is the straightforward path and likely where we’ll take Chronicle in a future post.

Tenant-Based Routing: Route events to specific consumers based on tenant ID, region, or some other partition key. Each consumer “owns” a subset of the data. Queries route to the right consumer. This is more complex but scales horizontally — think Kafka partitions or sharded databases.

Both approaches involve routing — deciding where messages go based on their content. Which brings us to…

What’s Next: Day 3

Tomorrow we’ll tackle routing. Right now, all events flow through the same channel. But what if we want different event types to go to different destinations? What if security events need special handling? What if we want to partition by tenant?

We’ll implement Content-Based Router to route events based on their content, and Message Filter to selectively drop events that don’t match criteria. These patterns will let us solve the data consistency problem and add sophisticated event routing. Chronicle will start to feel like a real event processing system.

See you tomorrow! 🎄

This post is part of the Advent of Enterprise Integration Patterns series. Check out the introduction or follow along with the enterprise-integration-patterns tag.

Code for this series is available at github.com/jamescarr/chronicle. Today’s code: day-2-eip.