Welcome to Day 1 of the Advent of Enterprise Integration Patterns! Today we tackle the foundational question every distributed system must answer: how do systems share information? Can someone just call me!?

Chapter 2 of Enterprise Integration Patterns lays out four fundamental integration styles. Understanding these options and their trade-offs is essential before diving into the patterns themselves. Let’s examine each one, drawing from real-world experience, and then bootstrap Chronicle with our first pattern implementation.

The Four Integration Styles

Before microservices, before Kafka, before REST APIs, engineers were solving integration problems. The EIP authors identified four fundamental approaches that remain relevant today.

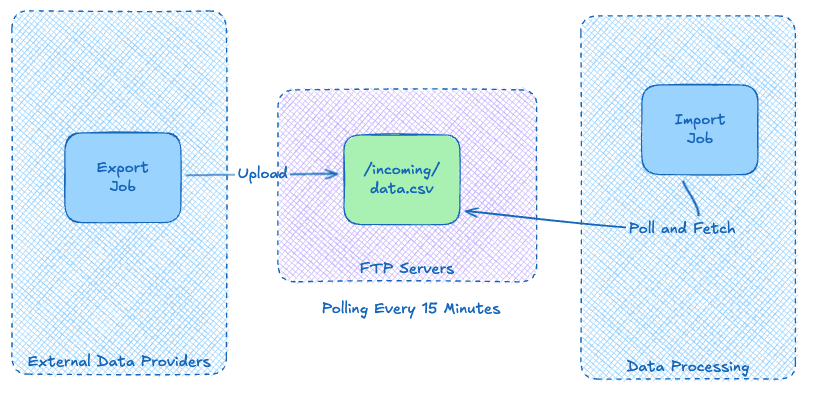

File Transfer

The oldest and simplest approach: one system writes a file, another reads it.

I saw this pattern extensively at Carfax, it’s a very general pattern. Data providers uploaded files to FTP servers, scheduled jobs detected new files, and data pipelines ingested them for persistence and display on vehicle history reports. It worked, but the limitations became apparent quickly.

// Producer: Export data to file system

pub fn export_vehicle_data(records: List(VehicleRecord)) -> Result(Nil, FileError) {

let timestamp = birl.utc_now() |> birl.to_iso8601

let filename = "vehicle_data_" <> timestamp <> ".csv"

// Convert records to CSV lines

let csv_content =

records

|> list.map(fn(r) { r.vin <> "," <> r.event <> "," <> r.date })

|> string.join("\n")

// Write to shared directory (or FTP mount)

simplifile.write("/outgoing/" <> filename, csv_content)

}

// Consumer: Poll for new files on a timer

pub fn start_file_watcher() {

// Check every 15 minutes

let interval_ms = 15 * 60 * 1000

process.start(fn() {

loop_forever(fn() {

case simplifile.read_directory("/incoming") {

Ok(files) -> {

files

|> list.filter(fn(f) { string.ends_with(f, ".csv") })

|> list.filter(fn(f) { !is_processed(f) })

|> list.each(fn(filename) {

let content = simplifile.read("/incoming/" <> filename)

process_vehicle_data(content)

mark_as_processed(filename)

})

}

Error(_) -> Nil

}

process.sleep(interval_ms)

})

})

}

Pros:

- Simple to implement

- Works across any technology stack

- Natural audit trail (the files themselves)

- Good for batch processing

Cons:

- High latency (batch windows)

- No standard format (CSV? XML? JSON? Fixed-width?)

- Tight coupling to file locations and naming conventions

- Error handling is painful (partial files, corrupt data, duplicate processing)

At Carfax, data that should have been available in minutes sometimes took days because everything was tied to batch schedules. When a file failed to process, debugging meant digging through logs across multiple systems.

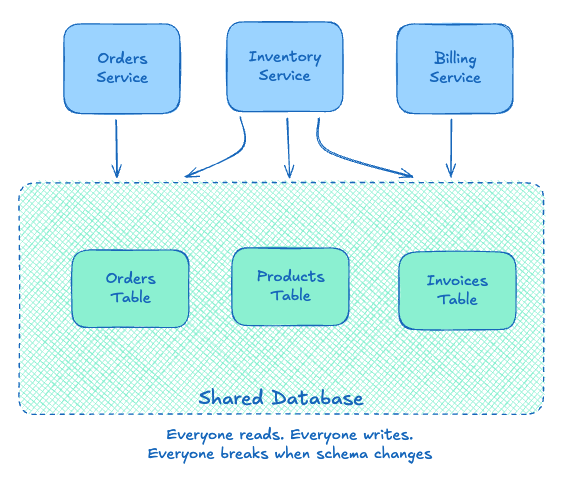

Shared Database

Multiple applications read and write to the same database. Sounds elegant in theory.

// Orders Service: writes to shared database

pub fn create_order(

db: Connection,

customer_id: String,

items: List(OrderItem),

) -> Result(String, DbError) {

use tx <- db.transaction(db)

// Insert order into our table

let assert Ok(order_id) = db.execute(tx,

"INSERT INTO orders (customer_id, status) VALUES ($1, 'pending') RETURNING id",

[customer_id]

)

// Directly updating inventory table owned by another team!

// This crosses service boundaries at the data layer

list.each(items, fn(item) {

db.execute(tx,

"UPDATE products SET stock = stock - $1 WHERE id = $2",

[item.quantity, item.product_id]

)

})

Ok(order_id)

}

// Billing Service: reads from the same tables

pub fn generate_invoice(db: Connection, order_id: String) -> Result(Invoice, DbError) {

// Tight coupling: we know Orders team's schema intimately

// What happens when they rename a column? We break.

let assert Ok(rows) = db.execute(db,

"SELECT o.*, p.price, p.name

FROM orders o

JOIN order_items oi ON oi.order_id = o.id

JOIN products p ON p.id = oi.product_id

WHERE o.id = $1",

[order_id]

)

// If Orders team changes their schema, this code breaks

create_invoice_from_rows(rows)

}

Pros:

- Immediate consistency

- Simple to query across “integrated” data

- One source of truth

- Transactions across operations

Cons:

- Tight coupling (schema changes break everyone)

- Performance bottlenecks (one database serves all)

- Security challenges (who can access what?)

- Technology lock-in

I’ve seen shared databases work for small teams with high trust. They become a nightmare at scale. Every schema migration becomes a cross-team negotiation. The database becomes a bottleneck. And inevitably, someone writes a query that brings down production for everyone.

The fundamental problem? You’ve coupled systems at the data level, the most intimate coupling possible. When System A changes its table structure, Systems B, C, and D need to adapt or break. For more on this, see Don’t Share Databases Between Services.

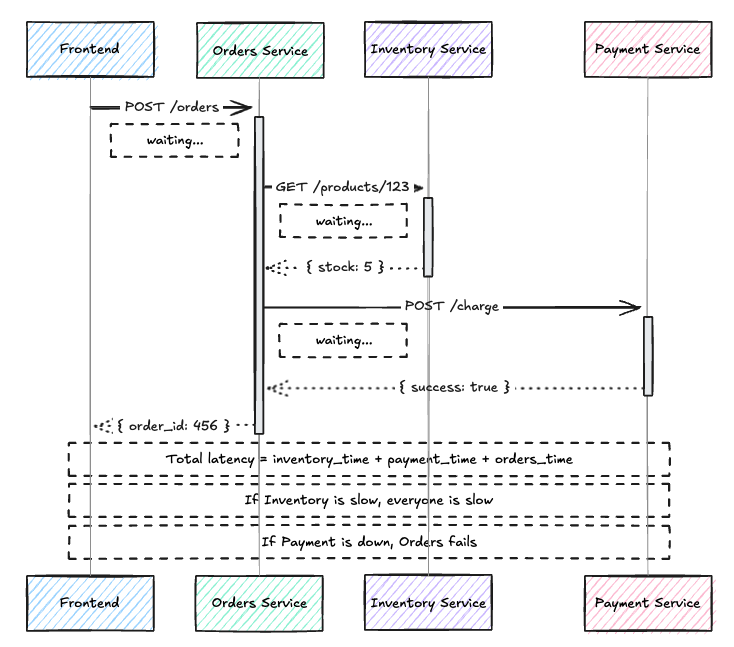

Remote Procedure Invocation (RPC)

One system calls another directly. REST APIs, gRPC, SOAP, GraphQL… all variations of this theme.

pub fn create_order(

customer_id: String,

product_id: String,

quantity: Int,

) -> Result(Order, OrderError) {

// Synchronous call: we block waiting for Inventory to respond

let inventory_url = "http://inventory-service/products/" <> product_id

use response <- result.try(

httpc.send(request.get(inventory_url))

|> result.map_error(fn(_) { ServiceUnavailable("Inventory") })

)

use stock <- result.try(case response.status {

200 -> decode_stock(response.body)

_ -> Error(ServiceUnavailable("Inventory returned " <> int.to_string(response.status)))

})

use _ <- result.try(case stock >= quantity {

True -> Ok(Nil)

False -> Error(InsufficientStock)

})

// Another synchronous call to Payment

// Total latency = inventory_time + payment_time + our_time

use payment_response <- result.try(

httpc.send(

request.post("http://payment-service/charge")

|> request.set_body(json.to_string(

json.object([

#("customer_id", json.string(customer_id)),

#("amount", json.int(price * quantity)),

])

))

)

|> result.map_error(fn(_) { ServiceUnavailable("Payment") })

)

// If either service is slow, we're slow

// If either service is down, we fail

case payment_response.status {

200 -> save_order(customer_id, product_id, quantity)

_ -> Error(PaymentFailed)

}

}

Pros:

- Real-time interaction

- Clear contracts (API specs, protobuf definitions)

- Request/response semantics

- Widely understood

Cons:

- Temporal coupling (caller waits for response)

- Cascade failures (if the service is down, you’re down)

- Tight availability requirements

- Scaling challenges (every caller adds load)

RPC is the default for many teams because it’s intuitive. You want data, you ask for it. But as systems grow, the web of dependencies becomes fragile. Service A calls Service B, which calls Service C. If C is slow, A is slow. If C is down, A might be down too.

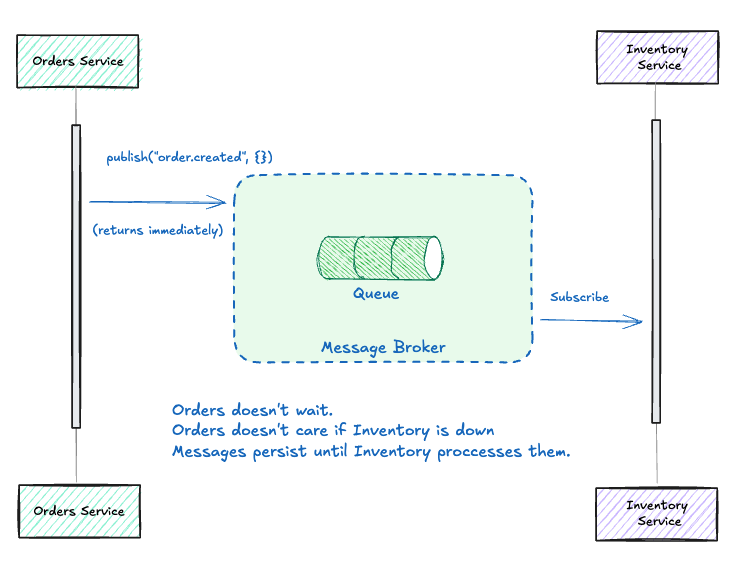

Messaging

Systems communicate by sending messages through channels. The sender doesn’t wait for a response; it trusts the message will be delivered and processed.

// Orders Service: publishes events, doesn't wait

pub fn create_order(

channel: Subject(ChannelMessage),

customer_id: String,

product_id: String,

quantity: Int,

) -> Order {

// Save to our own database first

let order = save_order(customer_id, product_id, quantity)

// Publish event and return immediately

// We don't wait for anyone to process it

let event = OrderCreated(

order_id: order.id,

product_id: product_id,

quantity: quantity,

)

// Fire and forget - this returns immediately

actor.send(channel, Send(event))

// Return to caller right away

// Inventory will process this whenever it's ready

order

}

// Inventory Service: consumes at its own pace

pub fn start_inventory_consumer(channel: Subject(ChannelMessage)) {

actor.new(Nil)

|> actor.on_message(fn(state, _msg) {

// Try to receive from the channel

case channel.receive(channel, 1000) {

Ok(OrderCreated(product_id, quantity, ..)) -> {

// Process at our own pace

// If we're slow or crash, messages wait in the queue

reserve_stock(product_id, quantity)

actor.continue(state)

}

Error(Nil) -> {

// No messages right now, keep polling

actor.continue(state)

}

}

})

|> actor.start

}

// The key difference: Orders doesn't know or care if Inventory is running

// Messages persist in the channel until someone processes them

Pros:

- Temporal decoupling (sender and receiver don’t need to be available simultaneously)

- Location transparency (don’t care where the receiver is)

- Scalability (add more consumers to handle load)

- Reliability (messages persist until processed)

Cons:

- Eventual consistency (not immediately reflected)

- Complexity (need infrastructure: queues, brokers)

- Debugging challenges (messages flow asynchronously)

- Learning curve (different mental model)

This is where Enterprise Integration Patterns lives, and where Chronicle will live too.

Why Messaging for Chronicle?

Audit logging has specific requirements that make messaging the natural fit.

First, we can’t lose events. If a user performs an action, it must be recorded. Messaging systems provide durability and guaranteed delivery.

We also need to scale independently. The audit ingestion rate shouldn’t be coupled to the query rate. With messaging, we can scale producers and consumers separately.

Multiple consumers need the same data. Audit events might go to Elasticsearch for search, DynamoDB for point queries, S3 for archival, and a webhook for real-time alerts. Messaging makes this fan-out natural.

Finally, producers shouldn’t wait. When a user clicks “delete,” they shouldn’t wait for the audit system to write to three databases. Fire the message and move on.

Now let’s build it.

Bootstrapping Chronicle

Chronicle is our audit logging system. Today we implement the core: an HTTP API that accepts audit events and processes them through a Point-to-Point Channel.

The full code is available at github.com/jamescarr/chronicle. Today’s implementation has two tags: day-1-one-consumer for the simple version and day-1-many-consumers for competing consumers.

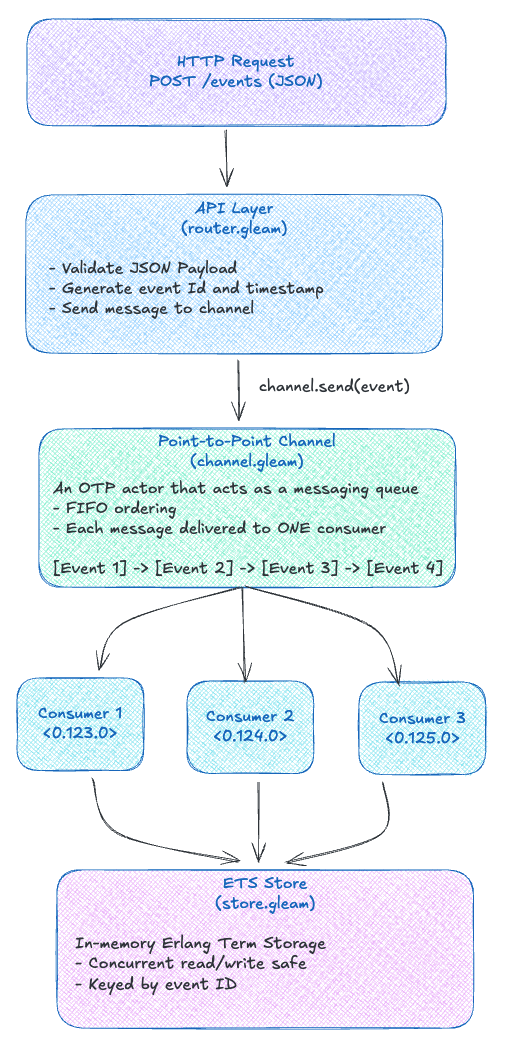

The Architecture

The Message: Our Audit Event

In EIP terminology, a Message is the atomic unit of data transferred through a messaging system. For Chronicle, that’s an audit event (view source):

/// An audit event capturing who did what to which resource

pub type AuditEvent {

AuditEvent(

id: String,

actor: String,

action: String,

resource_type: String,

resource_id: String,

timestamp: String,

)

}

Simple and focused. Who (actor) did what (action) to which thing (resource_type/resource_id) and when (timestamp). The id is generated server-side for deduplication and tracking.

The Point-to-Point Channel

A Point-to-Point Channel ensures that exactly one consumer processes each message. This is fundamental for audit logging because we don’t want duplicate records.

In Gleam, we implement this as an OTP actor. If you’re not familiar with actors, think of them as lightweight processes with their own mailbox. They receive messages, process them, and can send messages to other actors. See Gleam’s OTP documentation for more.

Here’s our channel’s message types (view source):

/// Messages the channel can receive

pub type ChannelMessage {

Send(AuditEvent)

Receive(Subject(Result(AuditEvent, Nil)))

}

/// Channel state is just a queue of events

pub type ChannelState {

ChannelState(queue: Queue(AuditEvent))

}

The channel maintains a queue of events. When it receives a Send, it enqueues the event. When it receives a Receive, it dequeues and replies.

fn handle_message(state: ChannelState, message: ChannelMessage)

-> actor.Next(ChannelState, ChannelMessage) {

case message {

Send(event) -> {

let new_queue = queue.push_back(state.queue, event)

actor.continue(ChannelState(queue: new_queue))

}

Receive(reply_to) -> {

case queue.pop_front(state.queue) {

Ok(#(event, remaining)) -> {

actor.send(reply_to, Ok(event))

actor.continue(ChannelState(queue: remaining))

}

Error(Nil) -> {

actor.send(reply_to, Error(Nil))

actor.continue(state)

}

}

}

}

}

This is Point-to-Point in its purest form. Only one consumer gets each message. No broadcasting, no fanout, just reliable delivery to a single processor.

Why OTP?

You might wonder why we’re implementing our own channel when we could use RabbitMQ or SQS.

For Day 1, we’re building with baked-in solutions to understand the patterns at their core. The BEAM (Erlang VM) gives us the primitives to implement these patterns directly. Processes are lightweight (2KB each) and isolated. Message passing is built into the runtime. Supervision trees handle failures gracefully. ETS provides concurrent in-memory storage.

This isn’t production infrastructure. It’s a learning tool. But here’s the key insight: the patterns are the same regardless of implementation.

| Chronicle (OTP) | RabbitMQ | SQS | Kafka |

|---|---|---|---|

| Channel actor | Queue | Queue | Topic + Consumer Group |

channel.send() | basic.publish | SendMessage | producer.send() |

channel.receive() | basic.consume | ReceiveMessage | consumer.poll() |

| Consumer actor | Consumer worker | Lambda/Worker | Consumer instance |

The vocabulary transfers. Once you understand Point-to-Point Channels in Chronicle, you’ll recognize them everywhere.

Single Consumer: The Simple Case

Our first implementation uses a single consumer (view source). It works, but what happens under load?

INFO [<0.123.0>] [consumer-1] Processing event abc-123 - create

INFO [<0.123.0>] [consumer-1] Processing event def-456 - update

INFO [<0.123.0>] [consumer-1] Processing event ghi-789 - delete

One consumer handles everything. If processing is slow, messages queue up. If the consumer crashes, processing stops.

This classic video explains how event-driven architecture and messaging systems address these challenges:

Competing Consumers: Scaling Out

The Competing Consumers pattern solves the single-consumer bottleneck. Multiple consumers pull from the same channel, racing to grab each message:

/// Start multiple competing consumers

pub fn start_pool(

count: Int,

ch: Subject(ChannelMessage),

st: Table,

) -> List(Subject(ConsumerMessage)) {

list.range(1, count)

|> list.filter_map(fn(i) {

case start_named("consumer-" <> int.to_string(i), ch, st) {

Ok(started) -> Ok(started.data)

Error(_) -> Error(Nil)

}

})

}

Now three consumers compete for work:

INFO [<0.123.0>] [consumer-1] Processing abc-123 - create

INFO [<0.124.0>] [consumer-2] Processing def-456 - update

INFO [<0.125.0>] [consumer-3] Processing ghi-789 - delete

INFO [<0.123.0>] [consumer-1] Processing jkl-012 - archive

INFO [<0.124.0>] [consumer-2] Processing mno-345 - export

Load is distributed. If one consumer is slow, others pick up the slack. If one crashes, the others continue.

The trade-offs are worth knowing. You get horizontal scalability, fault tolerance, and better resource utilization. But message ordering isn’t guaranteed (consumer-2 might finish before consumer-1), debugging becomes more complex (which consumer processed what?), and you need idempotent handlers since the same message might be delivered twice during failures.

For audit logging, ordering within a single event stream matters less than reliability. We’ll address ordering in later days with patterns like Resequencer.

The Persistence Layer: ETS

We’re using ETS (Erlang Term Storage) as our persistence layer (view source). ETS is an in-memory key-value store built into the BEAM:

/// Initialize the ETS table

pub fn init() -> Table {

create_table()

}

/// Insert an event

pub fn insert(table: Table, event: AuditEvent) -> Bool {

insert_event(table, event.id, event)

}

/// List all events

pub fn list_all(table: Table) -> List(AuditEvent) {

list_all_events(table)

}

ETS is fast and concurrent but volatile. When the process restarts, data is gone. This is fine for Day 1 since we’re focusing on the messaging patterns, not production durability.

In Day 2, we’ll introduce Message Endpoints and the Ports and Adapters architecture. This will let us swap ETS for Elasticsearch, DynamoDB, or any other backend without changing our core logic.

Running Chronicle

Want to try it yourself? Clone the repo:

git clone https://github.com/jamescarr/chronicle.git

cd chronicle

git checkout day-1-many-consumers # or day-1-one-consumer for the simpler version

# Install dependencies

just deps

# Build the project

just build

# Start the server

just run

Then in another terminal:

# Send a random audit event

just ingest

# Send many events to see competing consumers in action

just flood 20

# View all stored events

just list-events

Watch the logs to see which consumer processes each event!

What We Covered

Today we explored the four integration styles from EIP Chapter 2 and why messaging fits audit logging’s requirements. We implemented Point-to-Point Channels for reliable single-delivery and added Competing Consumers for scalable processing. OTP actors served as our implementation vehicle, with ETS providing a simple (temporary) persistence layer.

Coming Tomorrow: Day 2

With our basic service running, we’ll deepen our understanding of the core abstractions. What makes a Message Channel more than just a function call? What’s a Message Endpoint and why does it matter? How do we properly separate concerns using Ports and Adapters? How do Pipes and Filters give us composable processing?

We’ll refactor Chronicle to support multiple output adapters, setting the stage for adding Elasticsearch, DynamoDB, and other backends. The BEAM’s actor model maps naturally to these concepts, and we’ll see how.

See you tomorrow! 🎄

This post is part of the Advent of Enterprise Integration Patterns series. Check out the introduction or follow along with the enterprise-integration-patterns tag.

Code for this series is available at github.com/jamescarr/chronicle. Today’s code: day-1-one-consumer and day-1-many-consumers.